That slight pause, that inimitably damaged drawl. “Hello Neil.”

Hello Jennifer. Blimey. Long time no speak. Last time was 1999, near Halloween, at the Columbia Hotel in London. You wore a diamond blue hoodie, PVC trews and sky high boots and looked like the only real star in a building full of crow-haired vest-tee-wearing assholes trying to be stars. That’s about all I remember.

“At least you remember that. I don’t remember a thing.”

Has being asked about Accelerator jogged your memory about those times, 1998, and its creation?

“No, to be honest. It’s all so long ago.”

I’ve taken Accelerator and other Trux transmissions every few months, like a blood transfusion or a shot of Vitamin X. I need regular Trux to feel alive n’ degenerate in this age of deathly health n’ efficiency. How much do you listen to your old music?

“I don’t. But last year, someone was round my house and wanted to hear Accelerator on vinyl. I have a ton of vinyl. It’s all over my walls. So I pulled it out, put it on, went to another room and then through the wall I hear this noise and I’m like… what the fuck is that? Shit, that sounds awesome. Super cool. Super fresh. Still to this day.”

Goddess speaks the truth. Even in such a dazzling discography as that spun out by Royal Trux, the greatest rock ’n’ roll band of the past 25 years, Accelerator holds a special grip on your heart, a unique scorchmark on your memory. Sounds like this you don’t erase, they leave wreckage, up the ante impossibly for the future. Royal Trux bent me out of shape entirely, spoiled rock ’n’ roll forever for me. Nothing since has stood as tall, come so close, lied so true, testified so clear.

