The motorik spirit is alive and well in Finland

Siinai have been on our radar for a while now, most recently for last year’s collaborative album with Wolf Parade/Moonface’s Spencer Krug, Heartbreaking Bravery. Their previous album, 2011’s Olympic Games, is an expansive slowgaze epic: taking the heroic spirit of the titular event as its steer, the album operates almost entirely in vast swathes of synth beds and rolling bass, working up to rhythmic breaking points that release cyclical motorik repetitions.

On record, the album’s almost constant triumph-over-adversity motif verges on being a little wearing; there are only so many times you can bear witness to the the sonic equivalent of the 5000 metres. Live, though, the sound is transformative. The band play two dates at Eurosonic, the first of which is in the Grand Theatre, a beautiful, cathedral-like space. In this setting, Siinai flourish. They fade in with the 17-minute segued opener ‘Anthem 1 & 2’ (have a listen below) – there’s Vangelis lingering in the the synthetic horns that blart out and sprawl, before cymbals flare and crushing drums crash through. Elsewhere, ‘Anthem 3’s tremulous piano and basking choir is a highlight, again amplified by the surroundings, with the treble-heavy keys reverberating against the theatre’s open-brick surfaces. There’s a sense of event – green spotlights, the drummer hopping over his kit to play it from the front – but there’s no hint of pretence; this is pure concentration and sonic moment.

All the more impressive when it turns out that the debut album came out of some exploratory jam sessions and was partly recorded on a 20 Euro mic. The Olympic theme, though, wasn’t a reflection of the band being avid sports watchers, says guitarist Risto Joensuu: “Some of the jams we had, it was like ‘shit, this sounds like a slow-motion running soundtrack’ or something that you would listen to in an Olympic ceremony.

While the band’s reasoning is slightly less immediate for the heavy krautrock influence, they see it as a sound they can inherently tap into – as bassist Matti Ahopelto says: “Krautrock came after the war, people wanted to hear something new; we obviously don’t have the war to reflect on, but there is something familiar about it!” Adds Risto: “It’s hard to say, but maybe this German stuff from the 70s feels more natural to us than American music – maybe we don’t how to play American music that well, but we feel more connected… it’s a European thing.”

While there are also clatterings of krautrock in fellow Finns Death Hawks’ sound, their debut album from last year, Death & Decay, is a broader classic rock survey. While on paper the idea of yet another raw-riffin’, Hammond-toting five-piece might seem doubtful, the LP reveals itself to be anything but. All the tracks are wrought under the aegis of the apocalypse, with Death Hawks invariably choosing their lyrical themes around the dark and stormy – sample track names: ‘How Dark Was The Land’ and ‘Death Has No Reprieve’ – but rather than soundtracking this with wearisome wank-off wig outs, their cuts display an impressive instrumental proficiency and genre-voracious appetite. The brush sweeps of Neil Young’s ‘Harvest’ resurface in ‘The Beast’, prefacing a gorgeous chorus vocal melody dressed with the kind of deft organ augmentation of Wilco’s ‘Sky Blue Sky’. Elsewhere, ‘Roamin’ Baby Blues’ is rabid, sub-two minute country-skiffle, while LP highlight ‘Shining’ is pure motorik rhythm and riff – have a listen below:

Temples are the new high priests of psychedelia

Christ knows the last thing anyone needs is another 60s revivalist quartet, yet cutting a path through the paisley jungle are Kettering’s Temples, a recent signing to Heavenly who have a particularly new single in the form of last year’s ‘Shelter Song’. That track’s ace, angular 12-string riff, and its simple pleasures lyrics, embellished with harps, suggest that we might have something brilliant to adorn with the “60s psych” tags, and steer ourselves up the Tame Impala delta and out of the ocean of crap surf-rockism.

The Temples that appear in De Spieghel tonight sound more direct than on record, partly due to the core duo of James Bagshaw and Thomas Walmsley being expanded to a four-piece live. The expertly-cultivated vintage sonics of ‘Shelter Song’ and its b-side ‘The Golden Throne’ – the distance of the vocals, the roll of the snare, the slightly gritty distortion in the strings’ scythe – cannot be easily recaptured live. But it’s still the sound of a band whose songs are fine-tuned and performances hard-wired. There’s gnarly organ, deftly deployed, and Walmsley’s bass lines are, almost unexpectedly, a prominent force, melodic and propulsive. The on-record riffs audibly want to tear away and do more, and Bagshaw’s guitar work occasionally does so here: there’s no speaker cone-serrating Kinks-esque soloing, more artful restraint and the odd blues growl. The performance the band turn in, battling against the ponderous indifference of the assembled industry crowd, is muscular and tight, an exciting presage to what’s going to come from their first full-length.

