Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

Between her two most famous roles, Nico produced her best work. Initially she was cast as the Teutonic chanteuse, who beautified the Velvets’ trash aesthetic, singing three songs on their landmark debut and providing a visual contrast/magnet to the black-clad urchins. Then there’s the protracted rock & roll suicide of her latter days, the wilderness years chronicled by James Young in Songs They Never Play On The Radio, a warts-and-all account of life in her band, equal parts bathos and pathos. Somewhere in between these two incarnations, the model/actor/singer produced three albums, a triptych without parallel in the rock canon. 1968’s The Marble Index, 1970’s Desertshore & 1974’s The End didn’t just defy popular music’s conventions, they ditched them altogether. Conceived in a period that biographers tend to barely probe (1995’s Icon documentary only offered a cursory glance), the liminal drift of these years only emphasizes the music’s amorphous moorings and lack of precedent.

Biography and Nico are uneasy bedfellows. In fact, navigating one’s way through her life, as with so many of the VU/Warhol crowd, amounts to a Kane- like labyrinth of rumour and falsehood (“The story is telling a true lie,” as she sang on ‘Evening Of Light’). She was born Christa Päffgen to Yugoslav and Spanish parents in either Budapest or Cologne. Reports of her birth date vary from 1938 to 1943 but the former is most likely. Her father died during the second world war, probably exterminated by the Nazis after sustaining a head wound injury that would have rendered him useless to the Third Reich (there’s some suggestion that he was a Jewish spy). At the age of 15 or 16, Christa was encouraged by the couturier Oestergaard to take up modelling. She was then christened Nico by photographer Herbert Tobias, after his former lover Nikos Papatakis. After stints in Paris with Coco Chanel and Vogue, she played “Herself” in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960) after the Italian director saw her wandering around the set. She also starred in Jacques Poitrenaud’s 1962 film Strip-tease. Ford Modeling Agency then took her to New York. Her passport read, “No fixed abode.” She remained peripatetic, in every sense, for her whole life.

After Nico parted ways with the Velvet Underground in 1967, she remained within their orbit, playing solo shows at the Dom accompanied alternately by the group’s Lou Reed, John Cale and Sterling Morrison, as well as a whole slew of top-drawer Greenwich Village minstrels: Tim Buckley, Tim Hardin, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot and a 18-year-old wunderkind from Orange County named Jackson Browne. Most of this cast of characters featured on her first solo album, Chelsea Girl, which was released in October. It positions Nico at the epicentre of boho 60s pop culture, right down to its cover, a superimposition of two portraits, one from photographer Billy Name, one from filmmaker Paul Morrissey, both impeccably hip. It was a record of modish chamber-folk and one avant-disturbance: Judy Collins with frostbite, essentially. Nico dismissed it, barely tolerating Larry Fallon’s overdubbed strings but singling out his flute parts as the major irritant. Regardless of her high profile, it sold poorly, reflecting the maxim that would plague her throughout her record-making life: famous, but not popular.

Then Nico went into the desert with Jim Morrison and underwent a dramatic transformation. The Doors were riding high in the charts with ‘Light My Fire’ and Morrison was the dark prince of the burgeoning counterculture, the man Nico described as her “soul brother” (both had fathers with military backgrounds). Elektra publicist and VU cohort Danny Fields may have co-ordinated an initial meeting between the pair, and it is likely that the Lizard King was in attendance during the Velvets’ LA gigs at the Trip. There are tales of bizarre lovemaking rituals and shared blood at the Castle, a faux-medieval location and hangout for the 60s elite run by James Dean’s best friend, Jack Simmons.

While in the desert, Morrison and Nico took copious amounts of peyote, and Morrison encouraged Nico to pen her own compositions. He told her he had, like William Blake, began himself by recalling his dreams. The works of romantic poets were ingested by the duo: Shelley, Wordsworth and the suitably opiated Coleridge. Wordsworth’s recollection of Roubiliac’s Lucretius-inscribed sculpture of Newton in The Prelude, with “his prism and silent face”, was the source of The Marble Index‘s title. To Danny Fields it was a name “sufficiently gothic, lovely and meaningless”. But the rich cultural heritage it economically refers to, stretching across hundreds of years, perfectly embodies “the real Nico”’s oceanic immersion in her art: gesamtkunstwerk.

