Grumbling Fur make me want to take drugs. And I don’t mean drugs like a few puffs on a spliff before bedtime or on a lazy Saturday afternoon, or a cheeky dabble at a rave to keep the energy flowing – I mean proper, don’t-eat-for-18-hours-beforehand, make-sure-you’ve-got-a-couple-of-good-people-around-you, psychically prepared voyaging, preferably on a warm and sunny but slightly overcast afternoon in a field somewhere in the West Country, or in a friend’s house cluttered to the rafters with fascinating and peculiar objects. On their second album Glynnaestra, the duo of Alexander Tucker and Daniel O’Sullivan conjure up a wonderfully evocative and distinctly British kitchen sink psychedelia, an intimate shared space where the whistle of a kettle and the clatter of pots and pans can sit seamlessly alongside heavily reverbed 80s pop synths, expansive rural landscapes, delectably ludicrous choruses and invocations to imaginary deities.

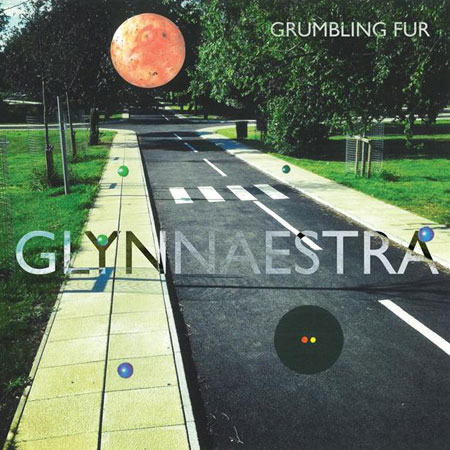

As with its cover artwork, which depicts bubble-like planetary bodies drifting above a quiet suburban street, it’s this juxtaposition of the magical and the ordinary – the discovery of the profound in the deeply mundane, a hallmark of psychedelic experience – that makes Glynnaestra such a continually compelling listen. Each time I return to it I become aware of some new facet I’d not noticed before. Even its most pop-friendly tracks teem with near-imperceptible background detail, evoking the sustained suspicion that there’s something altogether more uncanny going on just beneath the surface of conscious awareness.

So beneath every wonderfully infectious chorus – and there are plenty of them here, from the colossally silly ‘The Ballad Of Roy Batty’ (of which more later) and the anthemic synth-pop of ‘Dancing Light’ to ‘Clear Path’s meditative, acidic folk – rhythms are allowed to tumble and slip in and out of phase with one another, while synthetic sounds whip like wind or hang low and foglike in the atmosphere. Meanwhile, the usual din of the surrounding world goes on undisturbed, even as the context it’s experienced within becomes more expansive and bizarre than everyday life. ‘The Hound’ finds the duo playing barista, stirring up a chorus of kettles into a steamy interlude, while the percussive thrum and buzz of ‘Alapana Blaze’ sounds tapped out on household implements and wind chimes.

The album toys with the disconnect between these varied sonic sensations, feeling like a playful space in which any idea can be raised and explored. Indeed, one of its most pleasurable characteristics is the duo’s unwillingness to separate out the more straightforward, songwriting aspects of what they do from their experiments with location recordings, sound collage and jagged synthesiser noise; as far as Tucker and O’Sullivan are concerned, they’re all part and parcel of the same sustained sonic trip. So the album opens, as all trips do, in an abrupt rush of overwhelming sensory input – ‘Ascatudaea’, all acidic synthesiser warble and chanted incantations – that’s strong enough to nearly knock you off your feet, before those sensations swiftly stabilise (but with little drop in intensity) into the towering, reverb-drenched pop chug of ‘Protogenesis’. It’s only several tracks later that the barrage of colour and intense imagery lets up, with the album catching its breath before launching into a contemplative, exploratory middle section – including the title track, named after a goddess the duo dreamed into existence, a brief, limpid pool of chorus-drenched guitar, violin and wordless sung vocals.

The way these varying facets – grinding abrasion versus catchy songwriting, environmental noise versus synthetic sound – are woven into one another makes Glynnaestra feel intriguingly contradictory. It’s at once epic in scope and disarmingly intimate, a trick reminiscent of later period (‘moon music’) Coil, a duo similarly skilled at channeling their very personal musical explorations into pieces that seemed to contain within themselves whole other worlds. (Notably, when the Quietus’ Luke Turner met up with Grumbling Fur recently to discuss the making of the album, they did so at a house in North London owned by Ian Johnstone, partner of Coil’s late Jhonn Balance.) The duo’s presence on the upcoming compilation album from The Outer Church still further highlights their presence among a growing and vibrant community of British musicians inspired by and furthering Coil’s voyages into folk forms and esoteric, haunted electronic music.

Beyond the distinctly lysergic twist to the music, the other aspect of Glynnaestra that stands out as particularly hallucinogenic in tone is its lyrical content, and its ability to wring almost cosmic significance from the most seemingly mundane of utterances. That’s felt especially during the album’s first third, where lines are repeated, mantra-like, until they expand to fill the music’s entire psychic space. On ‘Protogenesis’, shrouded in ripples of purple tinted synth that drift through the air like plumes of smoke, the duo half-chant, half-sing a single phrase across five minutes: "I saw you stand up and take eight steps across the floor". It’s a classically tripped-out observation, a simple action transferred into a thought loop which starts tugging away at your consciousness; in the context, the ‘eight’ begins to acquire particular resonance, but it’s impossible to figure out quite why. Similarly, I’m not sure if anyone but Grumbling Fur would be able to (or even think to) take Rutger Hauer’s classic soliloquy from Blade Runner ("I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe / Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion") and, through reverb and repetition, billow it outwards into ‘The Ballad Of Roy Batty’, which sounds as though it’s being sung from the stands of a stadium by thousands of people. It’s one of the album’s finest moments, somehow both serious and intensely, endearingly daft.

Glynnaestra‘s trip-like narrative arc – an explosion of an opener that drags you roughly into its world, a period of intense colour and heightened audiovisual sensation, followed by a cosy and meandering plateau – ends, inevitably, in an uneasy drift back downwards. The final two tracks are deep, contented sighs of relief, like lying backwards to examine the gradually diminishing ripples still pulsing through the clouds. But they’re flecked with the slightest tints of dissonance and uncertainty; the incidental sounds that flicker around the edges of perception in closer ‘His Moody Face’ feel akin to catching a glimpse of something unfathomably weird in your peripheral vision, only for it to vanish when you turn to look at it head-on. Which, in fact, is quite the opposite of what could be said for this excellent, playful and moving album as a whole: the closer you examine Glynnaestra, the deeper and stranger the rabbit hole goes.