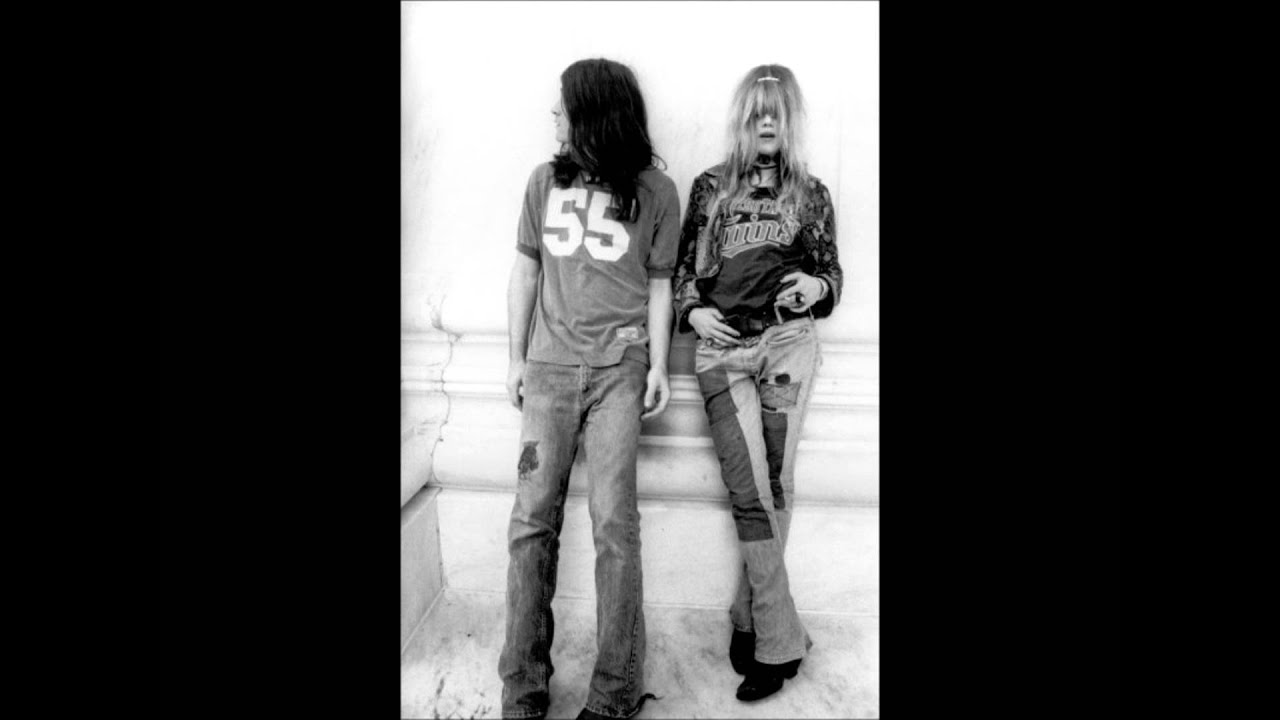

Potted legend/myth runs thusly: Royal Trux were always Neil Hagerty and Jennifer Herrema, who came together as junkie lovers in the mid-80s in NYC. Jen stripped, Neil played guitar for Pussy Galore (it was he who convinced them to cover Exile On Main St. in its entirety), broke ’n’ entered for skag money, as artists they made records that confounded sense, hustled their own universe out into yours. Their s/t debut, made in ‘87 after Hagerty had given Pussy Galore the heave ho, gave a hint that something unique was coming out of Jen and Neil’s insular obsessions (psyche, noise, bentshot blues and diseased production), grotesque music that their second LP, Twin Infinitives took to even more deranged levels of delight and intrigue, unforgettable songs played with the freedom of Beefheart, the power of the Stones, the ghostly suggestiveness of Albert Ayler. Utterly unlike any other album in rock ’n’ roll, Twin Infinitives was recorded “straight” (according to the Trux themselves) but “quality-tested” while high as fuck on weed, acid, speed and heroin and it showed, and it rocked, and that’s the way us increasingly rabid Trux-devotees listened to it too. Both the ‘mystique’ that surrounded them (rumours of on-going junkiedom and hermetic isolation that never seemed justified by their bright, articulate interviews) and the naysaying of classic-rock fans (who saw them as an entirely cosmetic agglomeration of more properly authentic sources) galactically exploded with Infinitives, follow-ups Skulls and Cats And Dogs refining and disciplining the chaos but keeping that uber-cool integument intact.

By ‘93, Trux’s sui generis style and sound had attracted the attention of the big boys and amidst a crazy bidding war Virgin snapped them up, giving them a three album, million-dollar deal. Building a more solid band-basis with a startlingly funky riddim section (Dan Brown, Chris Pyle and Robbie Armstrong) their major-label debut Thank You was produced to a choogling, garage-rock blasting-point by Neil Young’s long-time sideman David Briggs and all seemed well. Christ, they were even appearing on Friday night UK telly, a pipe bomb of genuine menace amidst the pasteurised patina of faux transgression and yooftude. Remember this? I do. It felt like… victory.

But then Trux, typically, fucked it all up by staying innocent, naively thinking that their music must keep moving on, and made one of the greatest gruesome soul-swallowing records in rock history, 1996’s densely layered, epically fucked-up Sweet Sixteen, featuring one of the most unforgettably gross sleeves ever to Velcro itself to your brainpan. Apologies if you’ve just eaten, but in ‘96 this was never gonna be at the front of Our Price stacked up next to the latest Bluetones. Those who listened to what was within, though, loved it forever. Was Sweet Sixteen an act of self-sabotage Jen?

Jennifer Herrema: “Honestly? It was a complete surprise to me how the record company reacted. People are amazed that we couldn’t foretell it, but we lived in our own warped little world in Royal Trux, all the way through. It only seems inevitable in retrospect.”

I remember being sent Sweet Sixteen for review. It was like being handed contraband or something. Under the counter, down a dark alley, slipped under the tongue to fizz and freakacize you. Barely a press release. Which seemed astonishing for a record that had so clearly taken so much work – Trux’s sound on Sweet Sixteen found itself elaborated to a multi-layered fugged-out heaven, strings, solos, songs so grubbily, groggily great you wanted to permanently crash their party, making damn sure they never set foot past your own threshold. Virgin absolutely shat themselves, sought escape routes from this derangement arrangement.