Back in New York, the fledgling composer needed an instrument. The harmonium, a pedal-powered reed keyboard of European origin but often associated with India, then a voguish destination thanks to the Beatles, was chosen. Its pneumatic wheeze sounded like “the wind” and was the same accompaniment the poet Allen Ginsberg used. Ornette Coleman showed Nico how to master it at her 51st-and-Columbus apartment. Leonard Cohen, a fan who claimed Chelsea Girl exerted an influence on his own work, was a visitor too. She would carry the organ with her everywhere for the remainder of her life (she would refer to it as her “soul”). Once a substantial backlog of songs was amassed, Fields brought her to the attention of Elektra boss Jac Holzman.

The Elektra label was in an enviable position, profiting from the Doors’ chart- topping antics but also a haven for the leftfield – the label’s first record was a recital of Rilke, E.E. Cummings and anonymous Japanese poets set to music. Holzman had exquisite taste and was that rare breed, a record company boss who did not see sales as the sole benchmark for success. He wasn’t a Chelsea Girl fan but Nico’s new songs intrigued him, reminding him of the label’s Jean Ritchie, who played the dulcimer.

Holzman praised her contralto and vibrato, and suggested that there was more colour to her vocals than the monotonous baritone she’s still renowned for. A record with a modest budget was mooted, to be recorded back west at the label’s La Cienaga studios. John Cale, now himself an ex-Velvet and fellow European-in-the-States, was enlisted as arranger and one-man orchestra, but production duties would be at least nominally handled by Frazier Mohawk, alumnus of Happy Valley School (opened by Aldous Huxley, among others) and producer of records by the Holy Modal Rounders and Kaleidoscope. The lunatics were not completely running the asylum just yet.

The Marble Index was assembled over four days in September 1968. These were sessions of flared tempers and Nico’s tears, both of sorrow and finally joy at the final playback. Even by the standards of the late 60s her new music was startling. Psychedelia and the growing sophistication of rock’s vocabulary had forged new routes, informed by both older and non-western musical modes. The

Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released in June 1967, obviously typified this brave new world of invention and optimism. The Doors were also altering rock’s spine with their Willie-Dixon-meets-Weill-and-Brecht blues/German-cabaret alloy. Nico wrenched rock from its 12-bar origins altogether, owing more, as Cale said, to European classical music. 1968 has been referred to by Richard Henderson as “the year of consequences”, a period in which the sanguine manifesto of an emerging generation was torn up amid internecine warfare and a wider culture clash. Kennedy and King were assassinated, the Democratic convention in Chicago descended into violence, American troops invaded My Lai. The streets of Paris and other cities raged with student protest.

From the deceptively jazzy chords which open ‘Prelude’ to ‘Evening Of Light”s gothic folk cacophony, The Marble Index compresses the outer limits of late 60s rock into a clipped 30-minute statement. Mohawk and engineer John Haeny devised the running order; only 15 minutes per side. They thought that was all people could take of this arcane, challenging music – Mohawk said it was not “a record you listen to. It’s a hole you fall into.” Around Nico’s harmonium and vocal, Cale drooped improvised, tumescent textures: glockenspiel, bells, bass, electric viola, strings and a nautical instrument, the bosun’s pipe. It gives the record a peculiar tension between lysergic shifts and junk stasis (heroin was definitely present, according to Mohawk), between drone and propulsion. A kaleidoscope of space-rock vibrations and percussive clatter revolves around Nico and her whirring harmonium on ‘Lawns Of Dawns’.

Elements so often used in the rock genre as simple shorthand for beauty strike discordant notes. Cale’s sonic mise-en-scène, with its bells and chimes, should be music-box mellifluous, but each constituent motif hangs independently of each another, creating unease. In his own words, “the whole is in the parts,” apparently a nod to Debussy. Free from the Velvets’ constraints, Cale’s conservatoire background is unleashed. This is evident on the disjunctive string parts on ‘No One Is There’, an astringent madrigal to the void. Nico dedicated it alternately to Nixon and Reagan, cryptic truth to power.

