In a 1917 review of T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock and Other Observations, Ezra Pound writes that Eliot had ‘not confined himself to genre or to society portraiture.’ The collection exhibited an abstract and novel language that is today exemplary of an extraordinary, albeit staple, modernist vanguard verse. Quorum is William Fuller’s new collection of poetry and it inevitably locates itself in the ‘avant-garde’ poetry department – it’s unlikely that this book will be stocked by your local Waterstone’s. Yet, in the world of contemporary avant-garde poetry, these works are almost pastoral in their subject-matter: Urban life is transformed into otherworldly natural habitats, with cycles of day and night replacing digital clock faces or iPhones. Fuller is not interested in shouting a political message to the world; his writing is measured, restrained and quiet enough to coax the world closer to him: Friends, lend him your ears. In his title poem Fuller proclaims, ‘The world is declared quorate.’ Yet, despite its clarity and conviction, Quorum is an ambivalent song that is sung across forty-five poems, each one consisting of exactly fourteen lines. Fuller’s tone is unsettling – he shapes a world of unknown territories that are also somehow curiously familiar.

Language and subject matter remain abstract, although Fuller does return time and again to certain tropes and themes. It is rare to find poetry that is both conceptual and deeply meaningful; it reads like a linguistic translation of abstract expressionism, comparable to the paintings of Franz Kline in what appears to be an impulsive gesticulation, but is actually a performed expression: this is a carefully composed work of art.

Part of the reason that Fuller’s work feels so hyper expressive is due to his ease with language. He commands description with incredible delicacy and attentiveness:

There’s a faint breeze and a fat fig / and a cut stem.

The soft and fertile ‘breeze…fat’ is sliced apart and made impotent, ‘a cut stem’. He also circumscribes place and event, which lends a heightened sense of importance to his poems despite their size and regulated structure. This is the case with the final sentences in the last poem of Quorum‘s part 1, in which minute hints are coupled with a strange and fearful oddness to produce the weirdest of expressive vignettes:

I see traces of hands / and wings. I see a doll’s eye pedaling toward the sun.

The persistent fourteen-line structure of each poem makes comparison to the sonnet form temptingly easy but somewhat misplaced. The poems avoid any strict metrical rhythm: They remain strikingly intentional in their structure. Yet it soon becomes clear that the line structure is set according to the margins of a Word document – a margin that changes from poem to poem. This begs the question of how much intentionality Fuller invested into the form of his poems prior to their margin adjustments. They sit boxy on the pages; even the fourteenth line snakes its way to the bottom-right corner to complete the cuboid shape. In this respect the poems follow in the aesthetic shoes of shape poetry, particularly the concrete poems of Carl Andre in which materiality is often emphasised over syntax. The fact that Fuller has not chosen to have his poems laid out in a ‘justified’ format makes this adjustment all the more apparent. Their jagged right edge sharply contrasts with the cleanly aligned strip to the left.

Despite the prescience of margin adjustments, Microsoft Word is perhaps not so much Fuller’s artistic director as it is his helpful editor. Line breaks in Quorum feel far from arbitrary; a point in question is the thud of ‘Thoughts shoot’ in ‘The Lecture of Sheep’:

Thoughts shoot / out like flames, soft, white, and thin.

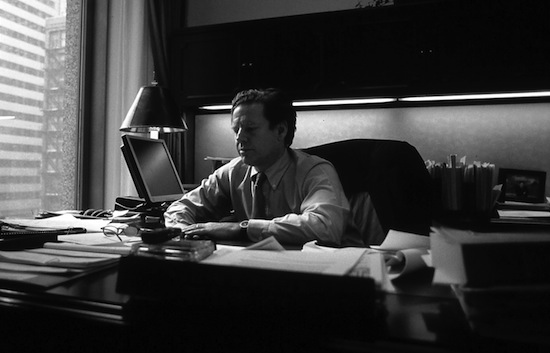

Here the line break emphasises the excessive aggression of hurtling thoughts that sit curiously at odds with their delicate and seemingly sickly flame form on the following line. This strange push and pull sentiment haunts the collection – perhaps a preoccupation of Fuller’s. His own position as the chief fiduciary officer of Chicago’s Northern Trust Company at first glance appears to be at odds with his role as a poet – a job title that famously favours the poorer beatniks and romantic consumptives. Yet although his well-paid employment inevitably seeps into his poetry – a little quip of ‘Don’t sell’ in ‘Quorum’ – it would be reductive to see the collection as an echo of Fuller’s day job. In fact much of the collection is concerned with re-describing daily life in such a way that it takes on an extraordinary and phantasmagorical quality:

