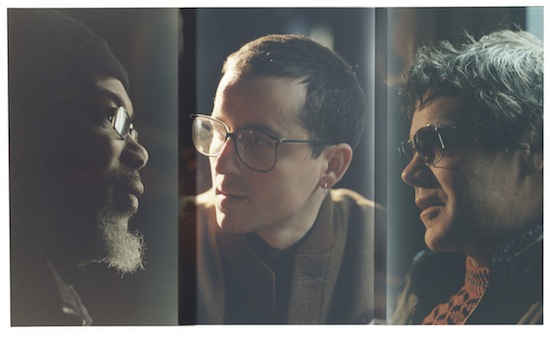

Seated in the back of a Soho basement, we find three quarters of About Group already deep in conversation. They’ve been working together, along with Charles Hayward of This Heat – unfortunately absent on this occasion – since 2009’s About, and between them, Alexis Taylor, John Coxon and Pat Thomas have some of the deepest insights into the British improv and indie scenes going. The group’s third album, Between The Walls, is out next week and it sees the band cutting looser than ever, on largely improvised tracks based around Alexis Taylor’s skeletal yet classic songwriting.

Thomas has played with the likes of Derek Bailey and Tony Oxley, while Coxon’s work with Spring Heel Jack and behind the scenes involvement with Spiritualized have incorporated free-jazz theory into an often more accessible and unusual context. Meanwhile Alexis Taylor, as frontman for Hot Chip, has been an integral part of the post-millennial electronic indie scene, seamlessly integrating catchy hooks and direct pop songwriting into an often infectiously danceable framework. About Group, however, is a wholly separate entity, and by now is unlike anything any of them have done before.

Initially brought together back in 2009 to record the totally improvised About for John Coxon’s own Treader label (alongside sessions by the likes of Wadada Leo Smith, Evan Parker and Jason Pierce), the quartet have since further developed into a wholly unique project. Alexis Taylor’s often stark solo songwriting in this new form – likewise documented on his 2008 solo album Rubbed Out, also released on Treader – was debuted live during a show in 2009 when the singer launched mid-improvisation into a song previously unrehearsed by the group. In amongst the wild and krautish improv of the group, the soulful songs instantly added a dramatic counterpoint to proceedings, something further explored on their second album, and first under the About Group name, Start & Complete.

Between The Walls shows a maturing quartet, increasingly unified as improvisers, in touch with Taylor’s songwriting and widening their sonic palette. The resultant album is the most dynamic yet from the group, at times harsher and more rollicking and unpredictable than their debut, and at others even more gentle, soulful and wistful than Start & Complete. In some ways, About Group are trailblazers. Their ethic of hitting record and seeing what happens – while not an original idea – is certainly unusual in the context the group operate within, and brings into question how blurred the lines are between composition, songwriting and improvisation are.

How did the About Group project first come about, for that first album not under the ‘About Group’ name?

John Coxon: Oh, About? That was on my label. Treader. Alexis was interested in working with myself and Charles Hayward and I suggested that maybe we could call Pat. So we all met up and we just played, all in one evening, and then we kind of edited that together to make the About album. Then, during the gigs that we were playing at that kind of time, Alexis started introducing songs that he’d written, just without telling anyone. He just started singing these songs, and we started making a slightly different kind of music, and then came the second album.

So that was completely unannounced at some gigs you were playing together?

Alexis Taylor: Yeah. The gigs were all improvised, so anything could happen, and part of my improvising was to include songs of mine that maybe had been written but didn’t really have an arrangement or anything in mind. So it wasn’t that I was improvising the songs, I wasn’t scat singing or anything, just sort of embedding them in the context of an improvisation – seeing what would happen if I tried it out. But then the next record, the first one for Domino, was slightly different from that approach because it wasn’t that we went in improvising and then I would drop into songs. It was more that we went in saying, let’s [make] a record of these specific songs that I’d already recorded, piano and vocals demo versions of all those tracks, and played them to John. It wasn’t even clear that it would be an About thing or something else initially, maybe a solo record. But then John said, ‘How about About Group is the actual band for those songs? Maybe something interesting will happen.’

Then we just went in to Abbey Road and recorded the tracks in one day there, without overdubbing or anything. Just sort of went through them without any preparation, and also did some improvising when we were there.

Did that feel risky to you – going into Abbey Road with not much set in stone at all?

AT: It was deliberately risky, in a way. Everyone probably had different approaches to that day. John had recorded for his label by going into Abbey Road…

JC: …and doing like two or three a day.

