In tradition dating back to Homer, epic poetry often begins not at the start of the story but in the middle of the action – in media res. The historian Horace was likely the first to use this term, circa 13 BCE, saying that the ideal poet ‘hurries to the action and snatches the listener into the middle of things,’ a technique Homer used in both the Iliad and the Odyssey. This technique continued to be popular in later epics, including the Aeneid and Paradise Lost.

Anne Carson, then, was likely hoping cast her new work, Red Doc> (yes, including the greater-than symbol) as something of a modern epic. Carson, who is a Classics scholar and translator, begins her story this way:

Goodlooking boy wasn’t he / yes/ blond/

yes/ I do vaguely

/ you never liked

him / bit of a

rebel / so you

said / he’s the

one wore lizard

pants and

While we can debate whether she ‘hurries to the action,’ by beginning with a spoken memory, Carson certainly doesn’t waste time giving information about the conversation that opens her story. She does not reveal the identity of the speaker, nor does she include a list of characters, which might help the reader make sense for themselves of those characters and the plot in which they figure.

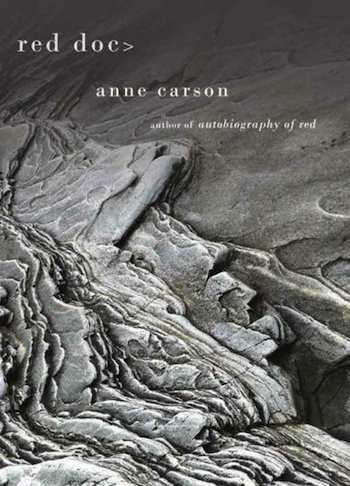

Some of the plot is known in advance, by way of Carson’s much celebrated Autobiography of Red, which chronicles the coming-of-age of a red, winged creature named Geryon, and forms a prequel to Red Doc>. In Autobiography of Red, Geryon has a love affair with a man named Herakles. Red Doc>, carries on their story ‘in a very different style and with changed names,’ as Carson writes in the book’s dust jacket.

The very different style is what is first noticeable to the reader. Autobiography of Red begins before the action: ‘He came after Homer and before Gertrude Stein, a difficult interval for a poet. Born about 650 B.C. on the north coast of Sicily in a city called Himera, he lived among refugees who spoke a mixed dialect of Chalcidian and Doric. A refugee population is hungry for language and aware that anything can happen,’ Carson writes, framing her story. That text

alternates between poetry and prose sections, often containing verse with very long lines.

Meanwhile, Red Doc’s> form alternates between centre-justified verse and fully justified, small paragraphs that leave plenty of white space. These structural elements point to another striking feature of her work – the confusing, or at least far from standard, positioning of Carson’s line breaks. In the same way that Carson writes in media res, her line breaks serve to lend an epic form to her work, mirroring the Classics, written without punctuation. It is this apparent desire to make Red Doc> into an epic in its own right that likely inspired the author to change the characters’ names, in something of an attempt to transform them into more “timeless” figures. Geryon is now simply named G; Herakles is known as Sad.

But are these decisions about characters’ names, these variations in form, really anything more than self-indulgent stabs at literary immortality? Carson goes to great pains to push the limits of form but fails to give her characters much in the way of individual personalities. Unlike other poets who experiment with form, Carson’s experiments fail to pay off or actualise the desire to write a contemporary epic.

However, Carson’s language is stunning when she leaves behind the pretention and focuses on the story, which is admittedly often hard to follow. As G and Sad reunite, some of the pages feature breathtaking and unexpected language and even an emotional quality that is nothing if not surprising. The scene that describes the couple’s previous parting and refers to a ‘farewell letter erased and / rewritten so many times it tore through the paper./ Tearstained laughter a / phrase G blushes to remember. Talking is like / drowning etc. He had the letter on the kitchen /counter. Moved it.’ After the first sex (surprisingly, between Sad and Ida, not Sad and G), ‘[t]he long body is / always a surprise. The / actual touching neither a positive nor negative / experience they each/ would admit but no one / does. A new tract of / nature is open.’

By the time the characters have driven into a glacier in a cave and are fending off ice bats described as being the size of barns, reading the book for its plot is a lost cause, and a reader’s best bet is to read for the beauty of the language when it comes and hold onto what scant narrative threads there are. There are also some nice moments of self-reference, such as when Sad asks G how his autobiography is going (a likely reference to Autobiography of Red). Toward the beginning, in the first of many Proust references, Ida remarks ‘well I’m / not fond of

those multivolume things,’ which could be a jab at both Proust and Carson’s own sprawling experiment. Proust is mentioned often in the book, but name-dropping him doesn’t add much to the story. Late on, we learn of G’s obsession with Proust, which goes some way – though somewhat belatedly – toward making sense of these literary clangers, and the Proust references are most successful when they tie directly in with G’s own fixation. In one scene, G thinks about a scene from volume V where Marcel watches his sleeping lover and meditates on whether or not his lover, Albertine, could have stayed asleep throughout: ‘Albertine / continuait de dormir. He says he likes her better / asleep because she loses / her humanity and is just a / plant.’

The occasionally beautiful language gets interrupted periodically by a reoccurring section, always entitled ‘Wife of Brain,’ always what could be best described as a “centre-justified verse-like-thing.” Regardless of its proper noun, the content in any instance of ‘Wife of Brain’ does not contribute much to the narrative on any wider scale. In fact, a better editor might have cut the ‘Wife of Brain’ refrain completely.

In many ways, Carson shares traits with the American poet Anne Waldman, who recently published IOVIS, a trilogy of over a thousand pages that claims to discuss the wrongdoings of the patriarchy. While Carson has her own formal experiments, Waldman alternates between verse (often complete with things like drawings of mushrooms), letters, and lists. Carson and Waldman both not only play fast and loose with form but heavily mix references from classical and modern times alike. Both writers use a collage of form and content, which tries for timelessness but ultimately is an overly ambitious agenda. Their choices, especially when it comes to form, often seem arbitrary: both writers are on when they’re on, but those moments get overshadowed by pretension of form and over-reaching of the whole project.

Carson ends on an open note; one that suggests G and Sad could appear again, maybe again under different names and different forms. Despite what often feels like the characters’ lack of depth, it would be nice to check in on them again in a few years. Hopefully, by then, Carson will focus on what she does best and leave the pretentious form and confused narrative structure behind.

Red Doc> is published 4th of July by Jonathan Cape in the UK, and was published 5th of March in the US by Knopf