“To me, it was just a rock album. We didn’t make it in defiance of anything or as some act of bratty retribution. We just thought it was cool. You got to remember, with the money Virgin had given us we’d built our own studio on our ranch in Virginia. We were kind of… cut off from reality, from the radio, from what music was ‘happening’. We lived in our own special world. We made the record and sent it to the label. The sleeve, to me, just seemed to suit the music, it wasn’t intended to shock. It just seemed to reflect the music, so the whole thing was one neat tied-in package – like I said, we were in our own odd little alternate universe. We sent it to them. Then we just didn’t hear from them. Absolute silence. For a long long time.”

“I don’t like this arrangement / Your wild schemes are nothing but pipe dreams / I don’t like this arrangement / And we can’t win without the kid / We need somebody / Somebody to watch our backs”

Did you ask what was going on?

JH: “Well our manager – another thing that Virgin gave us, a proper, ponytailed, Armani-suited manager – let us know that basically the label were freaking the fuck out about the record. We were so naïve: ‘what? Really? Why? It’s so cool!’ And for so long the record was just in this kind of limbo. We were done with it, and the label didn’t know what to do with it. They then decided to do the bare minimum they could with it, fulfil their contractual obligations by putting it out, but putting absolutely nothing into distribution or promotion. They were embarrassed by it basically, didn’t get it at all.”

Trux were always massively naïve/innocent musically, sharp as fuck in a business sense. They rapidly realised that their label’s fear could be to their advantage.

“Basically they wanted us to go away quietly. Which we were happy to do, ‘cos we had their money. We had a three record deal which basically meant they had to fund the recording of the next album. Initially, Virgin were like ‘you need this producer, and this look, and this kind of marketing’. But after Sweet Sixteen they were so horrified by us, they just wanted rid of us entirely, didn’t care when we said we wanted to record the next album ourselves and put it out on our old home Drag City. They wanted out which suited us fine. We ignored them the best we could, and made Accelerator.

Ties weren’t completely cut. Trux no dummies. They got their money first.

“We were under a three album deal. They had to fund the next record. We got £300,000 to make it and made it for a hell of a lot less than that ‘cos we produced & recorded it ourselves.”

Before making Accelerator did you and Neil discuss what you were going to do with the record? Even though you had the smokingest live band on the planet, it never seemed like Trux ever saw recording as an attempt to merely ‘capture’ that.

JH: “Well, we set ourselves parameters to ensure it’d never be like that ‘cos that didn’t interest us, and seemed impossible anyway. The loose concept around the three LPs we’d make for Virgin was that each one would kind of cover a decade of music. So Thank You had short songs, a real garage-rock vibe, real 60s sentiments and sounds. Lo-fi, which became this kind of badge of pride for so many bands, was something we were basically forced into early on, out of necessity, poverty, running in and out of other people’s studios. Sweet Sixteen you’ll notice had no songs that were under about four-and-a-half minutes, and that was our homage to the 70s, to the kinds of songs that’d be played only on FM radio. In both Sweet Sixteen and Thank You and Accelerator it wasn’t that this concept of decades was a real straightjacket, it was a loose concept, but it focussed things so we could utilise signifiers and to a certain extent have our choices dictated to us.”

So Accelerator was all about the 80s?

JH: “Well, in a way, yeah. To us, the 80s were a time where music was actually full of melancholy, full of mood and yet it was always put under and behind music with a real pop sheen to it. We needed to find a way to do that ourselves, and then this miraculous thing entered into the equation. We’d outfitted our studio ourselves. We didn’t ‘use’ our kit correctly really, we kind of abused it with a total innocence, forced all the parameters to the max just to see what would happen. Even if our starting point was theoretical, songwriting was always a playful thing. And into this, because we bought one just to see what the hell it did, comes the spectrum analyser. And everything changed as soon as we started to use it.”

Pardon my ignorance. What would that be, what does it do and what possibilities did it open up for you?