The next night, it’s the turn of hyped Dutchman Jacco Gardner to hoist psych’s motley mast. Playing in Huis De Beurs, a venue fittingly resplendent in 60s living room decor, though, tempered with the blood red walls lingering in the dingy gloom, the place has a curiously baroque feel, Gardner’s psych-pop is the acoustic cosmic day-tripper to Temples’ electric glam-stomp. Beyond any threat of pastiche, his band build on the sonic template of the psychedelic pop song, drawing in echoed backing vocals and unexpected key changes, creating a sound, live at least, that’s oddly similar to Animal Collective, if they’d gone acoustic and were still good. Rivulets of guitar lines run from Gardner’s guitar like Arthur Lee’s, and while his voice does have the sound of perennial touchstone Syd Barrett, there’s Andy Partridge at his most eccentric there too. His debut album, the recently-released Cabinet Of Curiosities takes the lead most strongly from the former two, a carefully-constructed mainly acoustic mix of soaring Mellotron lines, astral vocals and fantastical lyricism. Crucially, and similarly to Temples, Gardner has forged genuine songs, a fact that live, with the Hammond and harpsichord fringing the tracks, is brought into clearer focus. From his home — the “Shadow Shoppe Studio” — near Amsterdam, Gardner makes something that, while hugely indebted to the past, is wrought with such palpable skill and love that it makes existing in his self-contained universe a beguiling proposition.

Feeling skweemish? Try some Huoratron

From what we’d seen of him before, be it the line drawing depicting his melting flesh departing his skull and eyes seeping black liquid or his video for ‘Corporate Occult’, tQ was fully expecting Huoratron to be a towering bear-like figure, one who conducted Richter scale-bothering sub-bass tests in some cavern up Mount Yllästunturi, occasionally venturing out to bedevil David Guetta and his ilk, leaving a trail of decimated laptops in his wake.

While some of the above may be true (he’s certainly a tall man), Huoratron, otherwise known as Aku Raski, is also a charming, articulate advocate of blunt-force techno, and one whose presence is sweetly at odds with the Douwe Egberts coffee shop in which our interview takes place.

His brand of electronics is a fearsome one, taking harsh, grinding beats for its foundation and then blasting them with baseball bat-to-the-head interpolations on his last album, 2011’s Cryptocracy.

The root of Huoratron’s noisemongering lies in the fact that his first musical output was playing bass in a hardcore punk – “we started with a lot of cellars that smelled like mould” – though after deciding that the instrument wasn’t for him “and a lot of eye and throat infections later”, he started experimenting with electronics. “My friend hand-built a sampler that ran straight into my computer and I started sampling bass riffs and added those to weird industrial beats or whatever. Gameboys came later when I figured out that the console had a musical output that I figured out sounded like it was driven through a fuzz pedal: fucking brilliant! You cannot make music that doesn’t contain a fuzz pedal? That’s for me!” No Super Mario Bros-inspired bleeping for him, though – “it was too happy, happy, joy, joy, so I absolutely wanted to turn this around and take out the most evil sound that I could from the machine…”

This viscerality, though, is matched to a scrupulous quality control ethic. “I’m not one of those guys who is composing on aeroplanes or releasing one track a week. I’m probably one of the most anal guys you know in terms of how far I go into the frequencies, dynamics, and, of course, that, in a sense, takes time.” He terms the churn-’em-out school of dance music “fast food stuff”, and counters it with a slow distillation process, with the tracks coming into being over a number of iterations. “There’s a huge amount of details put into stuff,” he says, “it’s also the final iteration that is the version that’s been standing there, on the teeth of time, through the production process – it’s kind of like natural selection, a lot of stuff is made and then thrown out.”

This arch-perfectionism transfers to the gig, too. In the back-room of the Huize Maas, a far cry from where Dutch Uncles had been plying their kinetic art-pop the night before, Raski deploys his tracks with clinical skill, tracks like ‘Bug Party’ and ‘Transcendence’ leaving the bar nothing but a heaving sweat-repository. Sirens, fried 8-bit stutters, rapidfire filters and industrial-speed bass kicks coalesce and wreak vengeance on one another. Through all this sonic punishment, Raski makes what he calls his “silent handshake” with the audience, an appreciative mutual headnod to the sea of electronic ruination by which they’re surrounded.

