Two weeks before Palestine defeats Israel and US opposition by receiving an upgrade to UN member state observer status, we’re speaking to Joe Sacco over the phone from his home town of Portland, Oregon. It’s during Israel’s Operation Pillar Of Defence and a day after the air attack which kills Hamas military leader in Gaza, Ahmed Jabari. Israel’s Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu is sabre-rattling over the threat of an Israeli ground attack following retaliatory rocket fire from Gaza.

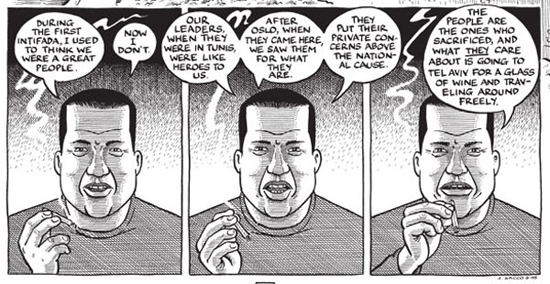

“I grew up thinking all Palestinians were terrorists,” says Sacco of his US high school and college education. “That wasn’t from studying the issue closely, that was from just absorbing what I read in newspapers. Newspapers were reporting a lot of facts,” he says, enunciating for effect in the absence of being able to make hand quotes. “You can report objective facts – the hijacking of an airplane, attacks on a bus, killing hostages – but often what objective facts don’t provide is a context of other crimes.”

The falsehood of objective journalism in the UK has already been exposed by the Leveson Inquiry. Public campaigns for justice such as Hillsborough and now Orgreave are correcting distorted history by demanding justice for the falsely accused, their supposed crimes or misdemeanours reported by a complicit late 20th century British press. Despite its cretinous sensationalist tabloids, UK media is traditionally respected through the US and Europe. So it’s troubling to consider which version of the truth that the press of other western democracies has been peddling for the past 50 years.

“You can report objective facts selectively and without context and give someone an impression,” continues Sacco, “as I was given by so-called objective journalism: that Palestinians are pure and simple terrorists. It took self-education. I was never going to come up with another viewpoint by reading the American press.”

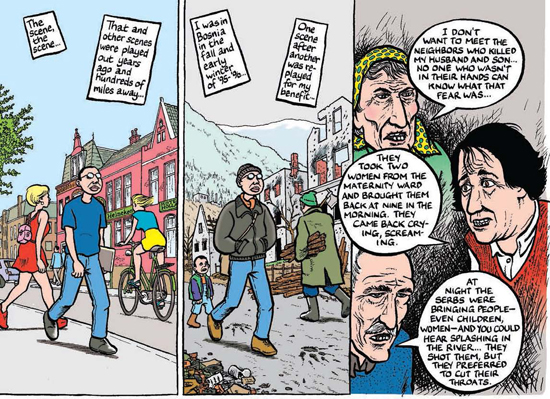

Sacco is an authority on the Israel-Palestine conflict. He spent two months in Gaza and the West Bank in the early 90s as research for the award-winning Palestine, a graphic novel both educational and entertaining in equal measure. Following the award-winning Safe Area Gorazde, concerning the Bosnian War of the mid-90s, his masterwork, the harrowing but essential historical analysis, Footnotes In Gaza, Sacco has spent his career defending the inevitable subjectivity of his work.

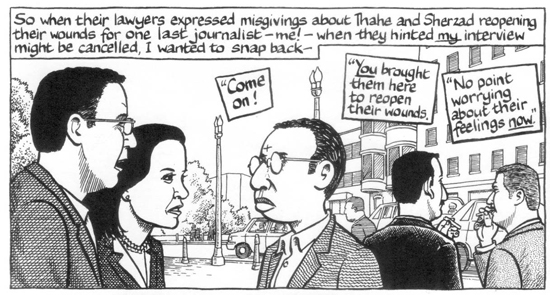

Unlike press or TV news, Sacco is part of his stories. He deliberately makes his stories subjective by appearing in them and documenting the influence or cause that his presence – or even impact – might have on the story. But to Sacco, this is not far removed from traditional ‘embedded’ journalists reporting from war zones. “The journalist is always ‘in the shot’ in real life,” he argues. “People are always responding to a very specific individual. Obviously there’s a lot more going on that you’re getting [from mainstream news sources]. At the very least I want to let the reader in on that.

“The problem with modern journalists is that they truly believe they are objective. They believe that they’re in the service of some platonic idealism of journalism. I would rather try to be as honest as possible and source information as accurately as possible but admit that by meeting and befriending people, they respond to you. I want all of that to go into my story; I want to be upfront about it."

