Man Ray was a multimedia artist best known for his portrait photography, yet despite his fame an often overlooked aspect of his work is his successful and progressive role as a filmmaker. Man Ray made a significant contribution to the cinema of the 1920s during rapid developments towards the establishment of art film. He transferred his pioneering methods in photography to the moving image and despite his sometimes diffident attitude toward filmmaking, his four main films remain influential and explore the artists’ lasting preoccupations with light, the kinetic, and the object. The result is a body of work that is technically innovative and visually striking.

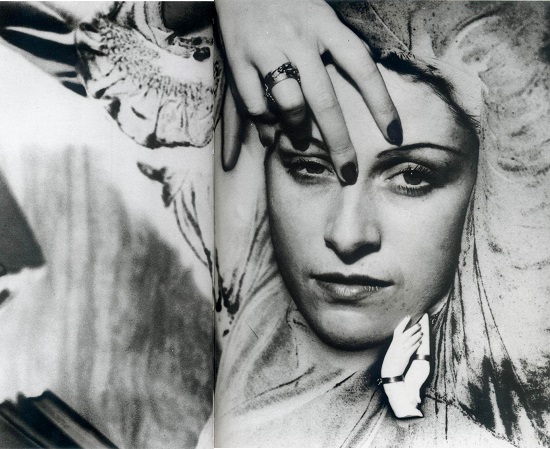

In 1921, at the age of thirty-one, Man Ray left New York for Paris. Disillusioned with New York, the shift to the then epicentre of avant garde activity was intended to rejuvenate his creativity and establish financially viable means to support his work as a painter and photographer. Immersing himself in both the Dada and Surrealist movements – one of the few artists to perform an influential role in both – Man Ray further diversified his art practice, making work in forms including photography, literature, sculpture, painting and filmmaking. His innovations were technical as well as conceptual; pioneering photographic techniques such as solarisation and the photogram, or Rayograph, as he styled it. This inventive and progressive approach imbues his work with a sense of urgency and aesthetic appeal that it retains to the present.

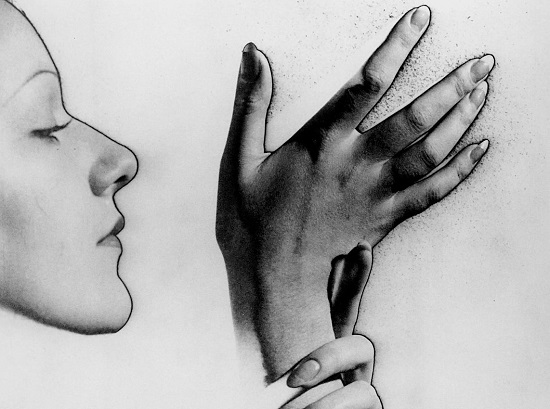

Man Ray was obsessed by objects. In his photography and films we see items combined in unusual ways, offering new perspectives on the ephemera of modern surroundings. His mode of creation and fabrication manifests as a sort of syncretic enterprise, where a number of different motifs play a role in discovering the miraculous, hidden and obscure. In choreographing scenes based on chance operations, combined with a unique sense of curation, Man Ray’s influence on objects is like that of an inflection on the voice: subtle, personal and unique. His innovative yet playful approach was founded on experimentation driven by chance and interpreted by a discerning eye.

"The characteristic of the strong image is of its being born of the spontaneous drawing together of two very distinct realities, the relations between which only the spirit has grasped… the more the relationship between these realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be, the greater its emotional power and poetic reality." – Man Ray

Ultimately, for the audience, it is with the camera that Man Ray masterfully captures the aura of these items and his human subjects, and it is the combination of innovative technique with striking content that results in a unique and diverse body of work.

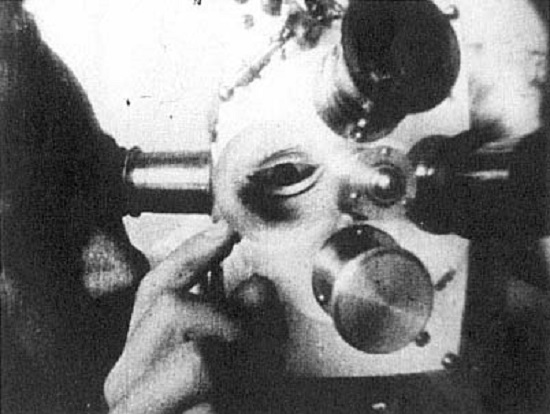

Whilst photography and painting were paramount for this multidisciplinary artist, Man Ray did enjoy a significant and worthwhile interaction with the cinema. Previous flawed attempts at filmmaking with fellow artistic innovator Marcel Duchamp, including an experiment with 3-D, did not deter the artist from continuing to engage with the medium, a medium in its infancy and on the cusp of new artistic developments. In 1923, prominent Dada figure Tristan Tzara billed a (non-existent) film by Man Ray as part of what was to be the last Dada event, The Evening of the Bearded Heart. Man Ray was forcibly inspired to complete a film for the screening. Le Retour a la Raison, or Return to Reason is the ironic title for three minutes of disassociated sequences that vivify Ray’s photography with motion. It was the first film to successfully make use of the photogram technique—discounting the failed attempts of the Futurists and the rumours that Mary Hallock-Greenewalt used celluloid directly for a colour light film to accompany her remarkable musical compositions.