‘Ari’s Song’ should have been a gossamer lullaby to her son (she apparently pinned photos of him to the studio wall during its recording) but it’s an old curio shop lost at sea, careening & churning. A line like “now you see that only dreams can send you where you want to be” may seem rote whimsy, but sees contentment only in unreality. Given her subsequent introduction of Ari to drugs, the exhortation to “sail away” is more like a forewarning than a sweet sentiment over the cradle, as disquieting as Richard Thompson’s ‘The End Of The Rainbow’. As Cale’s clutter drops out of the mix, Nico hovers in unfettered solitude. ‘Julius Caesar (Memento Hodié)’ carries grim warnings from the ancients, both from the saga of the slain Roman general and the forbidden fruit of Eden, to 1968. The spartan accompaniment, just viola and harmonium, the latter’s audible pedal marking the cycles of time, houses a lyric of considerable poetic power. Its grave assessment of the illusory nature of materialism’s sunken treasures could have come from the same pen of one of the great romantic poets she was reading:

“Beneath the heaving sea/Where statues and pillars and stone altars rest for all these/Aching bones to guide us far from energy.”

The record represents an accelerated upward learning curve for an artist that went from cherry-picking other writers’ songs to composing her own in the space of an album. That same year’s Song Cycle by Van Dyke Parks was an American analogue to Nico’s European model, a post-psych, compressed compendium of American musical history, full of non-rock. The Marble Index, in the words of Richards Williams, “sprang from some ancient central European folk memory”. Both are works of inscrutable brevity. The Marble Index‘s most outré moment, ‘Facing The Wind’, with its deranged prepared piano, even sounds like a bone-rattling approximation of Parks’ own popular-music-that- wasn’t-so-popular. The sound of the other 60s.

‘Frozen Warnings’ and ‘Evening Of Light’ are the most astounding pieces of music Nico ever committed to tape; porous invention seeps from their monolithic structures. Both are masterpieces of movement and mantra, the Nico and Cale signature. On ‘Frozen Warnings’ Cale’s viola provides the drone as Nico repeats a canticle to a “friar hermit” and an iridescent organ flickers wildly, its “numberless reflections” somehow paving the way for The Who’s ‘Baba O’Riley’, Eno and Tangerine Dream. This is proto-ambient or electronic music without a single synthesiser. In 1977 Cale noted how “The Marble Index was an artefact, not a commodity. You can’t sell suicide.” True, but moods fold in on one another, creating an emotional complexity that seems too reductive to reduce to misery. ‘Evening Of Light’ is equally expansive, with harpsichords and “mandolins… ringing”. “Midnight winds are landing at the edge of time,” she sings in another hymn to the unending end of time, possibly stemming from the period in the desert she shared with Morrison. It builds to an apocalypse of scraping viola, an ever-growing abyss of bass, a sound predictive of prog’s Wagnerian proportions, perhaps even the caverns of club-land and certainly the sunburnt howl of Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Gold Dust Woman’… but mostly it sounds like the end of the world.

This was the season of witchy folk. From Mr. Fox’s ‘Mendle’ to Krzysztof Komeda’s Rosemary’s Baby soundtrack, pagan menace was yet another symptom of the darkening hippy dream (Altamont and Manson in ’69 were just around the corner). It also reflected the dark powers ascribed to the bigger-than-Jesus Magus-like rock star (see the Jagger of ‘Paint It Black’, ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ and Performance). The film to accompany ‘Evening Of Light,’ filmed by François De Menil (replete with Iggy Pop and burning crucifixes) has been described as “The Wicker Man on heroin”. In ‘Lawns Of Dawns’, it’s daylight that’s the source of dread (“Dawn your guise has filled my nights with fear”). Horror was increasingly using daylight as a scene of threat. Aleister Crowley was about to become a an unlikely lodestar for artists as disparate as Jimmy Page, David Bowie and Graham Bond, who was so convinced he was the occultist’s son he threw himself on to the tracks of the Piccadilly Line at Finsbury Park Station in May 1974.

