The Archer shot by John Rowlands

The first things you see are 500 oranges, being painstakingly arranged into a square Gilbert & George floor display by workers in blue latex gloves. The first thing you hear, on your radio headset, is a John Cage piano piece. The first thing you think is: um, have I walked into the wrong room?

That, says the V&A’s Victoria Broackes, co-curator of David Bowie Is, struggling to make herself heard above last-minute drilling and hammering, is quite deliberate: “The intention is to immediately disorient the visitor, so they’re already thinking about the way David Bowie operates in the context of other art, from the moment they walk in from the street.”

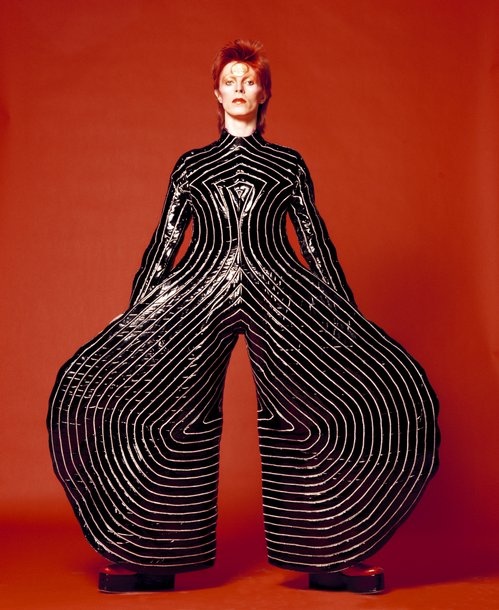

The first actual communique from Bowie, inscribed on the wall above the actual huge-legged Kansai Yamamoto trouser suit from that famous Masayoshi Sukita photo shoot (you do a lot of “Oh my god, it’s the actual…” as you walk around David Bowie Is), is a quote from a 1995 interview which runs: “All art is unstable. Its meaning is not necessarily that implied by the author. There is no authoritative voice. There are only multiple readings.”

It’s a statement which sets the tone for the gently relativist, non-didactic approach of the exhibition as a whole. Rather than telling you what to think, David Bowie Is succeeds in being endlessly thought-provoking by essentially asking: what does all of this mean to YOU?

Instead of a simple timeline, or boring parade of costumes and glass boxes, the exhibition is as thematic and multi-disciplinary as was promised at the press conference last year, touching on innumerable apposite influences (JG Ballard, Andy Warhol, Fritz Lang, the moon landings, and so on). And, fittingly for an artist so obsessed with the visual image, it looks incredible. The visual aesthetic has been achieved by going straight to the source. “For the design,” says Broackes, “we’ve taken our cues from things like the Station To Station tour and the Rainbow Theatre show.”

We start, though, among the Buddleia-choked bombsites of post-war London, with the cultural detritus that would have surrounded the young David Jones (ration books, a poster for a Joe Orton play, a copy of Colin MacInnes’ Absolute Beginners etc), and a 3D, projected imagination of his teenage bedroom, as we hear the man himself on our headsets, reminiscing about his mindset in those formative years. “That was the big struggle: wondering if I should try and be me, or make up some people and I’d be them. Being someone else is much easier.”

We witness Jones’ first faltering stabs at fame, fronting a lobby group called The Society For Prevention Of Cruelty To Long Haired Men at just 17, and in bands such as Dave And The Bowmen (for whom, tellingly, he was as fixated with designing hand-drawn costumes as with writing songs). There’s a letter from Bowie’s first manager, Ralph Horton, to the man who would become his second, Ken Pitt, containing the historic news “I have now changed Davie’s name to David Bowie”. There’s a poster for an early solo appearance at the Royal Festival Hall, at the bottom of a bill headed by Tyrannosaurus Rex, with ‘Vibrations by John Peel’. And there’s a hilariously earnest early Decca press release: “He is 19, slim, fair, blue-eyed, and impatient to release his enormous store of pent-up talent…” (somewhat smoothing over the truth about his eyes).

Suddenly we’re into the untouchable golden years. We’re confronted with the iconic “Starman” costume (conceived by Bowie as “Ultraviolence in Liberty fabrics”) and a display about its life-changing TOTP performance, with Spandau Ballet’s Gary Kemp speaking for the generation who were never quite the same again. There’s plenty of Ziggy Stardust material, of course, including Bowie’s hand-written thematic synopsis, and Bernard Falk’s 1973 Nationwide report on Ziggy-mania (“this bizarre, self-constructed freak”).

There’s a whole room on the Berlin era, containing, among other things, a genuinely excellent oil painting of Iggy Pop by Bowie, and a less impressive doodle on a ripped-open Gitanes packet. And there’s the giant triangular vinyl tuxedo worn on Saturday Night Live in 1979 (and later adopted by his backing singer that night, Klaus Nomi) which, we learn, was inspired by the Constructivist artwork and costumes Sonia Delaunay had created for Tristan Tzara’s The Gas Heart. On a less highbrow level, we also see the actual pink poodle toy from the same SNL clip, with a working TV wedged in its mouth.

The main showpiece spectacular, a high-ceilinged room containing giant gauze edifices with the proportions of a photographic contact sheet onto which footage of the Ziggy, Diamond Dogs and other tours are projected (with the relevant mannequins spotlit behind them), is still going through its final adjustments on the day I’m given my sneak preview, two days before the official press viewing. Men with furrowed brows hunch over laptops, fine-tuning the Live Aid ‘“Heroes”’ clip. If it lives up to the billing, it ought to be mindblowing.

