Just who is Iain Sinclair? Is he the literary magus who for over four decades has published frenzied works of poetry and prose that have tangled and untangled the entrails of east London and the Thames Estuary myth? Or is he the politely grumpy talking head, whose reputation as chief subversive of London letters has, in recent years, been boiled down to an enfeebled, televised harrumph?

The frustrating thing about Sinclair becoming the BBC-friendly go-to guy for a nay-saying soundbite about the 2012 Olympic project is that, along the way, the poetry became lost in translation. Unlike the made-for-TV sniping of that other Auntie’s Anti, Will Self, the ideas contained in Sinclair’s prose have never seemed a good fit for Newsnight. Sinclair becoming a Beeb regular is indeed a mark of his success: how his East End ramblings (first physical, then verbal) were understood by those interested in the margins of the city. Yet his role on the lit-hungry Londoner’s coffee table has led some to question whether there was ever anything particularly subversive about Sinclair’s prose. One or two younger, angrier documenters of London have suggested that he is a kind of Pied Piper of east London gentrification, leading arts workers and wannabe deep topographers on a merry dance up the property ladder. The oldest story in the estate agents’ manual is that new territory must have a misspent past to define it, and Sinclair dug it up for curious clients to digest in a series of heavy tomes.

A great strength of this vinyl-only release (the first from new label Test Centre) is how it relieves Sinclair of this particular entrapment – via a whole new one. He’s physically contained as a dismembered voice emanating from a vinyl record, and contained by history, as the readings here come from the 1970s prose poetry of Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge, and the 1980s and 90s fictions of White Chappell Scarlet Tracings and Downriver.

What it projects is the feverish excitement of Sinclair’s pre-Millennium explorations. How he got people obsessed with the mysterious, history-bound names he recited during his whistle-stop flow – "Sinclair texts were like internet sites before the fact," wrote Ian Penman in 2005, "full of links for the interested reader to follow" – and the shapes in the map that Hawksmoor churches made. There is a point on track one, side A, when post-punk era Sinclair (taken from 1979 recording The Lud Tapes) and 21st Century Sinclair (recorded for the vinyl at St Anne’s in Limehouse in November last year) collide. The earlier Sinclair starts to zoom ahead, before the two converge. The younger sounds somehow older than today’s model – wiry and weedy like a Dickens character, a wizened old gent telling a tale by the fire, eyes alight. The 2011 recording of a deeper, more stable voice overtakes: "We stumble into the realisation of a doppelganger principle, and the feeling was already present of a secondary personality developing… Not quite myself today."

His voice has been covered in echo and delay. White noise and incidental sounds resulting from field recordings: ferocious winds by the Thames; the rumbling groan of London traffic; a sinister, mechanical click and clack that threatens to overwhelm. Although the texts read here are all 20 to 40 years old, it doesn’t feel like a nostalgic pursuit. Test Centre, which seems like a Sinclair fan club as much as a record label, are releasing a second record, out in March, by Chris Petit, the master solemnist behind Radio On and the modern classic Content, and friend of Sinclair, who regularly appears in his prose. Some of the raw materials on Chris’ LP were made with Sinclair and vice versa. Test Centre also publishes a magazine (the latest features Steve Moore and Lee Rourke along with Sinclair) which pays lip service to Sinclair’s own publishing when he ran Albion Press in the 70s. It seems an attempt to rehabilitate Sinclair – and in turn, rekindling the kind of subversive tracks in the landscape etched out by he and his post-60s peers.

This record is the inverse of the posturing Swandown, a pseudo-prankster escapade caught on camera and released as a film this year that involved Sinclair and arch-collaborator the filmmaker Andrew Kötting (there is a sample from it, on side B of this record). Travelling from Hastings to east London, the epicentre of the Olympic Games, in a swan-shaped pedalo, Sinclair and Kötting set out to plot a course into the heart of corporate regeneration and register an absurdist V-sign to the Grand Project (a similar tactic to that which London Orbital did so well in 2001). Yet it felt like a non-event, characterised by awkward exchanges with people on riverbanks and hammy references to Ophelia. Tight-lipped for much of the film, Sinclair seemed to exert the doomed serenity of Tenbrucke in Downriver during the passage that describes his suicide, which is recited here.

"They had abandoned him, his familiar desires. There was no fret left in them… He opened his mouth and swallowed everything that was coming." As if mindful of his fate should he complete the mission, Sinclair aborts it before reaching the Olympic site to head for City Airport to attend a literary engagement in the US, leaving Kötting to carry on alone.

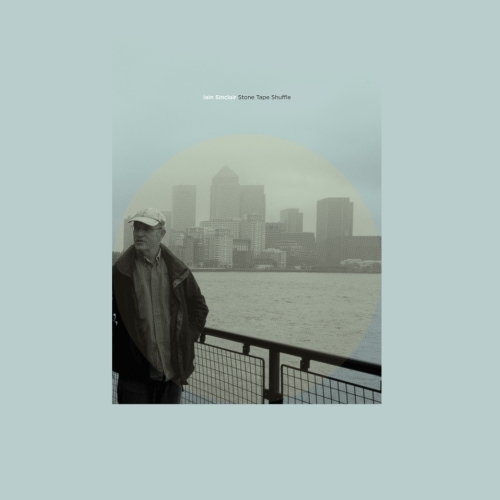

Sinclair appears in a baseball cap on the front of this record: a genteel literary version of a grime MC in front of his enemy’s crib, the Canary Wharf development on the other side of the Thames. When the Olympic bid was given the green light back in 2005, his rap finally found its place in the cultural mainstream. But poetry doesn’t take sides so easily. It feverishly records and regurgitates in distorted shapes, and in the best instances offers up new forms, as Sinclair reminds us on this record.