No wonder, as a period of musical innovation morphs into an era of refinement and recontextualisation, that a refined sense of context nudges ever closer to pole position on the starting grid of critical tools favoured by some writers. Take the reaction to Swedish electronic duo The Knife’s new album – the militantly self-explanatory Shaking The Habitual – for example. And most notably take the effervescent and fountainous reaction to Shaking The Habitual by Tiny Mix Tapes writer Birkut who says the album is a "an aural clusterfuck of liberated curiosity and compromise". (To be fair, I agree with a lot of what Birkut says, I just found myself unable to comfortably accommodate the girth of his verboseness, and found myself unable to sit down for several hours after reading it.)

It’s not that I dislike the album (I don’t, I think it’s ace) I’m simply mildly sceptical of the supposed hidden meaning or radicalism of its eclecticism – or even the idea that it’s eclectic full stop. And even then it’s really only the reaction to the album’s slightly daft and long ambient drone section, ‘Old Dreams Waiting To Be Realised’, that does my head in because this track disrupts what is an otherwise effortlessly inventive and exhilarating pop record with something that’s essentially relatively weak in the terms of its own individual field.

Perhaps predictably Birkut gets his lemon-scented knickerbockers into a twist over the track:

"[The track’s] length is part of the sibling’s re-evaluation as to what an album, or the perceived construct of an album, should constitute. It doesn’t play into a specific issue, but takes its title from egalitarian ideals and principals from the past that have not come into effect: "classless society, real democracy, all peoples’ right to move and be in the world with the same circumstances…" Sonically, that premise is completely undetectable, and the results call for an appalling amount of patience. As a long-form drone arrangement, it manages variation and even structure in its garbled tide, neither acting as a breakwater between songs — it’s far too extensive for that — nor a moment of calm after the grinding intensity of ‘Crake’. However, as a standalone piece, it fails to achieve the same level of fascination as, say, Kevin Drumm’s 150-minute Tannenbaum or the tonal elegance of Mohammad’s Som Sakrifis. Instead, it it provides an additional layer of complexity that ultimately questions one’s motives for engagement. It might be out of place in the context of the surrounding material, but when taking this hellion on in a single hit, it’s enchanting: it’s the shiny green jumpsuit to an argument about ‘real democracy,’ intriguing by its very nature and a complement to the project’s sheer absurdity."

Feel the length! Accommodate the girth! But what of its intrinsic worth though? Even Birkut is (I think) forced to admit that it’s not really that good when you compare it to other drone pieces – especially when they’re two and a half hours long and about a Christmas tree. Essentially, this track has become a talking point simply because of the neighbourhood it lives in, despite being the worst track on a great album and a poor indicator of what a particular genre is offering up at the moment.

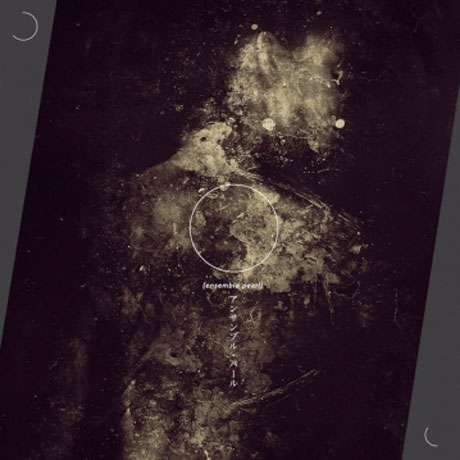

It is instructive, then, to compare this track to ‘Giant’ – the central drone track on (Ensemble Pearl)’s recently released self-titled debut album. Obviously talking about the "right" or "wrong" way to produce drone is facile, but the rich inventiveness of this track points to what can be achieved with an intimate knowledge of one’s genre accrued over a lifetime of work and practice – as rockist a statement as that undoubtedly is. It is a ten minute long, multi-layered, analogue tone which, on the surface of it, only really alters in pitch at a tempo that ebbs and flows slightly. While it’s not surprising to read that The Knife’s track was made with electronics, it really is jaw dropping to learn that (Ensemble Pearl)’s was just made with a guitar. The track was written by Stephen O’Malley of Sunn O))) and KTL as part of a score he originally penned for an ensemble to perform at the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter arts venue near Oslo, Norway, four years ago. While the score itself is open to various instrumentation, in this instance O’Malley asked Japanese psych rock savant Michio Kurihara to play it on guitar with the simple instruction: make it sound like giant Pacific waves. (Something also represented by Simon Fowler’s pointillist take on Japanese art on the inner gatefold, depicting a powerful tsunami creating a tunnel stretching up into a cloudy sky.)

