It’s not remembered much, but in the early eighties Bauhaus were one of the bands signed in the USA by A&M Records as part of a surprisingly vibrant effort from that label when it came to any number of then-new UK acts. Then again, signing the Police and seeing them become superstars probably didn’t hurt, so there was a reason everyone from the Human League to Squeeze to Simple Minds to Joe Jackson found an American home there. Bauhaus never broke through, though, but by the time its various members had found Stateside success on their own in the late eighties, whether via Love and Rockets or Peter Murphy’s solo career, it meant inevitable re-releases — which means my first memory of Burning From The Inside, the final of the four studio albums that marked the band’s original run, was of a staggered, divided photo of a brightly lit but still ominous, wintry landscape encased in an American A&M-logo-marked CD longbox. Not perhaps what the group originally figured when it came to visual impact.

The thing about Burning From The Inside, turning thirty years old this month, is that there is no one thing — it’s an album title that lives up to itself, a sound of a tight unit fragmenting, where the centre stopped holding. One factor was uncontrollable: Murphy ended up suffering a bout of pneumonia that required extensive care at the time of the album’s recording, meaning both his performances and overall input were drastically reduced. The impact played out in various ways: the album’s lead-off track and one single, ‘She’s In Parties’, is disruptive enough to start with, Daniel Ash’s guitar playing one of his darkest, extreme blasts and smears, violent and queasily choppy. But the promotional video for the song tries to present the band as a unit even while Murphy gets in plenty of the glamour shots while the rest of the group sometimes literally stand around doing nothing. At one point the camera cuts away to show David J, Ash and Kevin Haskins doing a kind of kid’s game in the background. It all may be thoroughly intentional, but it’s hard not to read things as shifting rapidly. Before the album had even been released, the group made the decision to break-up following two last London shows a few weeks beforehand, leaving Burning behind as one last full-length sprawl of sound as an unintentional shroud.

But at the same time it’s such a compelling sprawl at its best, a case for fragmentation as beauty, where an alternate band path where the group never broke up would have it seen more as a new, rich chapter in an already varied act’s still unfolding history, taking the sense of multiple impulses that had played out on earlier full-lengths and singles and finding even more directions to explore. J’s particular fascination with the doom-heavy crawl of classic Jamaican dub production from the seventies was always evident from the start of the band — there’s a reason why ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ could have been one hell of a King Tubby production, going further in the course of ten minutes what the Clash never quite achieved throughout their own existence. The world of film and that powerful, fluid but anchoring bass recombine again on ‘She’s In Parties’, the lyrics serving an extended cinematic metaphor rather than a specific tribute, with the extended coda playing with every trick in the book — backwards guitar, melodica, deep as hell echo, fragmented snippets of singing. It’s no rewrite, but its own vibrant, darkly playful construction. It also helps underscore the no-less-compelling work of Haskins as a drummer, as keen to rework his straightforward performances through production as to blast away, a further indication of how involved he was in the overall sound and composition as much as the rest of the band.

As for Ash’s musicianship, the delicate precision he’d started unveiling on acoustic guitar a couple of albums beforehand started coming completely to the fore. ‘King Volcano’, which could almost be Dead Can Dance suddenly emerging out of nowhere were it not for Murphy’s unmistakable voice leading a sea shanty singalong, rotates around such a sweet, still alien guitar part while Haskins’s percussion seems even more like something from a long past century, future shock transformed into ghosts emerging into a new light. If you played it at Mumford and Sons or the Lumineers they wouldn’t get it — then again, they don’t deserve to. But the surprises and twists continue to emerge: one song, ‘Wasp’, is named after a synthesizer and barely lasts half a minute of a redone wisp of a melody; another, ‘Honeymoon Croon’, lets Haskins fully bust out the rolling glam-rock beat that he and so many other contemporaries used in the early eighties, not unexpected from them but rarely sounding so pummelling.

‘Antonin Artaud’ struts, twists and settles into a lyrical coda of “Those Indians wank on his bones,” which might be enough to make most go “Oh please” and tune out. Then again, Artaud himself might well sympathize with such a choice of words — and when the final minute and a half begins, a tight as hell tempo and arrangement shift on the part of the band that gets crazier and more intense as it goes, you suddenly realize that the epic roar of Drive Like Jehu (or just about any band on the similarly San Diego-based Gravity label) a decade later had deep roots indeed. Allegedly Bauhaus did a version of this song live around this time that went on for something like half an hour — and rather than being surprising it still almost seems too short. As it happens, though, the longest song on the album, the title track, is indeed just as long as ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’, only with an opposite feeling, like the sense of an experiment finally concluded. In place of the nervous, quick pace and slow ratcheting up of musical and lyrical tension on that debut, ‘Burning from the Inside’ starts only with Ash’s electric guitar in a steady loop of a riff, Murphy lyric revolving around a key line, “And now I don’t see you anymore.” When J and Haskins step into the arrangement at various points, it’s a stop-start chug, a kind of forcing a way through a song via staccato moments.