Other notable items? Forgive me if I descend into list-making here, but it’s hard to avoid. There’s the storyboard for his never-made dystopian Hunger City film (a proposed companion to the Diamond Dogs album). There’s a look at his ‘Verbasizer’ software (a hi-tech version of the Burroughsian cut-up technique used during the 1970s). There are work-in-progress early drafts of The Next Day artwork (interestingly, they experimented with blanking out Pin-Ups and Aladdin Sane before settling on "Heroes"). There’s a piece of paper containing Bowie’s clothes measurements (including, amazingly, a 26½ inch waist, which really becomes apparent when you see the sky-blue ‘Life On Mars’ suit side-on.) There are scribbled musical ideas for 2003’s Heathen, such as “Piece based on chanson’ and “Try ‘jungle’ underneath ‘Beach Boys’”. There’s the carefully-inked sheet music for ‘Fame’, and the actual crystal ball from Labyrinth. As Victoria Broackes points out, many of these items appear to attain the status of “holy relics”, a notable example being a piece of tissue blotted with Bowie’s lipstick from 1974 (glam rock’s very own Turin Shroud). On more than one display cabinet I see a Post-It note reading “Needs An Alarm”, and think to myself: "Damn right, it does."

Bowie nerds will enjoy examining lyrical first drafts in his handwritten exercise books, paying particular attention to the crossings-out in order to trace Bowie’s thought-processes, and imagine what might have been. On one page, there’s an intriguing list of mostly-unfamiliar songtitles. You don’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to figure out that ‘We Should Be On By Now’ probably morphed into ‘Time’, but give yourself a pat on the back if you know what became of ‘Miss Peculiar’, ‘Right On Mother’, ‘Shadow Man’, ‘Rupert The Riley’, ‘Hole In The Ground’ and ‘Here She Comes’ (some of which even ultra-comprehensive Bowie fansite Teenage Wildlife doesn’t know about, at the time of writing).

Seriously hardcore nutters will doubtless be ringing Ken Pitt’s decades-defunct phone number, scrawled in pencil on the sheet music for ‘Space Oddity’, just to see who answers. My own sad-bastard moment came in the mocked-up recording studio vocal booth, when I saw a handwritten budget – without any explanatory label – of £145 for a session on Wednesday 14th July (no year given). Yes, I went home and spent an undue amount of time on Google and Wikipedia. Yes, I narrowed it down to either Hunky Dory or Low.

Design by Kansai Yamamoto. Photograph by Masayoshi Sukita

For all the spoilers I’ve given you, I’ve scarcely scratched the surface. What becomes clear is that, amazingly, even through the chaotic years when “a few lines and a handful of ‘luudes” constituted breakfast, Bowie has kept EVERYTHING. And the V&A couldn’t have done a better job in skilfully picking out the best bits: short of a fridge full of bottles of Bowie-piss labelled ‘1975’, it’s difficult to imagine how this collection could have been improved. And this isn’t a quick 45-minute job. You’re going to want to arrive early, and spend all day. You’ll leave with your brain buzzing with ideas, high on a hit of pure distilled genius.

Demand has been unprecedented: 38,000 pre-sales, which is ten times anything the V&A has done before. But Victoria Broackes is at pains to point out that there will always be tickets available on the day. “We will never sell it out, because we know people will have travelled across the world to see it and we don’t want them to be disappointed.”

After the London run has ended in August, the plan is for David Bowie Is to tour the globe. Already, negotiations to take it to Paris, Berlin, Sao Paulo, Australia and Japan are at an advanced stage. But if Madrid can have a permanent Picasso museum and Amsterdam a Van Gogh one, doesn’t London deserve a National Museum Of Bowie? “That would be nice…” For now, the hugely satisfying David Bowie Is book – including essays from Camille Paglia, Mark Kermode, Howard Goodall, Jon Savage and Christopher Frayling, as well as a massive array of photographs – will have to remain the next best thing.

So, it turns out that the most thrilling major musical event of 2013 is a museum exhibition. There will be many who find that fact a depressing indictment of the stagnation of modern culture. But that’s not Bowie’s fault, nor is it the V&A’s. David Bowie Is, as ever, just waiting for the rest of the rock & roll world to catch up.

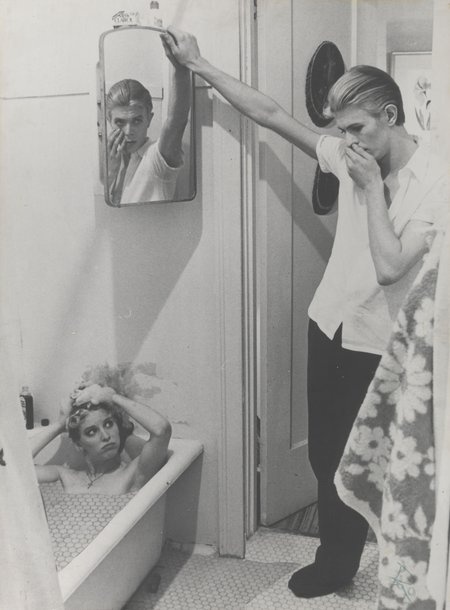

Film still by David James, design by Bowie

David Bowie Is opens on Saturday March 23 and runs until August 11. Tickets are on sale now