Back / inside everyone walked around oblivious as usual but I noticed their / folders were full of tiny eyes looking out

The allegorical aspects of the lines are heightened by the reference to officialdom with its “folders”, and also the kind of office mentality that accommodates this oblivious walking around. Yet these tropes grow strange; the eyes in the folder look outward and observe the mindless people: office work policing its workers.

There is a sort of abstract time warp in many of these poems, as Fuller transforms time into something spatial and at times ironic. His opening piece ‘Plastic Nature’ tells us that

the present pictures itself / asleep beside a sea of creosote fences

We discover that the present itself is in fact not present at all. It is instead imagining itself somewhere else, in an alternative temporal landscape. Neither is the present always absent – many of the poems are written with great attention to the actively engaged ‘here and now.’ This gives the work a sense of urgency; the present becomes intensely important because at any moment anything could happen. The spectre of time becomes fatalistic in ‘Do So Personally’:

a vast / collection of birds and insects at risk of becoming irrelevant now / that their energy has been replaced by what the dam generates

One imagines a menagerie of tired creatures wiling away their time, unable even to achieve extinction. Technology advances but it does not keep the same time as nature. The fallout is bizarre and the world in Quorum is presented as at odds with itself. This occurs again with the following poem ‘Yondyr’, which begins:

The dawn huddles near the far end of a great pier stretching / into space

Time becomes elastic as it conjoins with space, and “dawn” is reduced to a frightened little pile in a corner, dwarfed by the vast and grandiose pier. These shifts in perspective have a surrealist quality, as though all that we thought we knew has been altered, or has actually dissolved altogether. It is this disjunctive temporal lapse that brings us face to face with Marx’s famous warning that ‘All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.’ If Fuller is indeed following this trajectory then his aim, alongside Marx, would be to unveil the true conditions of life: it is only after the solid has become liquid that humans can come to realise their real living conditions. This would be in keeping with Quorum’s indirect address – an address that exercises the utmost restraint and only considers a world through dreamlike allusion. Despite Quorum‘s uncanny temporal dissolve, there are times when Fuller achieves a strange familiarity – a space in his otherworldly terrain in which the reader might recognise themselves. Perhaps Fuller is encouraging us to glimpse at this liquifying world; to begin to feel the extent of our dreamlike existence. Yet when it comes to deciding whether his strange habitat exists as either a reified present or a futuristic dystopia, Fuller refuses to rest in either camp. Indeed, time could tilt either way with titles such as ‘The Lecture of Sheep’ and ‘Phases of the Sun.’

There are continual references to a communised “we”, as though Fuller is imagining himself with a coterie of companions. This collective voice is placed alongside the more familiar lyric “I” – in contrast as a more lonely and desolate figure. “We” hums like a cacophonous chorus, presenting lines as quorate and also weighty with multiplicity. Again the fluctuation between “we” and “I” emphasises the fantastical quality of Quorum. Despite being grammatically correct, Fuller’s sentences shudder through his use of unconventional syntax. Words quake under the pressure of this grammar, for instance with his Blakean:

Beneath them, new-born lambs / adjust to earth.

This “to earth” exists as simultaneously noun and verb, giving the sentence a double meaning: firstly of lambs becoming familiar with their earthly environment and secondly, in a stranger sense, of otherworldly lambs acting out this new verb, ‘to earth’. The command that Fuller has over his language is striking and also emphasises the fact that he is refusing to adhere to rules that he is obviously familiar with. Or is he adjusting the rules? Throughout Quorum it feels as though Fuller is discovering that language itself has achieved a radical new level of pliability. This is avant-garde poetry at its most elastically exciting and linguistically thrilling.

Quorum is available now, published by Seagull Books