Michio Kurihara is one of Japan’s most notable guitarists, with a very distinctive, elemental and fetishised psych sound developed since the 1980s with the Tokyo outfit Ghost, and more recently on many collaborations with Boris (those interested should check out the blistering acid rock collaborative album Rainbow). Here on ‘Giant’ he uses Fender Twin Reverb amps, Zvex pedals, racks of Roland Space Echo tape delay machines, line boosters, treble boosters and slides to create a sound, so warm, so vibrant, so viscous, it threatens to melt through your speakers and straight through your floor as if you were listening to God’s own Buchla modular synth. O’Malley describes him as "a magician" and I find it hard to disagree. This is a guitarist with the kind of singular talent currently possessed by none of his peers; the kind that Robert Fripp had when he was at the height of his powers.

And (here comes the slightly grumpy old man bit) no-one will pay that much attention to (Ensemble Pearl) because, well, it’s just drone guys doing another drone album, and it’s not a real talking point LP made by an arty synth pop duo who aren’t shy of talking critical theory and entitlement politics. It’s just a shame, that’s all, because it doesn’t matter what kind of music you put ‘Giant’ next to, it remains quite literally sublime – i.e. it creates a stirring sense of awe and fear in the listener, by creating an abstract representation of a facet of nature that we are right to be humbled by and terrified of: giant oceanic waves.

(Ensemble Pearl) is O’Malley and Kurihara on guitars, Atsuo from Boris on drums and Bill Herzog from Jesse Sykes’ band The Sweet Hereafter on bass. All of them bar Kurihara played together on the successful Sunn O))) and Boris collaborative album Altar in 2006, but this isn’t a sequel and, more to the point, doesn’t really sound anything like it. Instead the link is a social one: experimental drone rock played this well depends on an intimacy and shared vision between people who can ‘read’ each other with a frightening degree of insight.

The album was born in 2009 when O’Malley was commissioned to write a score for D.A.C.M. and Gisele Vienne’s theatre piece This Is How You Will Disappear. The sessions were very productive, and enough material was produced to kick start the (Ensemble Pearl) project. The group returned to the recordings last year to finish them off and fashion them into this album.

The track ‘Wray’ was influenced by Randall Dunn (who mixed the album in Seattle and also appeared on Altar) and his love for surf rock. Named for Link Wray, the track refers – in production terms at least – to the earliest surf recordings of the 1950s and 1960s which used spring reverb, tape delay and compression to get very raw, ‘twanging’ and primitive metallic guitar tones. The track itself doesn’t sound anything like ‘Rumble’, instead being an introspective piece with delicately scratched string instruments, arranged by Eyvind Kang (also an alumnus of Altar) and Timba Harris on cello; their work pays tribute to the work of Satyajit Ray – the Indian film auteur and soundtrack composer. Again the sculpture of the guitar noise is jaw-dropping, sounding more like Boards Of Canada or Tangerine Dream circa Zeit than Sunn O))) or Boris.

There is a tip of the cap to another giant of film music, Ennio Morricone, on the suitably epic ‘Island Epiphany’. This is one of three lengthy tracks (also including ‘Sexy Angle’ and ‘Ghost Parade’) which also have an audible debt to late period Earth and their lugubrious folk and Americana-influenced post-doom. However, all due respect to Dylan Carlson, there’s simply a lot more going on here behind O’Malley and Herzog’s tolling chord progressions and Atsuo’s primal drum patterns. Both bands have a widescreen panoramic vision, but the depth of detail here is enough to drown in. Their sympatico and crypto-psychic vision, which is enhanced with rich, deep listening details of dub and echo that punch the vivid scene they conjure up violently out into vivid 3D, unfolds at a regal pace. But really this is the solid framework needed for Kurihara to have one last lysergic assault on your senses, teasing what sounds like anguished screaming, the rattle of thunder and the scraping of cloven hooves on dusty mountain paths out of his guitar.

And it would be a shame if people missed all of this, simply because it was erroneously perceived as "more of the same".