A fellow Finnish electronics man plying his trade was Mesak, trailblazer for the ‘skwee’ genre. What’s skwee? Assemble a range of vintage analog equipment and ‘skwee-ze’ out the best of them onto samples and chiptune glitches, and there you have it, a highly-caffeinated homegrown electronic genre. It takes some of that fiercely-varied sonic bric-a-brac that Huoratron favours, and pushes it along the line towards Flying Lotus-esque IDM, though less freeform for being placed within a strict beat. Tatu Metsätähti, aka Mesak, is one of its pioneers. Having also begun experimenting with composition on a Gameboy as a teenager, he’s gone on to prolifically release tracks and EPs, mostly through his label Harmönia, co-founded with skwee exponent Randy Barracuda. While some Mesak releases, such as last year’s Holtiton mini-album have shades of Ford & Lopatin’s synth-pop in the synthetic tom rolls and sheeny pads, skwee is amorphous, grown out of live collaborations, which are then released by the label, such as the ‘Ya Tosiba: Mad Barber’ 12” with Lebanese DJ Zuzu.

Pertti Kurikan Nimipäivät slay all comers

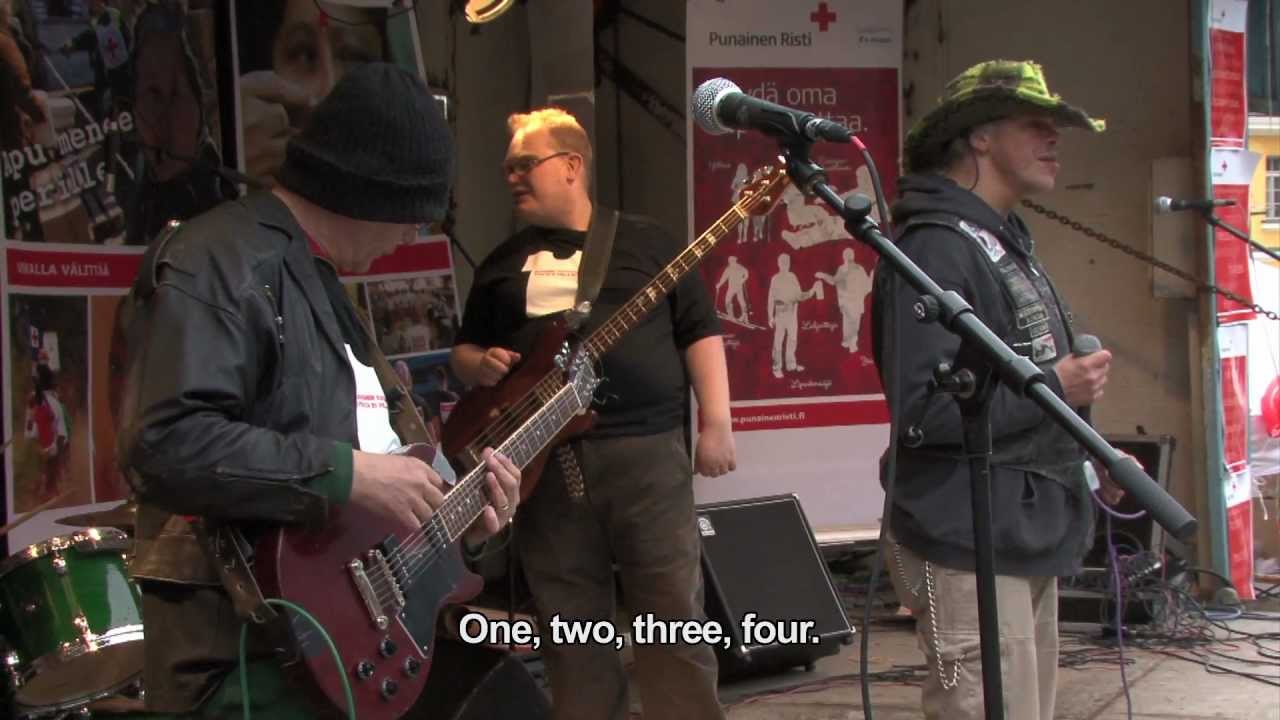

Dealing out one of the best shows at the festival were Pertti Kurikan Nimipäivät, a four-piece punk band from Finland, all of whose members are mentally handicapped. Last year, they were featured of the documentary The Punk Syndrome, which followed them as they recorded a single and hit the road – have a watch of the trailer below:

As the film shows, the band’s gigs are, in short, phenomenal: arriving onstage at Vindicat, Groningen’s grottiest venue, the band proceeded to power through a set of straight-ahead three-minute shards of vitriolic punk, delivered with sheer conviction and unbridled feeling. Frontman Kari Aalto stands almost motionless at the front of the stage, delivering his lyrics in a determined speak-sung vocal, while Sami Helle commands the band from his bass, holding down the entire band. There’s no hint of posturing, no archness to the image; the music is just fervently drawn from the heart.

