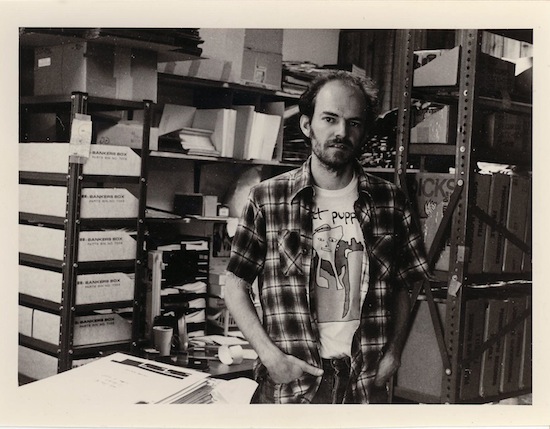

There has been a torrent of books written in the last decade devoted to the history of alternative and underground music, offering up stories that have previously gone undocumented. But one author, and one book in particular is often left out of this burgeoning list – the extraordinary Rock And The Pop Narcotic by Joe Carducci. Working as both A&R man and record producer at the now legendary SST Records in Los Angeles from 1981 to 1985, Carducci was at the heart of a revolutionary label with a core of LA-based bands that sought to change the face of independent music at a time when that term was barely defined.

He did more than most in determining what form that independent music would be, and later, when almost no-one cared to weigh the merits of bands like Black Flag, Minutemen or Saint Vitus, Carducci set that record straight with a book that documented the SST phenomenon while also extrapolating an entire aesthetic of rock from its many achievements. Carducci’s avowed tenet that rock is enacted fully within a “small band format” is bracing and controversial to this day, but for this writer it is the most persuasive argument that has ever been set down in paper in terms of rock’s greatest attributes. His advocacy of a kinetic energy in opposition to the then prevailing 80s synth pop and recurrent Tin Pan Alley/ hit factory machine is as provocative a stance in 2013 as it was in 1991.

Carducci’s later work is less abrasive but just as impactful. The early death of SST photographer Naomi Petersen drove Carducci to write Enter Naomi. Part biography, part topographical history of LA, it is a heartbreaking account of a life lived to the fullest but seemingly at a remove from everyone. Petersen’s visual contributions to rock culture are also celebrated with loving reproductions of key images, but what strikes hardest is the sense of loss Carducci feels at the death of a great friend.

With his 2012 anthology Life against Dementia, Carducci has proved himself a master of the short form essay, compiling work from his blog The New Vulgate as well as magazine articles and sleeve notes dating back to the late 1970s. Among the most powerful is his memorial piece for the late Saint Vitus drummer Armando Acosta and a brilliant précis on the career of the undervalued actor Charles Bronson. A book of his terse and evocative screenplays published under the title Wyoming Stories completes a remarkable series of work.

It’s been more than twenty years since you first published Rock And The Pop Narcotic: do you feel that any of the more recent books that chronicle aspects of the SST/underground era of the 80s have contributed as positively as your book did? I’m thinking of Azerrad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life and Reynolds’s chapter on SST in Rip It Up & Start Again, primarily.

Joe Carducci: None of the rock writers had the perspective on the whole of it that I did. I put the American shops together at Systematic. It took three years, whereas in the UK Rough Trade was written up in the NME and every shop called them up immediately! At Systematic we also had a good mail order service and a label [Optional Music], so we knew the retailers, labels, bands, radio people… all their ambitions and retardations, etc. That’s why Greg [Ginn] and Chuck [Dukowski] were interested in having me run SST for them. So that put me together with the bands who were learning about the clubs and promoters. I would also say that [Glen Lockett, SST house producer] Spot’s M.O. of recording bands straight took over from the failed sell out style of the new wave sound amelioration. So none of the main rock critics know any of this. And they resist it when they come across it because it threatens everything they’ve built up from first listen to a band’s record. And a record is usually a lie, especially the ones they like. Where the books by Azerrad, Reynolds and others are worth reading it’s when they do their reporting and get what good bands have to say down.

I found an old interview from The WIRE magazine (conducted by Simon Reynolds in 1996) that sought to portray you as some sort of Robert Bly-esque figure and the theories you expounded in Rock And The Pop Narcotic as nothing more than macho stereotypes – even demeaning Henry Rollins as a "sweat hog". Coming from the UK, where to enjoy rock/ metal genres can still lead to writers like myself being maligned as "rockist" and illegitimate, this has led to an almost total lack of rock-based criticism, outside of small, niche publications and online sources. In the wake of your book, do you see any other areas where the rock debate has moved forward at all?