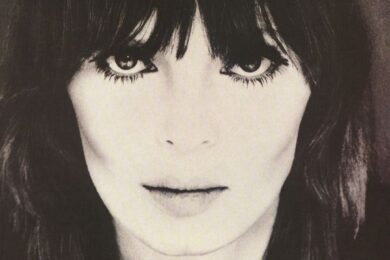

The Marble Index was unveiled at Andy Warhol’s Factory in the same month it was recorded – and shortly after Valerie Solanas’s assassination attempt on the pop artist. There were also a few Marble Index performances at Steve Paul’s the Scene to a chosen few, proof that Nico was almost a courtly cause for the arbiters of cool rather than the general public. The underground press was ecstatic but record-buyers took little notice. It was, for some, a case of too much, too soon. De facto manager Paul Morrissey loathed it (and still does). It scared “the shit out of” Lester Bangs. This had nothing to do with the blonde siren the Factory set had declared an instant icon. If this was glamour it was in the original, purest sense of the word, as used by Walter Scott in 1805: uncanny, incantatory, enchanting. Guy Webster’s black-and-white sleeve photograph of Nico in hennaed hair (allegedly to woo the redhead-loving Morrison) says it all. A skeletal, sculptural visage gazes directly at the camera exuding the fierce confidence of an artist at the peak of her powers, far from the embalmed mannequin of culture’s crude sketchpad. The Chanel trouser suits were gone too, supplanted by bohemian peasant chic, ponchos, boots, all in dark hues.

Nico never recorded another record for Elektra. This wasn’t due to The Marble Index‘s commercial failure but because, by the singer’s own admission in 1975, she was always “running away” before things happened for her. She left New York for Europe. In Rome she met filmmaker Phillippe Garrel, a director of movies featuring Jean Seberg and Catherine Deneuve who has been described as an heir to Godard and Cocteau. They moved into his father’s Paris apartment, existing on a diet of “candlelight and heroin”. She went on to collaborate extensively with him, making nine films in five years, and stills from them would grace the next two records.

Like Nico and Morrison, Garrel was an ardent chronicler of dreams. Screenplays were often cobbled together from snatches of them. Garrel’s The Inner Scar (La Cicatrice Interieure) was effectively a showcase for half of Nico’s next album, i>Desertshore (1970) and the source of its cover art. The film’s title referred, in part, to Garrel’s electroshock therapy. To the soundtrack of ‘Janitor Of Lunacy’, Nico is seen “wailing for her demon lover,” an arthouse Dido wandering through desert obscurity (locations included Death Valley, Iceland and Egypt). The stark symbolism and arid landscape are a sympathetic backdrop for Nico’s music (particularly the circle of fire and image of her on horseback that accompanies ‘All That Is My Own’). Aesthetically, The Inner Scar is very much of its time, evoking the post-60s wilderness of new Hollywood’s response to Vietnam: “inverted“ westerns, the road movie, Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout, even Hipgnosis’s sleeve designs for Pink Floyd. The new noble savage was lost and even the landscape was turning hostile.

Desertshore was made just after the death of the singer’s mother, who spent her last years in a mental hospital. Recording commenced in New York but swiftly moved to London’s Sound Techniques, co-producer Joe Boyd’s favoured studio. Boyd, with his connection to Mo Ostin, secured the singer a deal on Warners’ Reprise imprint, another visionary major label at which the nomadic Nico would find a fleeting home. Cale was on board again too, working with Boyd on both Nico and elsewhere, on Nick Drake’s Bryter Layter and Incredible String Band member Mike Heron’s first solo album.

Desertshore is airy where The Marble Index was dense and hermetic. A relic of a bygone age when a recording facility helped shape the music, it is a masterpiece of acoustics, fully utilising Sound Techniques’ multi-levelled ceiling. This was Brit-folk central, the place where everyone from Nick Drake to Richard and Linda Thompson made records full of natural reverb. Desertshore is no exception, placing Nico’s almost hieratic compositions in suitably cathedral-like dimensions. With its paeans to motherhood/childhood, it is a severe cousin to another Boyd production from the same year, Vashti Bunyan’s Just Another Diamond Day, as well as the work of forgotten female Brit troubadours Bridget St John and Shelagh McDonald.

