Hello, my name’s John and I’m an alcoholic.

I didn’t want to do this chair when I woke up this morning. I’d been putting off thinking about it for days but then I played a new record and it gave me an idea. I hope it makes sense but please bear with me while I try and articulate what I mean.

I remember when I first came into these rooms five years ago, the person who was chairing the meeting, sitting behind the table like I am now, said: "If you’re less than 24 hours sober we ask that you don’t share, just pay close attention to things said that you identify with and don’t worry too much about the things that you don’t."

I had a fair idea that I’d hear some bracing things. Like Chapter Three from The Big Book says: "Most of us have been unwilling to admit we were real alcoholics. No person likes to think he is mentally different from his fellows. Therefore it is not surprising that our drinking careers have been characterised by countless vain attempts to prove we could drink like other people. The idea that somehow, someday he will control and enjoy his drinking is the great obsession of every abnormal drinker. The persistence of this illusion is astonishing. Many pursue it into the gates of insanity or death."

Insanity and death. Those were two of the things I had an inkling I was going to hear about when I first came here to the rooms.

Then there were some other things that didn’t surprise me when I did hear about them: violent dads, insane mothers, trouble at school, unemployment, prison, mad houses, fights, regretful sex, unplanned pregnancies, regretful abortions, drunk driving, car accidents, the death of friends, depression, suicide, illness and hospitals. Cradle to the grave drinking.

One of the things I didn’t know I’d hear about though was the quest for beauty, a struggle to achieve aesthetic perfection in an imperfect world. For me, every morning I woke up, the world was too ugly to face. There was dirt, horror and disfigurement everywhere I looked. But after one stiff drink I could leave the house; after two drinks the fear started lifting and then after the third drink I’d feel like an artist. Or to be more precise, I would see the world through the eyes of an artist. And after five drinks, well, take your pick. On a good day I felt like Picasso. But there were all kinds of days. Imagine being Gustav Klimt in Hull, the golden light of the low winter sun at 3pm in the afternoon radiating along the avenues. Imagine being Walter Sickert in Manchester, the violent brown and black smudges radiating from your feet and along canal tow paths. Imagine being Vincent Van Goch in St Helens. That is something close to victory, something close to beating death.

They laughed at me and called me a piss artist. And how right they were. I was an aesthete with a broken nose in a stained shirt and inside out boxer shorts, drinking the world beautiful.

Thus protected you can see the sublime in the augury of fried chicken bones and tomato sauce cast upon the upper deck floor of a bus. You can divine a narrative among the finger-drawn doodles on the misted windows. You can feel your destiny in hundreds of individual condensation droplets on the glass turning red, then amber, then green.

Everything that you’d worried about a few hours previously… Where will I get the money from? What if he beats me up? Am I seriously ill? Am I dying? Have I got cancer? What will she say when I finally get home a week late? Will she cry when we eventually go to bed together? Will she pack her things and leave the next day? How near is death? What will it be like? Will I scream and cry? What is it like to die? And now, after some drinks, there is just the sweet sensation of your life passing you by with no struggle and no fuss. The rope slides through your fingers with no friction, just warmth as a balloon rises higher and higher out of sight. I have bottles and bottles and bottles and my phone is out of credit. A Mark Rothko night. A Jackson Pollock night.

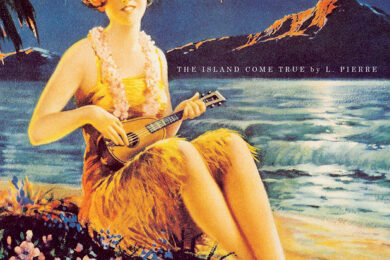

And I’d forgotten all this until I heard some music this morning. I have a new album, The Island Come True by a man called Lucky. An ironic name maybe? A drinker’s name for sure. I have another album by him as well called Touchpool. He has two others I believe but I haven’t heard them. And this music speaks to me about alcoholism.

I don’t think Lucky is an alcoholic, not a jakey, not a tramp, not an urban camper, not even a barfly or an off license gargoyle but I’ll bet you money he’s felt a great thirst in his life. I’ll bet you any money he has looked at life through the eyes of an artist at 4pm, in saloon bars, in lounge bars, on buses, in cabs, in rented flats with the thin, cheap curtains drawn during daylight hours. With laughing women. With crying women.

He makes holiday music for people who don’t go on holiday. Why would you go on holiday when you could just get a bottle of ginger beer to go with your vodka and turn on the fairy lights around the cocktail cabinet in the front room? With the constant drip feed of alcohol your entire existence becomes jaunt-like.

I don’t drink any more but when I drank. Oh boys, when I drank, I used to make myself a Samoan Fog Cutter in a tall glass with ice and listen to his song ‘Jim Dodge Dines At The Penguin Café’. And I’d wear my favourite Hawaiian shirt. Maybe turn the thermostat up a little. Put some ice in container shaped like a pineapple. Dance indoors with my lady. The ice clinking in my glass sounded like the breeze blowing a yacht’s rigging and rope against the mast.

And I know it’s not just me who feels like this.

