While it is now generally regarded as one of the Italian horror director’s most accomplished films, upon its initial release in 1982, Dario Argento’s Tenebrae was so reviled in the UK that it found itself cut to ribbons and relegated to the ‘video nasty’ list. Now recognised as a slyly reflexive and deconstructive commentary on not only Argento’s own body of work but also the conventions of the Italian giallo, Tenebrae has experienced a critical reappraisal because of its underlying theme of the effects of violent entertainment on audiences. The twisted tale of an American mystery thriller novelist who becomes caught up in a slew of sadistic murders, seemingly inspired by his latest book, Tenebrae marked Argento’s return to the giallo after a successful detour into the supernatural gothic horror of Suspiria (1977) and Inferno (1980).

For the uninitiated, giallo (plural: gialli) is Italian for ‘yellow’. The term’s application to a particular cycle (‘filone’) of Italian genre cinema popular throughout the 1970s originates from the trademark yellow covers of mystery and crime thriller books by the likes of Agatha Christie, Cornell Woolrich and Raymond Chandler, first translated and published in Italy by Mondadori Press in the 1920s. It’s an Italian catch-all phrase for ‘thriller’. When applied to cinema, for English-speaking audiences, the term denotes violent mystery thrillers instigated by Mario Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963) and Blood and Black Lace (1964), and popularised by Dario Argento’s 1970 debut The Bird with the Crystal Plumage. Generally speaking gialli boast serpentine whodunit narratives, titillating scenes of sex and nudity, lavishly choreographed murders, and a startling amalgamation of exploitative violence and art house chic.

In the wake of the international success of Suspiria, the diabolical tale of a young ballet student who discovers her dance academy is a front for a coven of evil witches, Argento spent some time in the States where he began working on the sequel, Inferno. While there, he became the target of an obsessive fan’s attention, and what began as ‘enthusiastic’ admiration soon became something much more sinister, with the director at the receiving end of several death threats. This ignited the spark of an idea about an artist being persecuted because of their work, and after the commercial failure of Inferno, due in part to problems with distribution and studio interference, Argento refrained from completing his witch-infested ‘Three Mothers’ trilogy and opted to return to the conventions of the giallo for his next project.

Despite its title, Tenebrae (Latin for ‘darkness/shadows’) is a surprisingly bright, starkly lit film. The cinematography, courtesy of Luciano Tovoli, who also photographed Argento’s psychedelically nightmarish Suspiria, enhances the cutting edge style and semi-futuristic feel the director was striving for. While the story unfolds in Rome, it is not the picturesque Rome usually portrayed in cinema; no obvious landmarks or typically baroque architecture are featured – it is presented as an anonymous, quasi-futuristic city full of high rises and sparsely populated spaces. According to Tovoli, Tenebrae was even tougher to light than the candy-coloured hell-world of Suspiria, but the result is visually striking. Almost every scene plays out under ubiquitous glaring lights as it soon becomes clear that the ‘darkness’ of the title actually refers to that which lurks in the human psyche. The movie is awash with red herring characters – all of whom have motive to kill, and enough ambiguity to appear guilty – while the shocking denouement reveals that there was not one, but two deranged killers.

Argento’s typically prowling camera work is also on fierce display throughout Tenebrae. It stalks after wide-eyed, hapless victims, aligning us with their point of view as well as that of the killer. In one stealthily voyeuristic sequence it actually scales a victim’s house in a single seamless take; navigating walls, roofs and peering in through windows, not only demonstrating the penetrability of the seemingly secure abode, but the director’s technical prowess. This breathtaking moment was achieved with the utilisation of a Louma crane, specially imported from Paris, and marked the first time such equipment was used in an Italian production. This shot also serves to highlight to the audience their role as spectator, and is one of a number of carefully orchestrated moments which work to momentarily lift us out of the narrative. Throughout the picture we witness events from many oscillating perspectives, resulting in a dizzying malaise of voyeuristic creepiness and the implication that the deaths depicted within the story are ultimately for our entertainment.

As well as tipping his hat to literary influences such as Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, Mickey Spillane, Rex Stout and Ed McBain, Argento also explores some of his most reoccurring themes and preoccupations, such as Freudian psychology, sexual deviancy, repressed trauma, voyeurism, audience spectatorship and the fetishisation of violence and death. Despite all the slyly subversive commentary, Tenebrae also functions as a purely engrossing, slickly executed murder mystery, with a great cast of genre stalwarts and more twists and turns than you can shake a glinting switchblade at. Anthony Franciosa stars as tortured crime writer Peter Neal, providing one of the sturdiest leading roles in any Argento film. He’s flanked by Argento’s partner and muse at the time Daria Nicolodi, whose voice was dubbed in the international version by Theresa Russell. John Saxon, making his return to the giallo twenty years after staring in Mario Bava’s seminal The Girl Who Knew Too Much, also stars as Neal’s unscrupulous agent Bullmer, who is having an affair with the author’s fiancée Jane, played by Silvio Berlusconi’s estranged wife Veronica Lario.

Tenebrae boasts an equally stylish and progressive rock score courtesy of Goblin members Claudio Simonetti, Fabio Pignatelli and Massimo Morante. Reliant on vocoders, synths and electronics, it not only accompanies the scenes of stylised violence, but at various points also functions within the plot itself. In the scene where Tilde (Mirella D’Angelo) yells at her girlfriend to turn off the music, which we had assumed was merely the soundtrack of the film, the girlfriend eventually lifts the needle from a record player and the music, diegetic and non-diegetic, instantly stops.

