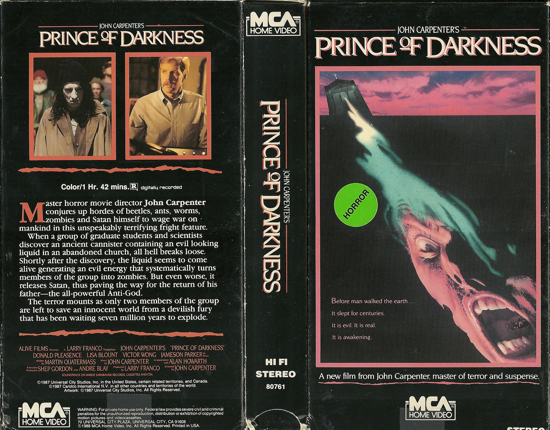

Released in 1987, Prince of Darkness is the second part of what director John Carpenter has dubbed his ‘Apocalypse Trilogy’, which begins with The Thing (1982) and ends with In the Mouth of Madness (1995). Though the three films are different stories and not directly connected, they all deal with a threat that could destroy humanity if allowed to go unchecked.

Prince of Darkness involves a covert Roman Catholic order called the Brotherhood of Sleep. This sect have been watching over a cylinder containing an ancient secret that’s been hidden in a church crypt for centuries. When the last guardian dies, Father Loomis (Donald Pleasence, whose character in 1978’s Halloween was of course also named Loomis) calls Professor Howard Birack (Victor Wong) to investigate the mysterious entity.

Birack is seen delivering a lecture that undermines what we believe to real: "Say goodbye to classical reality because our logic collapses on the subatomic level into ghosts and shadows… While order does exist in the universe, it is not at all what we had in mind." Among his diverse group of students are Brian Marsh (Jameson Parker) and Catherine Danforth (Lisa Blout), who have fallen in love. This is a seemingly trivial event in the face of the earth-shaking revelations to come, yet in typical Carpenter fashion it will prove to be the most important.

There is a palimpsest in the crypt, its parchments having had their text erased to make room for other writing, with the original entry remaining faintly visible. One of the academics, Lisa (Ann Yen), is an expert on ancient languages and begins to translate the book. She discovers that the liquid in the cylinder is in fact the Son of Satan: ‘And the Prince of Darkness was Himself sealed, that old life, called the Devil and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world.’ The tome also says that Jesus was of extraterrestrial origin and came to Earth to warn humanity. After his death the Church kept this quiet, preferring to portray evil as a metaphor rather than a corporeal presence.

The Prince of Darkness’s essence invades those in the vicinity, so that they can work as his minions. One student is murdered by a ‘Street Schizo’ (played by Alice Cooper). Another member of the group, Kelly (Susan Blanchard), is bruised. Her bruise forms into the shape of the astrologer’s staff, an occult symbol (rock fan Carpenter got the idea for using it from the sleeve of Blue Öyster Cult’s classic 1976 LP Agents of Fortune). Kelly has been chosen to be the vessel for the Anti-Christ.

Another message comes from the now-possessed Lisa. She ceases maniacally typing ‘I LIVE’ on her computer screen, and instead informs those who survive using the same medium: ‘You will not be saved by the holy ghost. You will not be saved by the god Plutonium. In fact, YOU WILL NOT BE SAVED!’ This scene is clearly inspired by The Shining, and serves to underscore Carpenter’s occult/technology theme: the Prince of Darkness is telling the survivors through Lisa that neither science nor religion can save them. The uninfected all share the same dream, beamed directly to their subconscious from the year 1999. It shows a shadowy creature appearing in the doorway of the church. A voice accompanying the vision warns them they are witnessing an event they must prevent from happening: "This is not a dream…"

Carpenter was inspired to write Prince of Darkness by his interest in quantum mechanics. He told biographer Gilles Boulenger: "I’d been doing a lot of reading on theoretical physics and atomic theory, and I found it to be amazing. Not only amazing, but also it was transforming the truth of it all. The point of quantum mechanics is something called ‘observer-created reality’, which in one bold and terrifying stroke slams at the heart of human perception and its understanding of the objective Newtonian reality. So I thought it would be interesting to create some sort of ultimate evil and combine it with the notion of matter and anti-matter. Since there is a mirror of anti-matter for every particle of matter, I thought it would be great to have an anti-God, namely a mirror opposite of God that would be totally evil. I started from that premise and worked in various ideas."