JH: “Hey, we’re analogue people. But the spectrum analyser we thought was amazing. It looks at sound and turns it into something visual. It basically gave you this ability to SEE how pop works. We started feeding it pop hits: Britney, Spice Girls. It was amazing to us that this thing actually enabled you to visually see a pop hit, chart exactly how one works and what it consists of. We’d already recorded the songs on Accelerator it was all mixed and we’d been listening to it all for ages. But then me and Neil thought – what if we ran our music through the analyser and squashed it and compressed it all and forced it to conform to what the analyser said made a pop hit. When you can see the waveform, you can line it up. And what we found was that we got some incredible sounds by forcing our music through that process. We got the sound of pop radio, but a kind of very distorted, extreme kind of pop radio that only plays Royal Trux songs!”

So did you submit entirely to the will of the machine?

JH: “No, we never did that; always at root, alongside all the thought and concepts, were our gut instincts which were usually powerful and usually right. But by having that process of removal and remix, we got some distance from the songs, started enjoying them again and found ourselves able to really accentuate those moments that stick in your memory. The crucial thing always was to move on. Unlike an awful lot of bands who’ve claimed us as an influence we’ve never really been happy with a niche, or been able to ‘stick with’ or ‘hold on’ to any aspect of Royal Trux. It’s something nearly all new bands try and do, find themselves a clearly defined ‘market’ and find security in that. Just not the Royal Trux way. I get bored real quick. There was no way Accelerator was ever gonna sound like anything else either we, or anyone else, had made.”

Indeed, Accelerator, unlike nearly every single re-imagining of the 80s that’s come since (and in recent years they’ve been coming thick ‘n’ fast ‘n’ mainly very, very thick) achieves that uncanny trick that all Trux music does – it makes you believe again that rock music can communicate the whole of experience again, even those tiny frauds and massive fictions that our memories and musical consciousness are made of. You’d be hard pushed to find an 80s record that sounds like Accelerator but at the same time, in its gurning grotesquery, its ear-splitting sheen, its constant breeding of omnivorous giant earworms in your soft skull, it’s closer to the horrors and naiveté of 80s pop than anything else that’s come in its wake. Where so many bands, then and now, try and erase technology in a misguided attempt to achieve their false notions of a purified musical past, Trux used technology to break rock’n’roll down, reconstructing it with a fully wonked-out, wacked-out geometry that was utterly unique, unique because it was technology being used by the unique imaginations of Herrema and Hagerty (on their startling remix work they called themselves Adam & Eve – check out their rerub of V-Twin’s ‘Delinquency’ if you haven’t before). On Accelerator, certain sections of your headspace get filled in, blitzed, emptied, ringing with resonance and echo, seething with tinnitus, no bleed between elements, sticklebrick rock. And always always Neil and Jennifer’s voices, immutably cool, pulling together the sprawling and wasteful into three minute-models of concision. It’s the closest rock music got to a RZA production in ‘98, and it still sounds utterly fucking awesome.

JH: “I grew up on hip-hop so that thing of kind of attacking what you’ve recorded after the event was totally natural to me. We were both into dub as well. All those songs were recorded, like, minimal amount of takes. Then layered. Then butchered. It didn’t seem like some big statement at the time, but it felt good to be ‘free’ of the major label restrictions. I mean, we had full artistic control at all times, but with Accelerator we knew that the label weren’t even going to attempt to rein in what we were doing. Lyrically there’s lines on Accelerator that, looking back, are precisely about our circumstances back then. Totally subconscious but a symptom of how we felt. That’s why Accelerator is still something I’m so totally proud of. Not only ‘cos it still sounds so fresh, but because it was the moment we broke free. From then on, no-one was in control but us.”

Trux’s last two albums, Veterans Of Disorder and Pound For Pound, the massive and mind-blowing triple collection Singles, Live, Unreleased and their astonishing final few tours saw their influence grow, something that hasn’t subsided since the band called it a day in 2001. Oddly I never see anyone copying the odder, more idiosyncratic elements that made Trux so special, let alone manage the crucial generosity of spirit and blank-faced intransigence that the Trux so simultaneously made their own. Like the way Neil played through a tiny box amp with what looked like a guitar from the Argos catalogue, but could still seemingly conjure up heaven and hell at 200db/mph. Like the way Neil used to start every gig by wiping every microphone with disinfectant wipes. Fabulously un-rock’n’roll.