This sense of conclusion and other routes can be heard in the full emergence of J and Ash both as lead vocalists — the latter already had a few releases out with the Tones On Tail name — as Murphy’s illness meant time to work on their own and, quite literally, more songs to sing, in whole or in part. Whatever ill feelings that might have caused in terms of a larger group effort, their showcase moments are just that, and their two key load vocals capture them to a T. J’s ‘Who Killed Mr. Moonlight’ locks into the sense of a cinematic 1940s dark bar room jazz and hushed folk music that defined much of his later work, piano and distorted organ forming the lead instrument, Ash’s saxophone adding even more twisted sorrow to already crushed lyrics: “All our dreams are melted down… all our stories burnt… someone shot nostalgia in the back.” When J. plaintively sings towards the end of the song “Extracting wasps from stings in flight,” the arresting image is a simple reversal but feels all the more loaded.

As for Ash, he fully goes to town with a fragile, piercing beauty on the tune immediately following ‘Who Killed Mr. Moonlight’, ‘Slice of Life’, the T. Rex connection that the band had from its days of covering ‘Telegram Sam’ suddenly taking on a new life. But this was Bolan if he had been a slinky purr underpinning quick piercing anger rather than mutating into a strutting star machine, Ash initially singing over and again “What’s the difference” with a feeling of calm resignation backed by his own wordless sung sighs. When the chorus kicks in, swiftly but clearly repeated, you can almost hear him tear across the guitar strings with his fingers more than simply play. He then concludes an extended break on the chorus with the call “And the problem expands inside your HEAD!,” a blistering accusation potentially directed both outwardly and internally. So much of what not only Tones on Tail but also Love and Rockets would later extrapolate musically fully came to the fore here, on songs like ‘Real Life’, ‘An American Dream’ and more, but here it sounds like it’s bursting out even while leaving a gentle, calm touch.

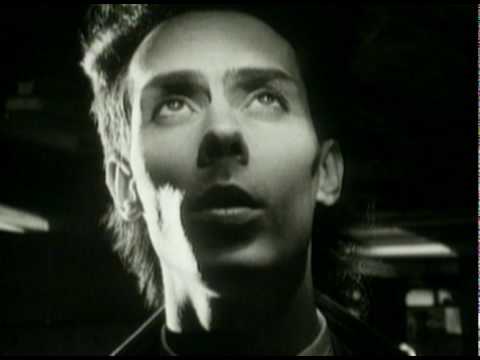

At the same time, when Murphy is the one singing lead over these musical combinations, the results suggest other ways forward that might have happened but simply couldn’t after this. ‘Kingdom’s Coming’ has another stellar, sweet Ash acoustic start, dramatic initially then suddenly flowing, while J’s piano adds to the arrangement, a ruined hint of a sonata. Following a clearly heard sigh that sounds completely resigned rather than romantic, Murphy sounds distant, literally looking heavenward perhaps as the title is delivered, then suddenly dragged and focused back into the final thirty seconds, broodily pronouncing as the others whisper/sing around him, a literalized opposition that might not actually be conflict but doesn’t seem like love.

Yet for all the twists and turns there’s still ‘Hope’. Literally: the last song on the album, and for nearly a decade and a half the last song Bauhaus ever did in most of the public eye. If ‘Hope’ had actually been the end of the Bauhaus story then that might have been a little happier for all concerned, even if that meant never seeing either of the two reunion phases or enjoying the half-completed clutch of tracks that made up the band’s actual last album Go Away White in 2008. (‘Endless Summer Of The Damned’, at the least, is a keeper from that one.) But ‘Hope’ would have been a real valediction and hail-and-farewell, if not necessarily on the band’s full terms.

With Murphy disappearing in echoed expulsions of words on the title track right before it, ‘Hope’ is again an Ash number in many ways, but different yet again from the earlier efforts, sweet guitar that could have been courtesy of the Byrds or Gram Parsons almost, J’s apparently fretless bass sounded similarly yearning, like throwing open a window to escape from everything gone before. The only words to the song, repeated several times, lock into that feeling perfectly — “Cause your mornings will be brighter/Break the line, tear up rules/Make the most of a million times no” — and they’re sung by several voices at once, no actual lead vocal as such. It’s a pep-up-your-spirits number after trawling through depths that somehow avoids treacle, it’s the least obvious thing one might think of when the name Bauhaus is invoked, and it’s precisely that fact that makes it the most appropriate way for such a band, always bigger than its stereotype, to step away.