JC: I guess not, but at this point the writing hardly matters except to look back and underline the best of the past for kids. The music has failed, after its development was interrupted in America by the radio and Rolling Stone blockade (in the UK maybe the break was with Bowie and McLaren). Unless young bands go back to steal fire from pre-1980s music they aren’t going to contribute much. The best of the early sixties folk scene was based on exhuming the late 20s and 30s so this has happened [before] but the dissolving of mass media by the web destroys any coherence of the underground as well as the mainstream. So I assume the same re-tracking from the past is likely happening but not adding up to anything like the Holy Modal Rounders, Koerner, Ray & Glover, or Michael Hurley.

As far as Reynolds’s piece in The Wire, I think he was translating an American phenomena for the UK music elite. I think my book and SST generally managed to interest UK writers since they were faced with it suddenly and it struck them as so non-Brit and out of sequence with British developments. Clinton Heylin put excerpts from Rock And The Pop Narcotic almost immediately into his Penguin Book Of Rock & Roll Writing. This has never happened to any of my writing in any American anthology. Simon Reynolds’ review of the revised edition of Rock And The Pop Narcotic for Art Forum doesn’t have that “translation” concern of The WIRE piece. Barney Hoskyns had introduced L.A. punk to the NME in 1982 (I think) and at least tacked on Black Flag at the end of his portrait of LA music, ‘Waiting For The Sun’. James Parker reviewed my book along with an interview aspect in The Idler and wrote up Enter Naomi most perceptively. Of the American critics, they had to deal with the worst editors imaginable, either patterning themselves after (Rolling Stone founder Jann) Wenner, or (New York Magazine founder Clay) Felker, neither of whom cared about music. I don’t know how much better [Robert] Christgau’s influence has been but at least it’s music oriented. Michael Azerrad mentioned in an interview that Rock & The Pop Narcotic had changed how writers viewed heavy metal, but it’s just too late to matter given the state of music. The best music is made by the last important generation – players now in their 50s and 60s, not kids.

I was also intrigued by your description of the Black Flag/ SST having more to do with the radical lineage of the Black Panthers, Weathermen, SLA rather than a purely musical one. It certainly makes sense to me given that your descriptions of life in LA at that time and at the label as something akin to a combat zone with an added siege mentality thrown into the mix for good measure. How did you manage to not just survive but also thrive in such an extreme environment?

JC: It was more that we didn’t have this pseudo ironic detachment of the indie world hipsters you see triumphant today. I tried to get at that in my description of the immigrant and working class threads in our mostly suburban lives to that point. SST bands played and practised hard and were hard on each other and didn’t quit so easily. We weren’t post modern maybe in the way that the UK scene became very quickly after 82.

What led your decision to leave Los Angeles and pursue writing once again? And what sort of writing work were you engaged in then?

JC: I had wanted to give LA another try so SST was that opportunity. Once I had my own place in 84 I got back to writing screenplays. I had hoped to try to get an agent and figure that out before moving back to Chicago but that wasn’t so easy and didn’t happen. I also began reading for Rock And The Pop Narcotic before leaving LA. It took another four years in Chicago to finish it, after which I wrote my first good script, The Winter Hand, which I hope to make here in Wyoming in a couple of years.

When you first wrote your online tribute to Naomi Petersen in 2005, how long afterwards did you think about extending it into a book?

JC: At first I thought about just finding out the minimal information about what happened to her. I did a people search to find an address for who I guessed were family and got in touch with Naomi’s brother just before posting that, I believe. Then, after visiting him and seeing her material at his house and meeting her mother, I was convinced. But really it was her brother Chris who let me do it.

Did everyone you approach for interviews/ recollections for the book reply?

JC: No, a lot of people involved had the first impulse to respect privacy, their own if not Naomi’s. They couldn’t imagine the kind of book it would be, so they didn’t say much. I imagine after they read the book they’d wished they’d told me more. But that was mostly about the past. I don’t think anybody I know knew much about Naomi’s last decade. I managed, I think, to get my email address and a query to James Hetfield who Naomi spent time with before he pulled up and got sober, but I didn’t really expect to hear from him. Didn’t hear from Duff McKagan either, and I was hoping her name might pop up in his memoir or Slash’s but no.

What were the reactions of other members of the SST inner circle to the book itself once it was published?