The dissenters state that involving oneself compromises the balance of news reportage; if you present yourself as befriending interviewees, whether they are insurgents, victims or war-mongerers, surely the bias is compromised to such a point that reportage simply becomes a diary or travelogue – or even worse, thinly-veiled propaganda. “I don’t agree with that,” states Sacco plainly. “What objectivity has come to mean as far as its journalistic definition is that there are two sides to a story, you just present both sides of the story then let the reader decide. There’s never just two sides. To me, a journalist is someone who you have to put a bit of faith in. If you know what a journalist’s world view is – by this point most people who know my work will have an appreciation of my world view – then you understand the filter that you are reading the thing through. You’re reading it through a very individual filter and you can judge better.”

As for Sacco’s own worldview, even his harshest critic couldn’t deny its formation was through a well-informed upbringing. By the age of 11 he had already lived on three separate continents. Born 1960 in Malta to a father who was an engineer and his mother a teacher, the Sacco family joined the last wave of post-war European emigration shortly before Malta gained independence from Britain in 1964. At the time, Australia was paying passage to receive European immigrants. But following prejudice in their Australian workplaces, Sacco’s family made the decision to move to Los Angeles when Joe was 11.

Although he describes the Australian school system as “top notch”, the young Sacco was astounded by the apparent seclusion of the USA: “when we first moved to Los Angeles, one of the first questions the American students would ask me was, ‘what language do you speak in Australia?’ It flabbergasted me. Because in Australia we learned a lot about other people’s languages and societies – there was a real emphasis on that – whereas the Americans were very insular. They didn’t even know we spoke English!”

Travelling the globe at such an early age gave Sacco a head start with his cosmopolitan way of thinking. Although never a victim of bullying like many kids new to a school or area, his childhood relocations would inform his global view and eventually his work: “You make some friends but there’s a certain alienation. You realise you’re different – suddenly you’re in a new place with problems you’re unfamiliar with. Moving around a lot, there is a certain rootlessness to it – but in the best possible way. I don’t like the term ‘globalisation’; it’s used in a positive context, but I see a lot of negatives with it. But I had the best of what globalisation is: having moved around, not being too rooted.”

The results of such rootlessness would be demonstrated in Sacco’s studious childhood. While his friends would be out playing in the open air, he’d be indoors reading vintage comics like The Phantom or Mad. From the age of six he took his first formative career steps by drawing comics that were inspired by Bob Hope movies set in exotic locations. His more recent artwork is influenced by Will Elder and the surreal autobiographical characteristic of Robert Crumb – similar to Sacco’s own style of self-deprecatory self-portraiture. His two fields of expertise married together when he started journalism classes at high school.

“It was like a light went off in my head,” recalls Sacco. “I used to interview foreign exchange students and I realised I loved hearing people’s stories.” Combining his love of comics and drawing with his talent for journalism would consolidate the way in which Sacco viewed and interpreted the world, and his natural integrity: “I wanted to be honest at what a journalist does and the trouble of getting a story. It gives [the reader] an insight to the places and how journalism works – or doesn’t work.”

In the preface to his new collection of graphic conflict zone reportage – simply but appropriately titled Journalism – Sacco admits that using comics as a medium forced him to make that unconventional decision of subjectivity over objectivity. “The very fact of drawing makes you participate,” says Sacco. “Beyond that, you make choices when you draw. Drawing is about choices: how am I going to draw 15 people being shot down in cold blood? Am I going to draw it cynically? Am I going to draw their faces? Whatever you decide, it’s a choice. So just by definition, drawing is subjective.”

But is the subjectivity of his comic art so different to other media? The same could be said for photojournalism; especially the way a scene is shot, lit and the way the resultant photo is cropped, captioned and so on. Sacco cites Kevin Carter’s 1993 Pulitzer Prize-winning picture of the Sudanese famine. A Sudanese child is bent over double on the ground, appearing to be dying of exhaustion caused by malnutrition, with the sinister spectre of a vulture in wait just behind her. When published in The New York Times it caused an enormous outcry; readers flooded the paper with enquiries of the girl’s fate. It was then subsequently alleged the picture was taken at a UN feeding station; the girl was momentarily left alone while her parents fetched corn and the vulture was much further away than the photo’s perspective suggests. “It might not have even been the photographer,” suggests Sacco. “He is obviously thinking in terms of impact and everything, but if you looked at his whole roll of film, most of the pictures might have shown otherwise. An editor could have made that choice because it was striking.”

It would be easy and create less work for Sacco to conflate people or scenes for the sake of narrative and to limit over-writing in his chosen form of media, but this he says is a definite no-go area. Although he’s never been accused of being misleading, he has been questioned concerning the way some scenes are represented. As some of his artwork panels will picture a historical scene related by an interviewee, ultimately there’ll be an element of creativity involved. For example, he pictured a child being harassed by Israeli soldiers from above, giving the reader the feeling of oppression from the child’s point of view. To which some people objected. “It’s a very subjective choice but when I’m drawing something like that I’m thinking about the child – I’m not thinking about the poor soldiers being neutral. The child is being harassed by soldiers: it’s wrong. You’d think it was wrong if you saw it on the street.