‘My Only Child’, sung largely a cappella (with harmonies from Cale and Adam Miller) save for a few brass interjections, has a devotional purity of tone that once again chafes at the Nico caricature. The song’s choral contentment is followed by ‘Le Petit Chevalier’, a snatch of chanson sung by Ari. It’s a hangover from Marble‘s bejewelled arrangements, as is the closing ‘All That Is My Own’, with its harpsichord and brass/organ. “Meet me on the desertshore,” Nico repeats through the carnivalesque art song, a beatnik siren enjoying a moment of something approaching rapture. The transformation from demo to album version illuminates the strength of the Cale/Nico partnership, the Welshman’s rich palette again imbuing her work with varicoloured hues. The Inner Scar may share Garrel and Nico’s penchant for peering into the “gaping holes” of the human soul, but the music on Desertshore is sometimes suffused with warmth, full of chiaroscuro contrasts.

‘The Falconer’ had already appeared in another Garrel film, Le Lit De La Vierge, in a different form. A coded love-letter to Garrel, whose “silver traces” have erased her “empty pages”? A homage to Warhol, after Solanas? She sings from lofty altitudes, remote and commanding, as Cale conjures musical sturm und drang, briefly shifting to a lullaby for the “father child” and “angels of the night”. The imagery suggests allegory. These are glimpses of revolutionary light, flickering from the dungeon of oppression, informed by the times after the riots in Paris, again something that Garrel’s work addressed.

Traces of politics may obliquely permeate her music, as does religious intensity, but eventually The End… would reveal that nihilism was to be her only true cause (the negation of both).

‘Abscheid’ and ‘Mutterlein’ are both German-language songs, stentorian lieder full of descending piano chords and scything strings. ‘Janitor Of Lunacy’ is putatively an elegy to former beau Brian Jones, who died face down in his swimming pool in 1969. His undervalued role as the Rolling Stones’ colourist, from ‘Lady Jane”s dulcimer to being an early ambassador for world music (Brian Jones Presents The Pipes Of Pan At Joujouka), paralleled Nico and Cale’s work on The Marble Index. If it is indeed about Jones, it’s hardly the fond adieu of Mick Jagger’s butterflies in Hyde Park. A song of infancy and demons, it casts Christopher Robin in dark shadows. ‘Afraid”s ivory-tinkling intimacies carry equally heavy baggage, assuaged by the pared-down prettiness of Cale’s arrangement. A throwback to Chelsea Girl‘s chamber-folk and a European sister to Joni Mitchell’s “penitent of the spirit”, ‘Afraid”s anti-romanticism looks forward instead to the soul-searching of Antony Hegarty. Beautiful and alone, the song is a cri de coeur sung to a mirror image but seems deeply poignant rather than narcissistic.

There was a performance with Cale and Incredible String Band’s Mike Heron at Camden’s Roundhouse. The same year of Desertshore‘s release, Reed exited the Velvets. Two years later, Nico, Reed and Cale would briefly reunite at Paris’s Le Bataclan club for a relaxed performance that was as close to bonhomie as the trio got. Interviewed by Rolling Stone in 1970, Nico, still the face of the VU to many, sounded as sanguine as she ever would. She talked about the deserts that had inspired her songs, the urban ones like New York and the real ones she visited, often as a film location with Garrel. Liberated from the VU and Warhol’s crowd, she was nevertheless “unsure of what role she was playing”. She mentioned how all the people she knew were turning from “drugs to wine”. Like so many things she said, this wasn’t strictly true. There were more movies with Garrel and a lengthy gap between Desertshore and 1974’s The End… The junk was taking its toll.