Initially, Ray had scraped together a few sequences including Kiki de Montparnasse’s rotating torso, and a spiralling piece of sculpture. With barely enough for a homespun slideshow, Tzara encouraged Ray to include filmic adaptations of his Rayographs. Sprinkling photosensitive paper with pepper and shavings alongside an array of other common objects, Ray filled out the piece to a reasonable length for a short film, at least enough to impress the Dada clique who would be present at the film’s premiere. By all accounts the screening was a farcical display. Spliced together with cuts in numerous places, unsurprisingly the film repeatedly split during the screening. The unrest in the audience turned to a full-blown fight and the police were called. Something that tended to happen a lot at Dada events.

This was to be the first of four films created between 1923 and 1929, within a body of work that incorporates both Dadaist and Surrealist styles of filmmaking. The short, oblique, irrational non-narrative of Le Retour a la Raison invoked a Dada aesthetic, both conceptually and visually. Emak Bakia, Ray’s second film, incorporated sequences from his first, intercut with original scenes that err towards Surrealism, the movement Ray had migrated towards with the death of Dada in 1923. L’Etoile de Mer completed the transition to the quasi-narrative and oneiric framework that underpinned the absurd, psychologically charged films of the Surrealist movement.

After briefly abandoning film entirely in 1928, Man Ray returned to make one last film, at the request of Vicomte de Noailles, to document his art collection and château in the South of France. Les Mysteres du Chateau du De was not intended for public screening, and is thus a more personal film with a narrative thread connecting sequences from what could be an archaic yet delightful episode of Through the Keyhole. Viewing this work as a whole, there is an authorial union between the four films, yet the distinction in style and creative intent is clear.

What seems most consistent is Man Ray’s distant relationship with the medium. Whilst Tristan Tzara forced the creation of Le Retour a la Raison, the other three films were either instigated through financial persuasion, or not intended for release. As a multimedia artist, one would expect a resistance to those practices of lesser priority, but it seems there were a number of reasons for Ray’s continual dismissal of film. As a painter, filmmaking proved prohibitively expensive, especially for the uncommercial ideas he pursued. With painting, or even photography, the process was inexpensive and didn’t require immediate revenue on completion. Even modest remuneration for the most successful of Man Ray’s films, L’Etoile De Mer was not enough to convince the artist of its worth. Furthermore, Ray had no desire to be a director and didn’t want to be seen as shunning photography, his primary source of income (given that his name and address were accessible to any tourist in Paris seeking a portrait in the exotic capital). But perhaps most importantly, Man Ray was resistant to the addition of sound to film. Not only did the coming of sound involve further collaboration with technical staff (Ray preferred to work alone) it brought artistic compromise. Man Ray made the case as a visual artist that film is a purely visual medium and this important characteristic assures a distance from reality; film is not to be a documentation of life, but a poem on the rhythms of existence.

Man Ray’s artistic sensibility was very much at the heart of the avant-garde in the 1920s. Artists exclaimed the need for film to develop autonomously, without aping the tropes of theatre and literature, and were entirely enthralled by the potential for originality and innovation the cinema had to offer. Virginia Woolf was amongst them. She wrote, "anger is not merely rant and rhetoric, red faces and clenched fists. It is perhaps a black line wriggling upon a white sheet." Thus, the opportunity arose to develop a language for the dynamics of movement found in the work of Cubist painters such as Picasso and Cezanne. With Modernism came a seismic shift in notions of perception, bringing about an interest in the representation of movement and tendency toward abstraction. It’s easy to understand why these artists didn’t want to use this relatively new invention as a way of merely documenting a play.

Man Ray’s contribution to the development of art film is perhaps most evident with the cameraless sequences in Le Retour a la Raison. Sequences created by using the celluloid itself as a canvas. He was just one of many artists, primarily working with other mediums, who envisaged and realised new ways to think about and create film. Viking Eggeling and Hans Richter transferred rhythmical abstract compositions from scrolls of paper to reels of celluloid. Walther Ruttmann presented animations that were majestic and musical in their silence. Rene Clair was particularly outspoken: "In an era when for some among us fiction and drama seemed to belong to a worm-eaten age whose rubbish was being hauled away by the Dada moving men… the cinema was seen as the medium of expression that was the newest and the least compromised by its past – in a word, the most revolutionary."

The films borne out of the early avant garde of the 1920s were conceived and created by artists, rather than dedicated filmmakers. To establish itself and achieve autonomy from the other arts, the progressive contingency within cinema embraced the lively, liberated spirit of post-cubist art movements, encompassing ideas of movement, abstraction and the ineffable. Artists like Man Ray were vital for this progressive step; freely experimenting with the medium, with a commitment to the fullness of art as a whole. As Man Ray proposed, "perhaps the final goal of the artist is a confusion of all the arts, as things merge in real life." With this sprawling sensibility, Man Ray was perfectly placed to steward film in an innovative direction, amongst a swathe of artists who were also committed to finding new ways to bring ideas to life, facilitating a true and pure expression of aesthetic thought.

Movement in Light is a series of screenings taking place at the National Portrait Gallery that explore the work of Man Ray and his contemporaries, including Walther Ruttmann, Hans Richter, Stan Brakhage and Lis Rhodes, with live accompaniment from Portland-based Ilyas Ahmed and arts collective Collectress, in addition to new works from contemporary artists.

The Art of Movement (28/03) – http://tinyurl.com/ax85rsd

Pure Figures in Motion (12/04) – http://tinyurl.com/a3sp6b8

A Contemporary Expression (18/04) – http://tinyurl.com/ayauoa6