There was a fantastic advert in the 1980s that opened with a camera panning across a tropical lagoon while a narrator said: "Peckham, on a wet Saturday afternoon." Then the film cut to a brightly coloured parrot: "Next door’s budgie." The next bit was pretty weird – pretty fucked up. It showed a sultry young woman looking sexually provocative on the beach as the voice over continued: "Auntie Beryl." The next shot was of sophisticated looking rich people in white linen clothes sipping cocktails before running down a jetty to get into a speedboat lit by an unnaturally swollen full moon: "The Dog & Duck, down the high street… Catching the last bus home…" All of which was the set up to the emphatically delivered punch line: "If you’re drinking Bacardi."

You’d never be able to screen an alcohol advert like this now… which is wrong because it’s the only truthful drink commercial that’s ever been made.

Lucky’s album speaks to me of the eternal holiday of the alcoholic. Once you create as much distance from your everyday life as you naturally have from orange tinted Polaroids of childhood caravan trips or stays in seaside hotels and Super 8 film reels of school sports days, then you start to experience your quotidian life like it’s the sun bleached memory of a happy event. You feel nostalgia and warmth for boring events that are unfolding right in front of you. You feel wistful about experiences that most people would find barbaric or gauche or unremarkable. You experience the epic, the heart-warming and the hilarious in post office and supermarket queues. You develop permanently rose-tinted glasses.

But there’s no getting away from it, after a while the strategy starts failing. You start seeing everything through the eyes of Francis Bacon, through the eyes of Edvard Munch, through the eyes of H. R. Giger…

This is Lucky’s fourth album, after a break of several years, and his strategy has changed. All of this music is made from tapes, samples, loops, found sounds, field recordings. The beauty is more fragile, more ephemeral. Melancholy, sadness and even depression are seeping in at the edges.

At the outset, seagulls soar and caw as rigging and rope snaps against mast in some unnamed harbour. A simple three note violin refrain loops as the tide rises and falls. The patina of dust on his old records is a buffer between the listener and the harshness of reality. The fact that most of these records were at one time popular, and exist in the public domain, add to the comfort to be gained…

Even though this is the music of ‘true’ sight becoming occluded, it made me think of the neurologist Oliver Sacks who tells of blind men given the gift of eyesight late in life thanks to improvements in surgery and how it does little to improve their quality of life. The anguish of Agnosia – Molyneux’s Problem – often means that visual information is too much of an overload to process when it arrives unexpectedly in adult life. The sufferer often continues to act as if blind because to try and make sense of what they can ‘see’ is too difficult, too painful, too distressing. But even if such a person learns to interpret what they ‘see’, the world can appear less idealised than they had imagined. Their environment is not clean and faces are not beautiful, they see things that we simply choose not to talk about for the first time. People who learn to see late in life often turn to suicide or fall into ill health and die not long after vision returns. Just pick up a bottle. It is a cure for what offends your eye. Pluck the cork from the bottle.

On the song ‘Harmonic Avenger’ various fine strands of easy listening are combined to provide very uneasy music. Grand piano chords echo across a winter garden. Rachmaninov’s ‘Prelude In C Sharp Minor’ if I’m not mistaken. Polynesian maidens hum a counter melody. A boulevardier plays something similar on a battered accordion. But when the descending strings hit, it is too much to hope that a fourth element will slot comfortably in place. The effect is that of the caustic clash between the diegetic music playing on a radio in a film when it rubs sourly against the extra-diegetic strings on the soundtrack. The character may well be listening to sweet pop music or soothing classical but only you, the viewer, have the intimation that something is awry.

Elsewhere loops from vintage children’s TV shows, wind up music boxes, children humming simple refrains, orchestras tuning up, the chirrup of insect life and old hypnotism records, slide in and out of the mix.

And while, no doubt, this will remind some people of music that comes out on the Ghost Box label (perhaps even in a negative way, if they have very regimented and codified views on how music in specific genres – in this case hauntology – should operate), for me, this isn’t really that important. ‘The Grief Does Not Speak’ (and all of the excellent bonus material that comes with the vinyl version), reminds me of another artist, The Caretaker. Again, maybe a lot of people will disagree. They say his music is about the loss of memory, of amnesia, dementia and Alzheimer’s. And even though it probably is, metaphorically speaking, literally this music is about the terrifyingly deleterious effects of alcohol on the brain; of a never ending round of getting clattered night after night and the fragile world of half memories and half-truths you then enter. There is beauty of sorts in this world but it’s the beauty of a finely crocheted shawl… it’s less substance than it is void. You can only define this ephemeral radiance by the holes and by the absences.

When I was a kid my parents told me a story. Two devils manufactured a mirror in Hell which rendered anyone who looked into it unbearably ugly and deformed. They flew up to Heaven to trick God into looking into it but when confronted with his beauty, it shattered into a million pieces and rained down to Earth. A girl standing below was looking up at the stars when a splinter fell into her eye, rendering everything she saw for the rest of her life horrific. The Island Come True is the act of staring at what looks like glitter gently falling from the stars towards you.

And that’s all I’ve got to say this morning. Time to open the meeting up to the room.