He was also heavily influenced by English screenwriter Nigel Kneale, who merged the occult and science to great effect, most famously in the venerable Quatermass and the Pit. This is reflected in Carpenter adopting the pseudonym Martin Quatermass as his writing credit. Kneale didn’t take this as a compliment and was greatly vexed. (That said, looking at interviews which Kneale gave over the years, he was pretty irritated by everything.) The pair had previously fallen out over the screenplay of Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982). Nevertheless, the influence of Kneale looms large in Carpenter’s filmography. In tribute, the promotional material for Prince of Darkness went as far as inventing the following biographical information: ‘Martin Quatermass, born in London, England, is a former physicist and brother of Bernard Quatermass, the rocket scientist who headed the British Rocket Group during the 1950s. Quatermass graduated from Kneale University with a degree in theoretical physics. Prince of Darkness is his first screenplay, and he assures that all the physical principles used in the story, including the ability of subatomic particles to travel backward in time, are true. Author of two novels, Schrödinger’s Revenge and Schwarzschild Radius, he currently lives in Frazier Park, California, with his wife, Janet.’

Among the many parallels between Quatermass and the Pit and Prince of Darkness is the opening of an ancient object of extraterrestrial origin that unleashes badness into the world. And the influence the object in the pit has on the susceptible humans is echoed by the creature in the canister’s influence on the Street Schizos. Further shared ideas are that of a warning being sent through time (a device also used in Chris Marker’s La Jetée, later to be the basis for Terry Gilliam’s fine Twelve Monkeys) and the merging of the ancient with the modern: a technological explanation for the theological.

Alice Cooper actually recorded a theme song for Prince of Darkness, though it is only heard briefly in the movie. The soundtrack, as is often the case with Carpenter’s pictures, was composed and performed by the man himself in association with Alan Howarth. It’s one of their finest, low bass notes providing tension, the antithesis of a typical Hollywood score. The music is there to enhance the visuals, not to spoon-feed our emotions.

Prince of Darkness received poor notices but was a solid commercial success. Contemporary reviews totally missed the point of a smartly constructed and well-acted piece, its deceptively complex script overflowing with subtext. Carpenter uses many motifs from his own body of work. Once again we have a team of professionals fighting a malignant force. There’s the resurgence of an ancient evil, as seen in The Thing (a monster previously frozen in ice for thousands of years), 1980’s The Fog (undead lepers risen to wreak vengeance), and Lo-Pan’s quest in Big Trouble in Little China (1986). An old book provides the key to the mystery, similar to The Fog. The characters are under siege, just like they are in Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), The Fog and The Thing. Their foe cannot be destroyed, only contained (The Thing again). There’s the use of the human image to deceive, which was employed to benign effect in Starman (1984) but would later cause trouble in They Live (1988), Village of the Damned (1995) and Ghosts of Mars (2001).

Many other horror themes are present, such as demonic possession; dreams as a gateway to other realities; the genie in a bottle; the return of the repressed; the reanimated dead; evil as an infection; the repulsion of insects; stigmata (Kelly’s bruise); the mirror as a gateway to another world, or as a mirror image; and of course the Anti-Christ. Plus the film’s depiction of evil as a measurable scientific factor remains daring – perhaps too daring for some, as John Carpenter himself noted: "Critics hated Prince of Darkness at least as much as The Thing. People still deride the movie today. I remain unrepentant."

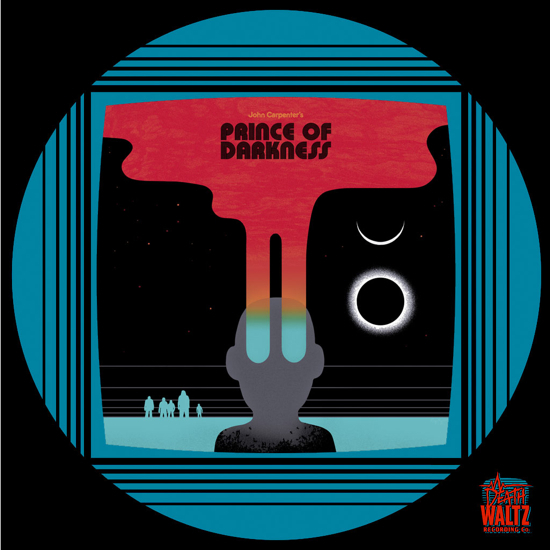

Remastered by Alan Howarth with new cover art from Sam Smith (below), the Prince of Darkness soundtrack is available on limited edition pale blue vinyl via Death Waltz Recording Company.