AT: And then this, for me, was an opportunity to say, ‘Why don’t we record with people who are going to play really interesting things, but they’re not going to know the structures of the songs too well in advance.’ So it was important to me that it was quite a quick thing, and no-one would really get the chance to say ‘Now I’ve worked out my part, I can do it properly.’ That was based not so much on improvised or avant garde music. It was more based on listening to New Morning by Bob Dylan, or Alex Chilton’s Like Flies On Sherbert where it sounds a bit chaotic, where it sounds bit like people are getting the chance to play the first thing they think of, which may not be true, but that’s how it sounds.

Do think that once players listen back and start to develop an idea, that it removes something of that immediacy?

AT: Not always. I’ve made lots of music where you go over it and over it and you think through ideas and you plan things, but for these songs I felt like it could be interesting to not give it that opportunity. But that was just something that I happened to be interested in at that time, and I don’t know that Charles really was thinking about anything to do with that, and I don’t know about Pat either, so…

JC: Everything kind of just happened on the spot.

AT: And if you do it at Abbey Road, then it’s going to be recorded well.

JC: Have you heard the loops from this record?

The loops?

JC: In that session we were just talking about, after we recorded most of the things related to Alexis’ songs, we did a long improvised piece which is about forty minutes long. Subsequent to that we made some looped sections of that, about twenty of them I think. And they come with this record – a bonus sort of thing. I’m really fond of them, I really like them. They’re interesting because they were recorded on the same day as Start & Complete, and they illustrate really the lack of specific purpose on that day of recording.

Musical cohesion is something that both About Group and Hot Chip explore in different ways. Hot Chip coalesce through lengthy planning and composition, while About Group’s music largely occurs spontaneously. How do you feel about the two approaches?

AT: Well, the Hot Chip processing of writing involves lots of improvising at the beginning and no talking – in the same way that About Group doesn’t really involve talking about ‘What shall we do?’ They’re actually closer together than most people would think. It’s more that once you’ve done some recording in Hot Chip that involves lots of free playing, you then sort of start to organise it and edit it, in a more extreme way than we do in About Group. They’re not really opposed to each other.

JC: Well Pat, you do stuff, don’t you, which is involved with composition – ‘heads’ or whatever – and you’ve done your Derek Bailey thing, which was basically transcribing him…

Pat Thomas: … and then I’d improvise on top of it.

JC: So you were transcribing his things?

PT: I used his things as a starting point. I’d use his transcription as the head, then I’d improvise on that. Like Alexis was saying, the approaches are both the same really, and we do edit. We sort of listen through, and know the bits to take out. [Laughs] We’re not going to leave everything in! Although some people are not so precious on that.

AT: Well I think one major difference might be that live is the sort of base thing that you’re using in the finished recording. There’s still room for editing and overdubs, but there’s much less of it than there would be in Hot Chip. The sound that gets created by Charles, Pat, me and Johnny playing in a room, that’s kind of essential to what the records are. Whereas the programming of Joe’s, the songwriting of mine, the playing of mine, the bass guitar playing of Al – those are the things that are essential to Hot Chip records. Particularly the programming of Joe’s, which doesn’t necessarily do things that someone playing by hand would do.

The new album contains a cover of Bacharach and David’s ‘Walk On By’ – and I use ‘cover’ quite loosely. How did that come together?

AT: Well the music that the vocal is on is all improvised, and I guess it’s sort of the third ‘track’ in a 45 minute piece of improvisation that we did. And it had nothing to do with ‘Walk On By’. And then… maybe you suggested…? [points at John Coxon]

JC: … singing over it. I’d been listening to Isaac Hayes’ version of ‘Walk On By’ the day before, and that’s what reminded me. There’s something about the playing on that which reminded me of it, the pace of it and everything, so I started singing over it and suggested it to Alexis.

It does sort of kick in in a similar way, doesn’t it?

JC: Well, yeah. Actually when Charles goes from the closed hi-hat to the [makes crashing open hi-hat sound] is when Alexis chose to start singing the vocal, and then I overdubbed the bass on top of it at exactly that time so that it kind of ‘lifts’, and then the tremolo guitar, I overdubbed that as well, and that was a homage really to the Isaac Hayes version. So those things are controlled after the event, but the bulk of the playing was already done. That’s got the most overdubs of anything on the record.

AT: Also, I’d been quietly interested in the Bacharach-David songs – and particularly the Isaac Hayes versions, because he does one on every album for his first few records – and I’d made a sort of loop of ‘I Just Don’t Know What To Do With Myself’. The Dusty Springfield version. And about a year or two before…

JC: We played it live didn’t we?

AT: … yeah, during a gig with About Group, when I was saying I would drop into songs of mine, I dropped into that long before we had done this on this record. So I guess it was just sort of a preoccupation of mine to try and involve certain of those songs.

JC: It was a great moment, that. We only did it once, didn’t we?

PT: Was that Glastonbury?

JC: Yeah.