The 60s was a time of radical upheaval that had spun out of control by the decade’s end. The 70s grappled with the aftershocks. Political activism often turned nasty and insurrectionary attacks were frequent. Rock music became overwhelmed with fatalities and burnouts. Most significantly for Nico, her soul brother died in Paris in July 1971. She had barely encountered him since their desert sojourn, but just prior to his death she saw him in a long black car, oblivious to her presence. Although it would be another three years until her next record, when it did arrive, The End… unified this weltschmerz. The album was both a collection of “terrorist songs” and an epitaph to the Doors frontman. Not only was the title track a cover of his band’s most infamous song, ‘You Forgot To Answer’ was a self-penned elegy that recalled her last sighting of the Lizard King. ‘You Forgot To Answer’ also became, effectively, her own swansong, as the last number she ever performed on the stage years later.

Another record, another label. The similarly itinerant and coke-addled Cale was now signed to Island and had brought Nico with him, against some resistance from Chris Blackwell’s label. Cale himself had just produced his most accessible record with the symphonic rock of Paris 1919.

On 1 June, 1974, less than a month after Graham Bond’s suicide at Finsbury Park Station, Nico played a gig at the nearby Rainbow theatre with Kevin Ayers, John Cale and Eno (augmented by Robert Wyatt on percussion and Mike Oldfield on guitar). This avant-prog/high glam summit, its reputation sealed by the subsequent live album’s Mick Rock photo of the four artists, is a fissure in which all their idiosyncratic elements – too quirky for prog, too cerebral for glitterbeat ordinaire – seep in. According to David Sheppard’s Eno biography, On Some Faraway Beach, Cale and Eno even came up with a name. Alas, Les Chevilles Exotiques (“the exotic ankles”) failed to classify this madcap musical intelligence satisfactorily, and the Rainbow collective was short-lived. Mick Rock’s photo was taken the day after Cale caught Ayers sleeping with his increasingly estranged wife Cynthia Wells, aka Miss Cynderella.

Glam rock, especially in its highbrow, art-school incarnation, was the aesthete’s response to the era’s uncertainty: the tangled web of late 20th-century culture and the lack of absolutes in post-modern society. By 1974 its own gaudy garments were coming apart at the seams. Bowie’s Diamond Dogs was a collection of fragments of an abortive 1984 musical and a dystopian final bow for Ziggy Stardust. Other works of Grand Guignol glitz included Sparks’ Kimono My House, T. Rex’s ‘Teenage Dream’ and the post-Eno Roxy Music’s Country Life. Nico’s former bandmate Lou Reed had enjoyed a commercial breakthrough with his own Bowie-assisted take on glam, 1972’s Transformer. His 1973 album Berlin, however, was a dramatic volte-face, a buzzkill masterclass to rival Nico’s work. While obviously not glam rock, decadence, that amalgam of decay and elegance, is all over The End… Haunted and haunting, it’s the sound of attrition.

Recorded once again at Sound Techniques and engineered by John Wood, The End… sees the osmosis of Boyd’s warmth dispensed with altogether. This is a turf war between Nico’s atavistic dirges and the futurism of Eno’s VCS3 manipulations, most potently captured on ‘Innocent and Vain’. If its predecessor had been light and shade, the darkness was encroaching on The End… You can almost hear the black spaces – it’s aural Caravaggio/German expressionism. A still from a Garrel film, Les Hautes Solitudes, adorns the sleeve. The record is full of lugubrious piano and Eno’s synths, by turns air-raid white noise and spectral ambience, a kind of post-blitzkreig Weimar cabaret. “The high tide is taking everything,” she sings through the wind, her wavering vocal duplicating its gusts.

Cale supplied the usual chimes and bells, although he claims Nico handled the arrangements herself. The life-sapping effects of heroin are smeared across the record, but it also, perversely enough, represents a seizing of the reins. Her occasional Arabic phrasing hints at what would come on Drama Of Exile (1981). ‘It Has Not Taken Long’, with its empyrean choirs and Floyd-like pulse, offsets a particularly sinister vocal. Another constellation shimmering in the blackest night sky, ‘Secret Side’ juxtaposes swirling synth fanfares with disturbing images of “unwed virgins… tied up on the sand”. The song was debuted much earlier, and has been taken as evidence that Nico was raped, allegedly by an American GI in Berlin who was subsequently executed after the teenage Nico testified against him. If true, then this trauma perilously linked sex and death for her at an early age, perhaps explaining the sensual deprivation of so much of her work. Nico might have been a reader of the romantics but her execution frequently uses the barren chill of the modernists.