Halfway through the set Aalto unbuckles his belt and takes off his jeans to reveal black and white striped long johns. The crowd, already the most enthusiastic of Eurosonic, go through the roof. While Aalto stands watching what must be the best all-time reaction to a pair of stripey tights, his band kick in again, unbothered by their frontman’s sartorial divesting.

The set closer ends up forging a moment of magnificent power: the chorus line’s refrain of ‘fuck the world’ becomes one soaring, ascendant hook from which the band’s churning rhythms reach breaking point. It’s not long before Aalto is on the floor, knees pulled up in foetal position, howling “fuck the world”. The band come to a close, but the bass drum’s incessant thump remains. Gradually, Toni Välitalo rebuilds the beat, adding in tom rolls and cymbal crashes until, one-by-one, his bandmates rejoin. Now, everything is doubled. Pertti Kurikka’s power chord grind is now a rapid thrash, while the drums and bass building towards cataclysm, while Aalto’s screech resurfaces. This time, audience members sing with him and raise fists in time with the words. The pain and frustration with which the song is wrought is at once shared by the audience, and, perhaps, momentarily dissipated.

10 303s + 1 707 x Koskenkorva Viina = sonic perfection

Providing what would turn out to be the highlight of the festival, Acid Symphony Orchestra inaugurate the final night in Groningen. The brainchild of Finnish house doyen Jori Hulkkonen, ASO was dreamt up as a live, improvisational collective of an ‘orchestra’ of 10 Roland TB-303 bass synthesisers with Hulkonen ‘conducting’, simultaneously mixing the collected feeds coming from the synths and operating a TR-707 drum machine. A semi-circle of chairs adorn the stage of the Stadsschouwburg, Groningen’s beautiful 19th-century city theatre, before the performers emerge, decked out in orchestrally-appropriate suits, followed by Hulkkonen, resplendent in conductor’s tails.

What begins is a 45-minute microcosm of performances that I’m later told by Huoratron – one of the orchestra’s members – tend to last upwards of three hours, accompanied by a pre-show ritual of “four litres of vodka, and I’m not fucking kidding”.

First we get broad bass waves spilling out over the audience, shapeless, phasing sounds from the individual 303s. Gradually, things begin to meld together, uniting as the synth lines oscillate into one another. A bottle of Koskenkorva Viina, bracing Finnish alcohol, is passed around, with each member of the collective taking a swig and passing it on.

At first there are only sparse four-on-the-floor bass thumps with the occasional cymbal flare. Then, there’s a momentary pause in the orchestra’s synth movement, before the drum machine comes into its own. Hulkkonen adds in different sounds, subtly shifting the rhythmic emphasis with each addition – he moves through a jagged new wave beat, then r’n’b, then a snare-heavy backbeat, through to house and then into a pure techno banger.

The consummate ease with which Hulkkonen rifles through the genres reflects a long-term obsession with electronics. He’s plied house music under numerous different guises – Third Culture, Processory, SCT, and perhaps most notably as Zyntherius, collaborating with Tiga for their cover of ‘Sunglasses At Night’ – and Hulkkonen is also at Eurosonic as part of the synth-pop duo Sin Cos Tan. Talking about his formative musical experiences in Kemi in west Finland, he says: “In the early 80s, Finnish radio was horrible – there was maybe one hour a day of pop music. Fortunately for me, I was living very close to the Swedish border, so I had Swedish TV and radio and they were a couple of decades ahead in terms of what pop culture could be. It was through this that I discovered New Wave, synth-pop and Italo. The sound of the synthesisers was thought to be somehow futuristic and the music was, in a way, escapism, with the futuristic music like Italdisco, that was the perfect thing that I needed.

While he describes the ASO as “a curious little thing”, it’s also very decidedly a ‘live’, not recorded, event. “I had the idea for a long time, and I’ve always liked the avant-garde and experimental electronic music. At the same time, when people perform live nowadays with a lot of electronic music it’s just like laptop, which I just find boring. So the idea is to do something that you actually have to experience, as opposed to being able to download it.

“I write all the lines and send them out to the guys – on the flight here, everybody was programming. The whole structure and is musically well thought out, but the actual show is kind of improvised – it’s not that far from jazz. It’s not like it’s musically the most advanced thing, but it’s a different aspect because no one else is doing that, it sounds fresh.”

Back in the performance, Hulkkonen’s Hyde takes over, and he jabs at the 707 with free abandon. Incredibly, rather than devolving into scattershot house cataclysm, the sound tightens, becoming an all-consuming amalgam of warped synth lines and crashing, ferocious beats, entirely enveloping the Stadsschouwburg. All the more incredible considering that this is being created on the spot, in real time. In short, vast brilliance distilled down into 45 minutes of captivating machine manipulation.