AT: In a weird way, that kind of thing of such classic songwriting and 60s soul music meeting with improvisation seems to be quite important to this band, whether or not it’s something we all talk about. Charles is quite keen to not talk about influences and not let things kind of cloud the recording process, whereas John and I really enjoy saying ‘this reminds me of such and such’, and I feel like that’s really integral to what goes on in the music. So you might do lots of things in a very unconscious way, you might also be doing things that are referencing that era of soul music, as well as modern soul music.

Well some of the last songs on the album, particularly ‘I Never Lock That Door’, sound to me very folky and very country – as if there’s a definite influence there. What effect did this have on the songwriting and then also on the improvising?

AT: Often if you’re writing a song, you’re not necessarily writing it with a context in mind. So I basically wrote that while recording it, just improvising a set of words over really repetitive chord changes, no kind of differentiation between the verses and the choruses, so simple that it just cycles round. I think I was just thinking about Charlie Rich – a sort of country pop singer with a record called Behind Closed Doors or something like that, and that got me thinking about that phrase for my song. I thought of it really as a country song, but I didn’t really know what I’d do with it, it’s so trad.

And because it’s so trad, it instantly has so many connotations.

JC: Well it’s interesting because the connotation to me and Alexis was Charlie Rich, but Pat was saying that it reminded him of Dandy Livingstone. Which is quite interesting, because they are related.

PT: Well, and country and western is very popular in West Indian households. When I was growing up I was constantly listening to Jim Reeves and all that sort of thing.

AT: Yeah, lots of country songs get covered in kind of reggae versions. The two worlds are quite happy to coexist… but we didn’t necessarily talk about any of that sort of thing. I would’ve thought that John, knowing the song in advance – it might remind him of great country records – might want to do some slide guitar or something. But instead he’s playing keyboards and samples all the way through, with a sort of arpeggiation that is not necessarily in time with the music. Basically we just approached it in a way that was no approach, because no-one knew what we were going to do with it. And that’s kind of more interesting than thinking, "I’m gonna put a pedal steel guitar on it." Even the fact that it coexists with the other songs on the record doesn’t make sense, and I think About Group records don’t have to make sense. That one might stand out a bit as a kind of mainstream track…

JC: Well, no more than one of the short improvised things.

Pat, you’ve been improvising with electronics and electronic instruments since the late 80s. Before you start putting your hands to keys and improvising, with an instrument like that there’s something a little bit less ‘locked in’ perhaps than a more acoustic instrument, because you can prepare sounds and choose sounds beforehand. So how much preparation was there?

PT: None whatsoever. I didn’t bring any instruments. On the album there’s a beautiful ARP synthesiser, which I’d been dying to play. It’s incredible and it’s all hands on and I can programme things. I mean, modern instruments… there’s no comparison really. I’d always wanted play one, but I’d honestly never played one until I got into the studio that day! So I just sort of, had a look at it, worked out what the filters do, and go for it.

Is that the way you’ve always done it – back with the Tony Oxley Quartet?

PT: Tony Oxley Quartet’s all my own gear. All the stuff’s mine and I’ve got more of an idea what the stuff can do and I could bring samples. This was actually more risky in the sense that I didn’t… we didn’t even know if it would work, did we?

AT: I knew it would work because we’d done Hot Chip records using it at the same studio, but I remember thinking it’d be good if you had the opportunity to use that keyboard, so we just set it up. One of the keyboards I use on this record, I’d never used before either.

PT: The Juno 60?

AT: Yeah. I didn’t know what would happen if I turned various things on, and that’s what ‘Walk On By’ was made out of. Just trying things out as and when recording.

So John, what you’ve done with Spiritualized and Spring Heel Jack treads some of the most similar ground to About Group – putting improvisation into a more conventional, rock-oriented context. What drew you to that over the course of your career?

JC: Well it’s anti-careerism isn’t it? I’ve avoided a ‘career’ in music. Whenever some kids ask me about how to get a career in music I always say we’ve been trying to get out of the music industry ever since we found ourselves in it. I started making pop records, in a sort of conventional way. I mean, the early Spring Heel Jack records are kind of conventional in a way, although they were drawn towards sort of drum & bass and hardcore, that sort of thing… I mean, I guess improvisation just suits me. It suits my abilities and my terrible memory, I find it very difficult to learn and I hate being told what to do. Even a song tells you what to do. I can’t stand it, I don’t like it, learning things. It’s like you’re getting ready for an exam or something. I’d much rather be in the existential world of the improviser, the pure improviser. I really like, enjoy that, and I really like playing with other improvisers who enjoy that sort of thing and don’t need the structure and safety of a song.

So you’ve worked with Evan Parker, Han Bennink and people like them, and presumably they’re all virtuosos and can read music fluently if they want to. Is that something that you’re able to do?

JC: Not really. I can read music at a snail’s pace. I’m not like Alexis.