The End…‘s edges effervesce with the iconoclastic spirit of early Roxy, as much as Morrison’s spectre looms large. There’s also the black-hole horror of the most infernal moments from Roxy’s For Your Pleasure. On songs like ‘You Forgot To Answer’, there’s a whiff of Pleasure’s bleak, valedictory ballads ‘Sea Breezes’ and ‘Strictly Confidential’, but divested of their Noël Coward camp. ‘We’ve Got The Gold’, inspired by Andreas Baader, even sounds like a twisted sister to Pleasure’s ‘The Bogus Man’, full of the same spy-movie menace but stripped of the Can-like rhythm. The song is one of Nico’s rocks to be “thrown at the world”.

The End… is perhaps weighed down by the baggage of its last two songs, the title track and ‘Das Lied Der Deutschen’, the German national anthem since 1922 (and featuring passages outlawed in 1945). Morrison talked about ‘The End’ as a “blank canvas”, and Nico’s reading is a fulfilment of the song’s oracular promise. She reduces it to spectral sprechgesang against a backdrop of rudimentary piano chords, frayed acoustic guitar and organ stabs. The oedipal section climaxes with a vampire’s howl into the oblivion of nothingness. The oppositional flashes of beauty that coloured her previous work had been extinguished, replaced with Stygian dread. For all its brilliance, ‘The End’ fits more neatly into the doomed valkyrie of popular image than The Marble Index and Desertshore. Even the song’s incongruous rattlesnake-shake ending cannot satisfactorily resuscitate her. “C’mon baby, take a chance with us,” she lifelessly croons as Phil Manzanera’s guitar unleashes a few squalls. The listener would have to be insane to comply.

She claimed the German national anthem cover was a piece of left-wing iconoclasm, similar to Hendrix’s inflamed debunking of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’. Audiences exposed to her rendition in Berlin hardly took it that way. The major-key Haydn melody was anomalous enough closing the album. Live, it provoked a near riot from the predominantly left-wing audience, suggesting again that Nico was a purveyor of warped political ideas. The irony is that she had scant regard for Germany, and was reminded of why she left every time she paid the country a visit. Some claim she was schizophrenic. It almost seems folly to impose a moral framework upon her beliefs, deranged and as inconsistent as they were, particularly as she became more dependent on drugs. Even accounts of those close to her are maddeningly conflicting. Danny Fields, for instance, has been quoted as claiming she was both “a Nazi and as far from being a Nazi as you could possibly be”. She was, according to many, capable of being a brat.

1974 was also the year she played Reims Cathedral with Tangerine Dream, in another riotous performance that elicited a ban from the Vatican on all subsequent rock shows within its sacred buildings. The progressive synth wizards she played alongside were avatars of a new Germany, the post-war tabula rasa of kosmische. A forward-thinking, communal hippy spirit was one aspect of many of these bands. The cosmic jams of Amon Düül rejected Anglo- American rock, like much of Nico’s work, but the band also shunned the terrorism of the Baader-Meinhof group. Conversely, Nico was vocal in her support, claiming that nihilism was the only true religion. Elsewhere, Can mirrored the monotony versus variety of The Marble Index.

One can only wonder what music would have been made had Nico aligned herself more closely with these forces. ‘Das Lied Der Deutschen’ suggests that such incisive thinking was no longer in her grasp. From the Stooges to Lemmy, from Roxy’s uniforms to Siouxsie Sioux’s armband, the use of Nazi iconography in rock is hardly uncommon. This unpleasant flirtation would become rife once punk flicked the Vs at the past generation, largely through the puerile antics of enfants terribles rather than the harbouring of any malevolent support for the ideology. Nico’s suspect dabblings meant that she was rarely afforded the praise she sought and frequently deserved.

