In a 1960s music scene of wannabe Byrons and Shelleys, nobody was more committed to the dream of the doomed artist than Nicholas Ridley Drake. The Cambridge University student flirted with the idea, rhymed his martyrdom (“Safe in your place deep in the earth/That’s when they’ll know what you were truly worth,”) and had accepted its invitation by the age of 26. A few thousand records were sold.

It doesn’t seem enough, really, to account for the journey to legend. And much of the songwriter’s fame, in the US at least, hinges on a VW commercial which introduced ‘Pink Moon’ to the Napster generation, and triggered a heated debate about the ethics of pop in advertising. But the clue to the fuss was in the music; on the cusp of the millennium, the song of a young man who had been dead for 25 years sounded utterly contemporary.

Drake’s background was exotic in a colonial upper classes kind of way; born in Rangoon, he grew up between boarding schools and a mother whose eccentric piano compositions would be a formative influence on his own music. While he wrestled with the agonies of public performance at the turn of the ’70s, his actress sister Gabrielle was turning into a sex symbol for pubescent British boys on a TV show called UFO.

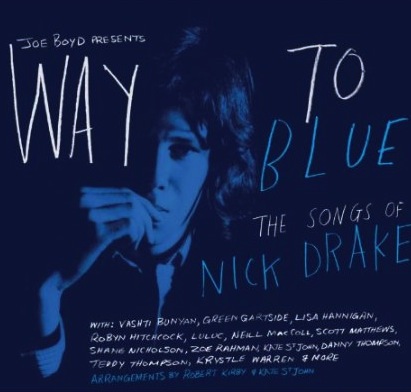

The key to Nick’s own – initially very limited – fame was the estimable Joe Boyd, the expatriate American whose career has entwined with Pink Floyd, Abba and many other high achievers. It was Boyd who brought in exemplary sidemen like Richard Thompson on guitar, bassist Danny Thompson and even the old master of cultishness himself, John Cale, weaving Drake’s self-absorbed, breathy murmur and filigree guitar arpeggios into textures of delicate string-accompanied folk and jazz.

Celebrities from Chris Martin to Kate Bush have hailed Drake’s influence, but it is Boyd who has championed his music in the marketplace, resisting the sort of tribute that would value box-office over spirit.

This new album, then, comes from the concerts the producer organised in 2010 and 2011, complete with the string arrangements of Drake’s Cambridge classmate Robert Kirby, the stalwart Danny Thompson, and a cross-generational injection of new blood. That’s Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger’s son Neil recreating Drake’s fingerpicked guitar, and Richard and Linda Thompson’s boy Teddy among a gang of guest vocalists that includes Scritti Politti’s Green Gartside and Drake’s contemporary Vashti Bunyan.

It’s a lush, confident, idiosyncratic noise the ensemble makes, too, with cor anglais, accordion, and pianist Zoe Rahman providing a sensational injection of improvisatory jazz. Somewhere beyond the stage, the sound of the concert hall audience has been virtually erased, as if to remind us that the voice which reached countless listeners long after it stopped singing was always expressing a finely-tuned inwardness. And actually, without the core of Drake’s appeal – the tension between that insular self-assurance and the fragility of the singer’s relationship with the world beyond – none of it sounds quite like Nick Drake.

So the music becomes something else; and yet in Robyn Hitchcock’s sneer on ‘Parasite’ or Krystle Warren’s near-gospel rendering of ‘Time Has Told Me’, it’s clear that a future life is possible. Which means that Way To Blue isn’t just a live CD. Exemplifying the work of Joe Boyd (and of Gabrielle Drake, who has been rigorously loyal to her brother’s legacy) it’s a fascinating and charming example of creative curatorship.