JC: I didn’t hear a lot really. I believe they all liked the book. I had good SST turnout at my book-readings in LA, and Thurston Moore, Byron Coley, and half the rock critics in New York were at those readings. People generally don’t know my story-telling skills since my screenplays haven’t been produced. So I gather the book and the earlier online essay kind of sneak up on the reader; even on those who’ve read Rock And The Pop Narcotic. I think my best review was by Scott Weinrich [of Saint Vitus and Shrinebuilder] who came across the online piece via Scott Reeder and like a lot of people hadn’t known she’d died. It must’ve been brutal for him to read, but he emailed: “It’s beautiful and brilliant.” I think Wino was Naomi’s idea of the perfect rock musician.

In the book you mention that the first bands Naomi photographed were Saccharine Trust and Saint Vitus. Was her ability as a camera immediately evident from those early shots?

JC: I didn’t know anything about photography and of course we didn’t want our bands artied up in the usual way of the new wave, or the earlier style. So she was immediately able to deliver usable images which required the kind of sympatico that meant she understood the unvarnished anti-art aspects of punk ambition. The shot of Saccharine Trust in Enter Naomi and the Saint Vitus shot in Life Against Dementia are from those first sessions. In Rock And The Pop Narcotic the Husker Du shot is from the first gig she covered for us – that one has its technical roughness but I love the composition and you can tell the band was wired and barely standing still for her. She had shot Black Flag for herself a bit before then. But as the line-ups changed and the band was on ice due to the Unicorn lawsuit we didn’t have her shoot them for our use until later.

What in your opinion distinguishes Naomi’s photography from others working on the LA independent scene at the time?

JC: One thing common to a lot of her posed band shots is that there’s often one member of the band looking away at something. So there’s a loose off-hand sense of being captured quickly. An awful lot of her 1981-1983 stuff and some later East Coast work was lost. I hope there’s amazing stuff in the unmarked negatives we have, but there’s that tragedy too.

Can you tell me about the non-music business-related books that you’ve written since the publication of Rock & The Pop Narcotic?

JC: The new book, Life Against Dementia, is an anthology and about half of it is music, one quarter film including material from work on my next book, Stone Male – Requiem For The Living Picture, which is about the action-film and its acting style going back to the silent era, and one quarter on political stuff. The earliest stuff is a piece on film I wrote for an anarchist paper called The Match! in 1975 when I was 19, and some music and film pieces I wrote when I was at Systematic before I went to SST. I should’ve done some writing while at SST when D. Boon and Raymond Pettibon asked me, but I was writing the PR stuff and by 1984 had resumed writing screenplays once I wasn’t living at the office any more. Wyoming Stories is a collection of the three Wyoming-set screenplays I wrote after Rock & The Pop Narcotic, each of which will get made in the next five years. There’s another ten scripts but not sure I’ll publish those. I started Stone Male in 1991 right after finishing Rock And The Pop Narcotic and all the other stuff has been produced during interruptions in this work, so I see it as being a big book like the Rock… book, but much better researched and better written.

Can you tell me more about your blog The New Vulgate?

JC: We tried a few publication ideas in print and online and finally the blog seemed the way to go. I read a lot of newspapers and magazines so I excerpt and link to the best of that stuff, then I (or some friend) often have an essay to go with that plus graphic material, drawings, paintings, photographs. We were weekly for a year and now seem to have settled into every three of four weeks. Many of the newer pieces in Life Against Dementia originate in the Vulgate; the title essay is reworked from a shorter essay that appeared in Arthur magazine No. 1.

What are your thoughts on the announcement of a Black Flag reunion (with Ron Reyes on vocals) and the existence of another touring line up (featuring Keith Morris and Bill Stevenson) of the band?

JC: Bill had asked me for band name suggestions recently, but I didn’t realize how directly they wanted to reference Black Flag! What the ‘Flag IIII’ name signals to me is that Keith, Chuck, Stephen, and Bill are owed money and don’t care what Greg thinks. Greg has an interest in demonstrating that Black Flag does not equal Henry Rollins so I figured he might someday get a line-up back together with one of the other singers. I thought Greg may have gone with a drum machine in the nineties so as to directly contradict my book! He can be like that, though he also was losing patience with working with other musicians. Each additional member of a band complicates things and adds one more veto to decision-making. That said it is also true that if Greg is not doing Black Flag it opens up a door for the other ex-members to go out as the band. It’s kind of shocking to see what cover bands get away with these days advertising their tribute bands. Greg learned a lot fighting Unicorn in the courts in 82-83 and it changed him; he does understand protecting ownership of Black Flag. John Kay did the same when Goldy McJohn and others tried to relaunch a Steppenwolf.