JH: “Man that used to drive me crazy! I had to send back so many AKG 535s because the bleach had penetrated the diaphragm! He was, and still is, an eccentric. And is still the greatest guitar player I think I’ll ever get to work with.”

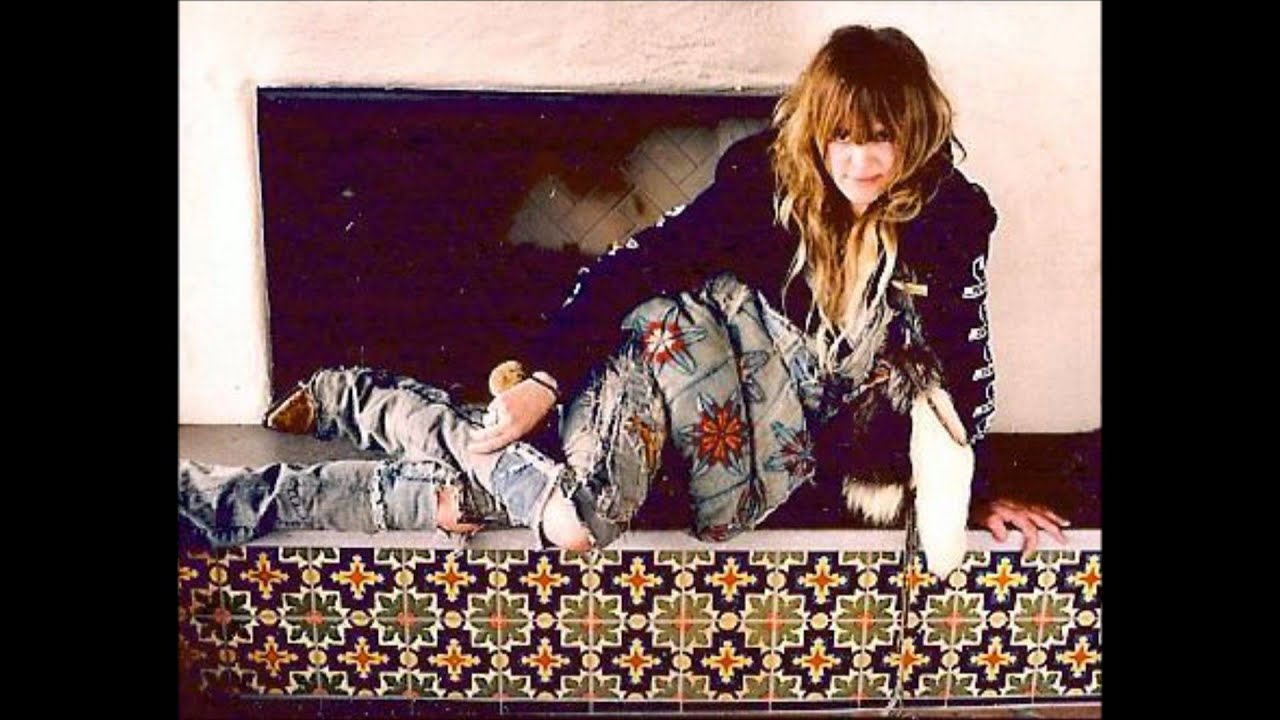

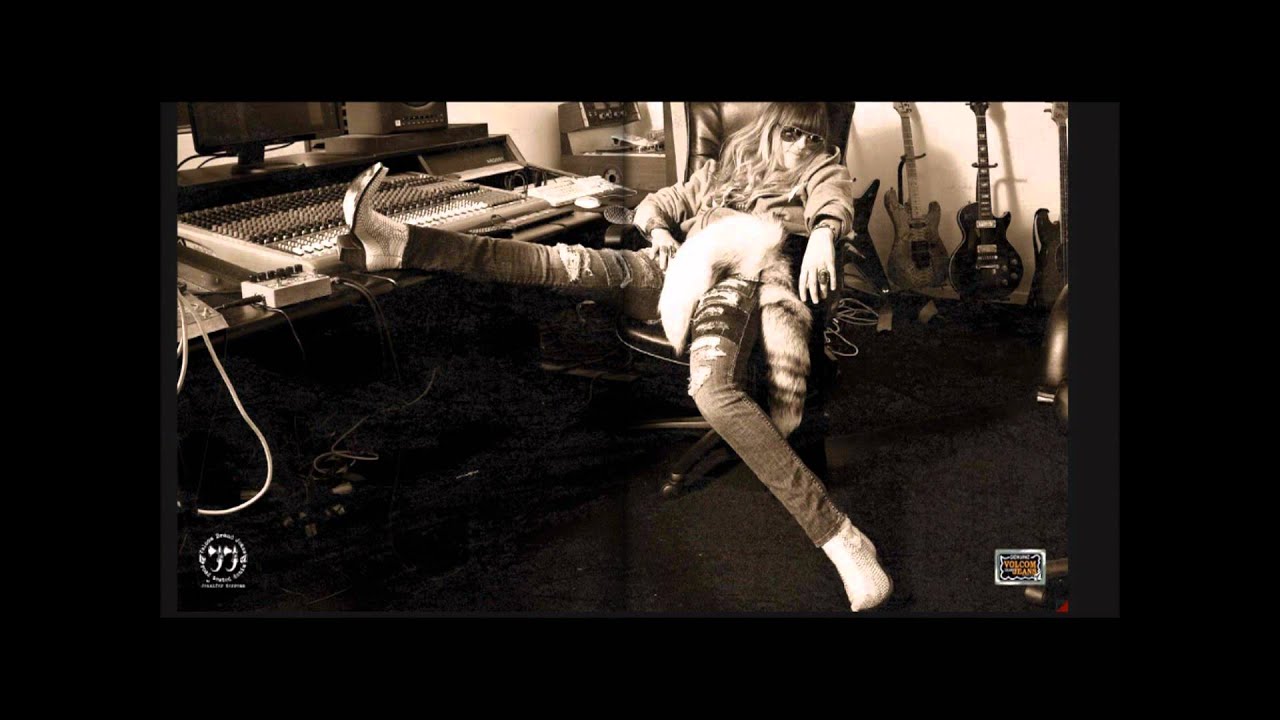

Neil’s post-Trux work with Weird War and the Howling Hex has been sporadically incredible. Currently involved in both fashion (last year she designed the ‘Road Tested Denim’ range for Volcom and continues to design skate and surf wear) and music with the stupendous Black Bananas, Jennifer is also still an evergreen inspiration to anyone willing to get blessed by her work – do you hear or see many bands who’ve clearly borrowed from Trux, Jen?

JH: “Well, strangely, yeah, but things that happened to us by accident, our look and our sound, these bands seem to have turned into a marketing ploy. I mean, I think it’s fairly safe to say that a band like The Kills simply wouldn’t fucking exist without Royal Trux. But there’s a crucial thing they miss. When we used to tour… I mean, I remember touring with Primal Scream and those guys were fucking amazing, every night would be totally fucked up, a total party, purely about having fun. My current band, Black Bananas have toured with The Kills and it’s like… so fucking polished and slick, the total antithesis of Royal Trux, even though it’s clear that Allison and Jamie have borrowed a lot of their style from me and Neil. To be honest, I found them deeply boring after a while. I mean, don’t get me wrong, they run their shit like a military operation but as each show approached it’d be like they were on some sort of strict clampdown. And that kind of niche-marketing extends to their music. They’ll never sound like Royal Trux. Trux were about telling it like it is and having fun.”

Get Accelerator, go backwards, forwards from it. If you ain’t got any Royal Trux in your life, now’s the perfect time and opportunity to find redemption. Will you ever work with Neil again?

JH: “Ummm… not today! Never say never though. Who knows? Not us. Trux is done really. But I’ve learned never to try and predict what trajectories your life will go on. Could happen. Might not. I’m not the person to ask!”

Telling it like it is. Having fun. Long may Trux’s supreme isolation continue. The greatest rock’n’roll band in the world. Still to these ears, undeniable.

Jennifer’s new band Black Bananas can be found here. The Accelerator reissue is out now on Domino; for more details, head here.