AT: Hang on, you’re grade eight cello aren’t you?

JC: Well, yeah, but I’m sort of dyslexic with it, I read slow.

AT: … and I can’t even read at this speed he’s talking about.

JC: When I was a kid I was very into learning music and all that, but I found it hard and I could never just read things straight off the page.

AT: That’s exactly how I felt during my learning about music.

JC: But Han and Evan haven’t spent their time reading music. Evan studied botany like I did, and we’re more similar than maybe other musicians actually. There’s something about the sort of science that Evan’s interested in. He certainly doesn’t spend his time reading music.

PT: Yeah, he’ll be the first to admit he can read, but he’s not a big reader. Not into it.

JC: Yeah, he’s all about improvising.

PT: Like with all the great improvisers and world traditions. It’s only in the West that there’s this obsession with reading. I mean, you play because you know it. For instance, if somebody’s giving a lecture, you say they’re a good lecturer if they’re somebody who doesn’t need to have a pile of books there. They know it. It’s the same way in music.

JC: Derek Bailey has this great quote where he says ‘what’s the use in waiting around for somebody to write music for you?’ And he’s right, that’s not what music’s about. It’s an expressionistic thing, and I haven’t read music properly since I was, I don’t know, fifteen.

AT: Yeah it’s interesting, because it’s your improvisation that I was drawn to, yet it was the songs that I was writing that John was drawn to. So I said why don’t we do some of my songs with you improvising on top of them, taking them away from a sort of ‘classic’ sort of thing.

JC: It’s rare to find a good songwriter. Jason [Pierce] is a good songwriter, Alexis is a good songwriter, and there’s a band I worked with a long time ago called Pooka – these two girls, they were folk singers. You just don’t meet good songwriters.

What is it about Alexis’ songwriting that you liked and thought you wanted to work with?

PT: He’s got a good understanding of structure and also of knowing exactly where the hook goes and how to put a hook together. How to put a chorus together, an opening. That’s very rare these days. A lot of people don’t know any of those things, and lack that craftsmanship. I hate to say this in front of him!

JC: To me, the lyrics are very important too. I’ll give you an example, yesterday I was listening to Daft Punk’s ‘Around The World’ with my boy. He asked me why are they saying, "Around the world, around the world, around the world" over and over again, and I said it’s a just a hook. It doesn’t really mean much, but it’s a hook. Rihanna says so and so in such a way because it sounds such a way, and hooks you to it, but doesn’t mean much. Alexis’ songwriting however, can be read on various different levels like all good things. You can see them as hooky, or look into their deeper meaning, the poetic element that they all have. Jason Pierce has the same thing.

David’s lyric for ‘Walk On By’ is a good example. Your arrangement differs so vastly from either the Dionne Warwick or Isaac Hayes versions, yet something of the original still stays.

JC: Yeah, the song survives.

AT: And that’s why I made the point about John being interested in playing to my songs. He’s interested in that notion of ‘serving the song’. If the song is something you’re interested in, you’ll work towards whatever would be the best arrangement for it. Although this band’s ethos at the start was improvising – I wanted to get away from songwriting if anything – we all bond together over Alex Chilton records or Dan Penn records, and songs brought us all together again in this weird way.

JC: And I can’t write songs. I don’t have that sensibility. And although I don’t like being told what to do, I understand and know that it’s good for me.

PT: Haha! I love that!

Apparently this is the last record with Charles Hayward?

AT: Well we made the record together, then he basically just decided he couldn’t commit the time for it.

JC: He couldn’t commit to it ’cause he’s doing this big tour with Massacre.

PT: Yeah, a big tour of Japan with Massacre. He got asked to do a lot of work last year, and we didn’t have anything in the book, so he had to make that decision, and he’s also had some solo stuff coming out too, and the Monkey Puzzle Trio.

AT: Even if he might play with us, he made a pretty definite statement that he wasn’t really able to carry on.

Will About Group record again? Do you have any live gigs?

AT: Yeah, both of those things. We’ve got Susumu Makai, who used to do work under the name Zongamin – they’re kind of really weird dance records – he’s playing bass with us. And Rupert Clerveaux, who was in a band called the Sian Alice Group, is drumming with us. We’ll play gigs with them as the band, and we’ve also planned to make another record and maybe more records. I must admit though, when Charles said that, I was thinking that could mean that we don’t do it any more, but we’ve come to terms with it. I often think of Battles – they had a founding member, Tyondai Braxton, leave and then they just carried on. I really care about Charles’ involvement in this project, but we also really care about doing something together and going beyond that original formation. I don’t know if I’d have said that initially – part of the reason for this whole thing was to play music with him – but I like playing with Pat and John too, so we’ll do something else.

Between The Walls is out Monday July 1st on Domino. About Group play Victoria Dalston on Tuesday July 2nd