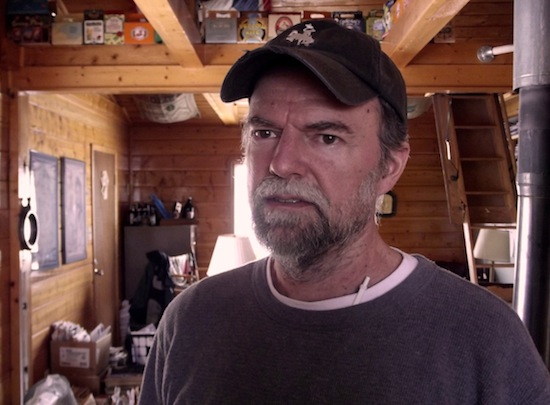

Your book Wyoming Stories is a compilation of your screenplays set in that state. What did this specific style of writing offer to you creatively, and has the screenplay been rendered obsolete?

JC: I was only ever interested in writing screenplays. I’d while away the time in boring classes in high school the in early seventies by writing sight-gags like it was still the 1920s. I’d read novels but didn’t think you needed to fill in all that detail any more for the reader. I love the time-stretching that [someone like] Dostoevsky would do, but in the 19th Century a reader had time for that with no mass media or even the phone to interrupt. I remember sections of the novel, M/F, by Anthony Burgess is dialogue-only without even character names denoted. You can follow it fine so what’s the point of all the scenic filler. But I do write screenplays for the reader, unlike the kind of flat tuneless scripts you see passed around in Hollywood; those really have no reader interest to them at all but are just properties that represent a genre or setting that some director or actor might be interested in and they’ll have to put it through rewrites with their favourite writers until maybe just before shooting it might have some sort of charm for a reader. I probably should have written novels just because of the nature of Hollywood’s closed shop. They’d rather buy rights to a novel than read a spec script. I thought I might be able to move sideways from music to film while in Los Angeles in the mid-eighties, but until Nirvana went platinum with their second album there was zero interest in the phenomenon of LA punk rock on the part of Hollywood. The eighties movie was Steven Spielberg and John Hughes… just polishing up suburban-styled mass escapism.

You’ve said to me that "there is a kind of mainstream media memory [in the States] where the papers and mags know that they have actively ignored that era’s most vital culture. Editorially they have a hard time approaching that period". What do you think these media outlets in the US (and to a certain extent here) hope to gain by attempting to pay attention to those ignored aspects of culture now?

JC: I expect we may see this with regard to the duelling Black Flag reunion action. They’ll consult Wikipedia and use it like a bluffer’s guide, because now they know it’s their culture, though what copy they produce will likely reveal that it is not. Everyone is a college grad now, but they study just the soft sciences and media arts which don’t even model useable metaphors as science or the classical arts do in spades. The contemporary liberal arts graduate gets little but pretentions out of his education and so there’s usually an undercurrent of hostility to even have to acknowledge any of this art from before his time. It was better when an Ed Sullivan was simply a TV presenter who didn’t feel the need to convince himself or you that he understood Elvis or The Doors as anything more than another variety act. Jan Wenner and Lorne Michaels should have learned from Ed and we’d have been better off. Michaels never had The Ramones on Saturday Night which was the hippest offering of New York, but NYC has never really been a rock & roll city and by the mid-seventies the mass media was going to try to get by on hip comedy – it lost the beat and was relieved to be able to.

Radio and media allowed this ignorance to pass, whereas just a year or two earlier Andy Warhol was going to Robin Trower gigs.

But I think of this every time I hear The Ramones now played over the PA at a major league sporting event, which only began once they were all safely dead. I expect the writers who might make some sense of Black Flag today aren’t quite in place at major publications, except for maybe Ben Ratliff at NY Times. He’s written well about Saint Vitus recently.

What are you currently working on in terms of writing?

JC: I’m wrapping up a period of reading and film watching before picking back up my first draft of the film book, Stone Male – Requiem For The Living Picture. I wrote the first full draft four years ago from material written earlier but I had to get a better handle on the silent era and also fifties/ sixties television which was a real mill for actors, writers and directors, much of it low budget and slapdash enough to reveal a lot about performers and the form. Stone Male is primarily a book about film acting in the action film style which developed out of non-professional actors who could ride horses or take falls. They weren’t all good at acting for the camera but the ones that were created a great new measure of authenticity for the screen which was followed by better trained actors who came later. In the sound era I’d say that Ben Johnson, Richard Farnsworth, and Jim Brown were the gold standard – a wrangler, a stuntman, and an athlete – each incapable of hitting a wrong note or overdoing anything. The book also covers what Hollywood did to classical forms of drama and how that worked for the audience it made.

Joe Carducci’s books are all available from Redoubt Press at Night Heron Books, Laramie, Wyoming