Garrel claims that Nico’s only true love was art, and that this was ultimately what destroyed her. He mentions the “destructive mirage of art” that brings an artist closer to death. As much as the music Nico made from 1968 to 1974 freed her from the burden of the model beauty she hated, the drugs she took to slow down her thoughts proved to be, as is so often the case, a short-term catalyst with long-term consequences.

Addiction eventually slowed down more than Nico’s thoughts. For the rest of the 70s she was musically inactive, with only the odd live appearance interrupting her silence (there are rumours that she thought the Black Panthers had a contract out on her). In this absence, her music cast its shadows. The second sides of Bowie’s Low and "Heroes" seem reminiscent of her own desolate, Eno-assisted topography on The End… From Joy Division’s Closer to Magazine’s ‘Permafrost’, post punk’s rejection of warmth, romance and blues- based music owes something to her. She’s there in the sangfroid of everyone from Grace Jones to Siouxsie Sioux (particularly the desert noir of Siouxsie And The Banshees’ Juju, which is turbocharged with pop hooks and tribal drums). Dave Stewart recalls an early meeting with Annie Lennox where the then Aberdeen waitress played sad songs on a harmonium in her flat, a kindred spirit perhaps, before the 80s lacquer was applied.

Nico re-emerged in that decade just as goth took shape, when the Velvets influence was paramount for everyone from the Dream Syndicate to the early Smiths. Vestiges of inspiration remain on Drama Of Exile (1981) and Camera Obscura (1985), chiefly on the second version of the former, in which a rhythm section and ethno-instrumentation refutes both the idea that the well had run dry and that she was an Aryan extremist. But by now Nico was a habitual addict, living in Manchester and buoyed by a nebbish bunch rather than the various visionaries she fed off in her prime (Cale remained one of the few constants in her life). This is the anti-glamour of Young’s memoir of poor hygiene, smuggled drugs, cheap motels and the moral-compass departure of a mother-son heroin habit. Renowned for its myth-busting hilarity, his book is, at times, unbearably sad, especially when she’s confronted with remnants of an era she was celebrated in and moribund without.

Throughout her life, Nico sought the company of those who were already gone; all her homes were foreign countries, all her lovers were ghosts. Similarly, Nico’s best work exists in an odd midpoint between anti-romance and romance, cobwebbed caverns and smack dens, the imperious and the fragile. As with Tennessee Williams’ verdict of Blanche DuBois, Nico was the “strongest weak person”. Ohne festen wohnsitz (“without a permanent residence”).

Nico died in July 1988 from a haemorrhage after falling off a bike in Ibiza (Garrel’s 1991 film J’Entends Plus La Guitare dramatises the event). She was, it seems, on the mend, on methadone and working with Marc Almond. If this was purely about personal biography, the story would be a tragic one. It isn’t. Although she felt kinship with the 50s beat-era, Nico believed her time was yet to come. Considering the genuinely progressive and psychedelic, neo-classical nature of particularly the first instalment of The Marble Index trilogy, she surely had a point. The critical stock of those three works continues to grow, and echoes of Nico are heard in artists as disparate as Broadcast, Tracey Thorn, Elliott Smith, Suede and Opeth. Bjork covered ‘Le Petit Chevalier’; Bat For Lashes walked onstage to it.

2007’s The Frozen Borderline – 1968–1970 collated the sessions from The Marble Index and Desertshore, offering extras on each disc that underlined the strength of the Nico/Cale partnership. Last year saw The End… get the deluxe treatment too, in an example of worthwhile re-mastering, accompanied by live versions of the title track that arguably surpass the original. Recently X-TG’s (aka Throbbing Gristle) Desertshore/The Final Report album revisited tracks from the 1970 album with performances from Antony Hegarty and Marc Almond, proof that Nico is as talismanic as ever to “outsider” artists, those who exist beyond the parameters of conventional rock classicism and the Beatles, Stones and Dylan canon. While Reed was welcomed into the pantheon a long time ago, Nico and her former foil Cale remain true avatars of the VU spirit, existing on the margins. As the forced fun of pop’s jukebox and the blare of recycled retromania obliterates the “weird”, the brutal uncompromising majesty of this trio of albums, a magical misery tour, remains more relevant than ever.