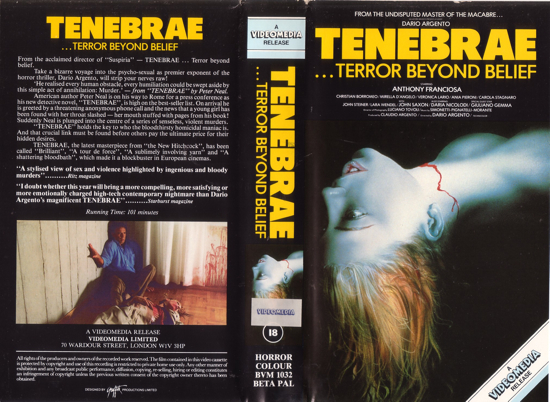

Released theatrically in Italy and throughout Europe, Tenebrae fared less well in the States, where it was heavily cut, re-titled Unsane and not released until 1984. The edited version sought to tone down the violence, but various scenes which established character dynamics and plot development were also heavily trimmed, rendering the narrative incoherent and contributing to the movie’s negative reception. UK censors also hacked at Tenebrae prior to its theatrical opening, and went much further by the time it was released on VHS in the midst of the video nasty maelstrom. It was one of 39 titles prosecuted and banned in the UK under the Video Recordings Act 1984, which deemed these particular films as harmful to audiences. This is ironic given that Tenebrae is a highly reflexive work in which Argento addresses themes concerning the culpability of violent entertainment on society, misogyny and the conventions of crime thriller narratives. The ban lasted until 1999, when Tenebrae was re-released on video, but with cuts intact. Finally, in 2003 the BBFC reclassified and passed it uncut.

Perhaps the main reason why Tenebrae fell foul of the BBFC in the first place was due to the highly sexualised presentation of its violent content. Throughout the movie a slew of beautiful female victims exhibit an almost sexual response to having sharp implements thrust into their vulnerable flesh, and their savagely slashed bodies are subsequently strewn about in morbidly exquisite poses rather akin to a Helmut Newton fashion shoot. Argento’s fetishisation of weapons and murderous implements is also rife, particularly in the flashback sequences featuring a woman ‘orally raping’ a man with the heel of her bright red stiletto. Indeed, author and critic Maitland McDonagh noted: "Tenebrae is fraught with free-floating anxiety that is specifically sexual in nature." As mentioned, the twisted plot features not one, but two killers. The motive of the first killer, Cristiano Berti (John Steiner), the highly conservative TV presenter who interviews Neal about his work, enhances the psychosexual nature of the murders. He is on a ‘moral crusade’, inspired by Neal’s latest novel, to cleanse society of those he considers to be morally depraved. Decked out in the typical giallo garb of black leather gloves, he kills a series of sexually liberated women because of his warped perception of their ‘perversions’, dubbing them "filthy, slimy perverts". He uses literature to lend credence to his bloody antics. The second killer, revealed to be the author himself, has a series of Freudian flashbacks which expose how the misogyny evident in his books actually stems from being sexually humiliated by a beautiful woman in his youth.

Nowadays the film has transcended its initial reputation as a sadistically sleazy video nasty and is regarded as a cunningly reflexive commentary on the nature of violence in cinema and literature. Throughout the running time, the director – who has in the past made inflammatory statements such as, "I like women, especially beautiful ones; if they have a good face and figure, I would much prefer to watch them being murdered than an ugly girl or man" – addresses the accusations of misogyny he has faced throughout his blood-spattered career. Critics have suggested that the character of Peter Neal, a purveyor of violent literature, serves as an alter ego for Dario Argento. A number of telling debates between characters about violence and misogyny in cinema and literature unfurl as Argento reveals his own opinions about such matters. When questioned by the police after pages of his book are found stuffed into the mouth of one of the victims, the author exclaims: "If someone is killed with a Smith & Wesson revolver do you interview the president of Smith & Wesson?" When quizzed by Tilde about his alleged misogyny, he replies that he "loves women". Argento’s own gender politics also seem completely misogynistic, but they are never actually rigidly polarised. His stories rely heavily on strong female characters and, quite often, men with ambiguous gender identity. Tenebrae‘s flashbacks feature a woman who sexually humiliates the killer. This woman is actually portrayed by transsexual actor Eva Robins, echoing the character of Carlos’ transvestite lover in Deep Red (1975), who was portrayed by a woman. This subversive casting showcases Argento’s interests in gender, and the obtuse line that often defines it.

Interestingly, while Argento seemingly goes to great pains to address and dissect the notions that violent entertainment has a harmful impact on its audience, at the film’s climax it is revealed that the author is the second killer; the purveyor of violent novels who all along claimed that there is a definite line between reality and fiction. While the first killer’s murders paid homage to Neal’s works of fiction, the murders Neal carried out were his fictionalisation of reality. Far from undoing the film’s reflexivity, this highlights Argento’s morbid sense of humour, and opens a coy and labyrinthine commentary on the relationship between art and life, and how the two can often reflect each other. He even commented: "After making all these films, I would probably be a pretty good murderer."

Of all the titles placed on the video nasty list, Tenebrae is perhaps the most misunderstood and undeserving of the grimy status it gained through its association with the whole debacle. Its crafty reflexivity and deceptively intellectual subtext were overshadowed by its stylised violence, which brings to mind Quentin Tarantino’s quip: "As a filmmaker, when you deal with violence you are actually penalised for doing a good job." Indeed, while most of the video nasties have been subsequently reviewed and released to DVD with varying cuts implemented, none – with the arguable exceptions of The Driller Killer, The Last House on the Left, I Spit on Your Grave and Cannibal Holocaust – have received the kind of critical reappraisal afforded Argento’s Tenebrae, now also considered to be one of his last great films.

Dario Argento by James Gracey is published by Kamera Books.