“Despite what I’ve said about being subjective, you realise these are very powerful tools and you’re careful about how you use it. I could make things look a lot worse too, but I think about how I’m going to present it. You don’t want things to look spectacular, you don’t want violence to somehow look beautiful. There are a lot of ways to think about what’s in your hands. There is an inherent danger with subjectivity: there’s a great responsibility with something on which you have a view and how you are going to present it.”

Sacco is on good terms with his war correspondent peers in the mainstream media. He admits most of them have been in far more dangerous war zones than him – mostly because of their necessity to be constantly on the move in search of hard news and the latest updates of a conflict. But they, in turn, also covet his ability to remain in one area for a period of time to uncover a back-story: the causes, the history of a conflict and its lasting impact on the civilian victims. Recent budget cuts have hamstrung TV news companies to produce such documentary style features, but it’s where Sacco’s stories flourish. And considering his alternative means of story gathering, those other correspondents appreciate his work. “Most of them like what l’m doing because it’s true to their own experiences,” he says. “A lot of reporters don’t have the freedom to report in the same way. They see what I see but what’s required for them isn’t the small stories that build up.”

Illustrating conflict is nothing new: before TV, or even photography, troops would go into battle with a painter attached to their regiment. The idea was to document the life of a soldier, but ultimately they would be propagandist. It’s something Sacco has found out for himself during research for his current project, a book about World War I, produced as a single illustration in the style of a concertinaed fold-out book (“let’s just say it’s like the Bayeux Tapestry – that’s my model!”).

“If you look at the World War I photographs in London’s Imperial War Museum, in 99 per cent of cases, it’s the German dead,” he says. “The pictures by themselves are grotesque but it’s no worse than what you might see on a battlefield. They wanted to show what being a soldier was like, but of course they didn’t want to harm the war effort. So that’s already a subjective decision.”

Such research and Sacco’s work itself is undoubtedly wearing, the daily trauma of picturing killing and genocide – even if it is illustrations. Producing Footnotes In Gaza particularly was itself an exercise in trauma and depression. “As hard as those stories were to hear in person, it was easier to hear those stories than it was to draw those stories,” he says darkly. “Because when you’re hearing the stories and you’re trained as a journalist, you’re trying to corral the person telling the story to stay on track. Usually there are 13 other stories around them and it takes so much concentration to get the story that you’re behaving almost coldly. It’s like you’re a doctor extracting an organ. All you’re interested in is removing that organ and sewing up the patient with as little harm done as possible. You’re very clinical about it; almost like a technician. There’s a coldness. It’s kind of a good thing because you’re distanced.

“When you’re drawing it’s hard to be distanced. In fact you have to inhabit what you’re drawing – the person you’re shooting and the person falling to the ground. You have to feel how their hands would be placed and so on. You find yourself almost doing this reflexively with your own body, to find out how you would draw those muscles. Is it depressing? If you see enough of the world it’s depressing. Drawing it is like taking a concentrated dose of it.”

It’s something that’s affected Sacco so much that he’s moving away from conflict zone reportage – for the time being at least. After completing his World War I book, during 2013 he’ll be working on an entirely different project. “It’s a mixture of fiction, journalism, essays and all sorts of things with a number of different subjects,” he says enthusiastically. “The first one will be ancient Mesopotamia. I’m really changing gears now – probably because I’m burned out.”

In the meantime, Footnotes In Gaza is being adapted into a full-length animated feature film. Currently in pre-development by French company Tu Vas Voir, the screenplay is being written by Gill Dennis and the film directed by Denis Villneuve. It follows in the footsteps of Marjane Satrapi’s hugely successful graphic novel Persepolis and subsequent movie – although unlike Statrapi, Sacco isn’t directly involved with the animation, preferring someone else to take the strain. “I’d rather see someone else’s impression of it than redoing my work in another form. I don’t have the energy or emotional ability to do it.”

From graphic novel to film, the stories of Sacco’s Israel-Palestine conflict victims disaffected by generations of war are finally going down in history in their own words. Subjective, maybe, but not necessarily any less reliable than any other modern-day news source. “People know I’m sympathetic to the Palestinian people,” says Sacco. “So you can dismiss it as ‘he’s always an apologist for this, that, or the other’. But often the Palestinians are saying things that are awful and things are happening that aren’t going to make them look good – but you have to report it honestly.

“I definitely believe you should present another side, but as someone who you want the reader to trust, I have enough faith in myself as someone who is discerning to say, ‘yes, I’m presenting this side of the story, but I was there; I saw what was happening and it’s bullshit – that side of the story was bullshit. If I was on the ground and met people and saw things with my own eyes, I’m not going to wash that out by feeding people the opposite just for the sake of so-called objectivity. I’m much more interested in truth. I think you can find truth even through a subjective point of view. But if you see things that don’t fit your world view you still have to report those things.”

Journalism is out now, published by Jonathan Cape

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more