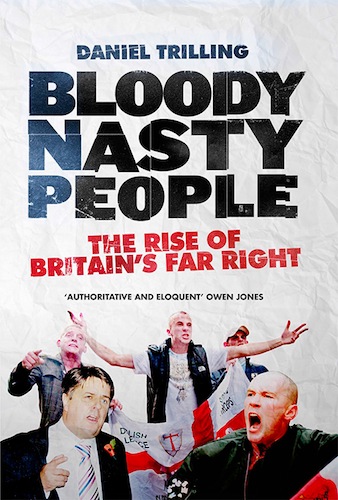

Bloody Nasty People: The Rise of Britain’s Far Right is the first book from New Statesman journalist Daniel Trilling. Plotting a clear course for far right politics, from the birth of the century to the present day, Trilling’s aim is always to understand and to interpret a world in which most of his readers will fascinated but also far removed. While unashamedly written from the point of the left, Bloody Nasty People is not a polemic and, to the author’s credit, never seems to stray too far in to that often divisive territory.

In the vein of Iain Sinclair and Owen Jones, Trilling seeks to entertain as well as inform; working carefully with a dangerous and particular kind of alchemy the author has transformed a broad and incredibly dense subject matter in to a book that is, both, didactic and gratifying to read.

What is it about the Far Right that fascinates you – what was the impetus for writing this book?

Daniel Trilling: I suppose that the most immediate reason is that I had already been writing about the BNP for The New Statesman for several years. That began out of a very basic curiosity: why were they winning votes? I started in to a more detailed report in 2009, a period where it did seem to really be on the up and gathering steam, and it seemed likes efforts to push them back just weren’t working at all; I was interested in what it really meant for a town to have an embedded presence of these people – the first thing I did, for example, was go up to Stoke-on-Trent, I’d read a in The Guardian about how they had nine councilors and were the largest opposition group on the council, to find out how it actually played out in daily life.

So I followed that for a for a few years, wrote some more reports, and then chance to write the book came up. I was still curious enough to want to do it and to really want to understand what the BNP was, what the ideas of the people at the heart of it were, and also why they were appealing to people outside of that little circle of the far right.

You’re coming in to this looking to “understand it,” but people – particularly those who know you write for The New Statesman, might question your objectivity and wonder about your own agenda; how do you think it’s played out?

DT: Well it depends what you mean by “objectivity.” I certainly don’t treat them in a way that suggests that their opinion is as valid as anyone else’s – I don’t have that notion of balance.

In the introduction you apologise for bringing Nick Griffin in to a pub, for example…

DT: This – fascism – is obviously something I very strongly oppose and I expect most of my readers will as well; but there was a real need to understand – what were their ideas, what was their project? Obviously it was appealing to people. Something I try and make very clear in the book is that there is a real distinction between the people that run the BNP or other far right parties of a similar sort, with a very defined world view based on very extreme biological racism and conspiracy theories about how Jews secretly run the world and so on, and your average BNP voter – someone who probably doesn’t share those ideas. At least not at first. There’s something bigger going on: for them to win any votes they’ve got to appeal to people outside of their own little circle, and when that starts having success (as it did in the last decade) it suddenly raises the question of “Why?” – what’s going on elsewhere in society that is enabling this to happen?

As you were saying before, “ordinary people” make up a considerable number of BNP voters; the non conspiracy theorists and people who wouldn’t consider themselves to be fascists, or even racists. Do you think readers of the book will be surprised at how these people come across?

DT: I’m a bit wary of that idea of “ordinary people” – it’s a construct – everybody thinks they’re a normal person; even people in the BNP think they’re reasonable. What I really wanted to show is the story of the BNP: after Nick Griffin became leader in 1999, what you saw was his intent to put into practice a set of ideas that he and a group of other people had formulated – how they could turn what had been a very marginal far right party that engaged in kind of violent street politics in to a smart, outwardly respectable, election winning machine that would replicate the kind of success the French Front National had at the ballot box. And to do this they had to win support among voters who were not immediately inclined towards their core beliefs. So, what I do in the book is visit towns where the BNP had their greatest successes and try to speak to both sides – to people in those towns, some of whom voted for the BNP and some of whom tried to oppose it. I wanted to build up a patchwork account from different people’s views of the same events to try and really get at the truth of what had happened.

I think once you start building up the picture you see how much it’s a result of people being pushed by racist attitudes that are already just present within society, other economics things – resentments about housing or whether people feel that they’re getting a fair share of regeneration money – whether people feel like they’re being pushed out by the main political parties. All of that can come off sounding quite abstract – quite dry and theoretical – but these are every day concerns for people. Yes, I want to make clear arguments about why the BNP had success and what’s gone wrong elsewhere in the political system to enable that, but I was constantly asking myself “Okay, but what does this mean in every day life? How does it actually play out? How do people live this stuff?” And that meant having to speak to BNP members and voters and not recoil in horror the moment they told me any unpleasant thing. They might believe in this thing that I find awful, but they also live it: what does it mean to be a fascist but also be a grandmother?

It’s not a dry book – in fact there have been a few similar politically-based books recently – yes, there’s focus on the data, but it has a clear and driving narrative…

DT: I think it’s really important, if you’re writing as a journalist particularly, your audience is there voluntarily – it’s no good if no one reads your book. I don’t have the resources to do a work of academic rigor, it needs to be read, it’s not like an academic book that can sit in a library and be a resource as and when; it plays a different role. I think that’s the difference between journalistic and academic writing,: there’s more competition for readers attention. But, also, I like telling and structuring stories. I have perhaps a naïve belief that if you can turn something as horrific as this in to something that makes sense then it’s going to improve things – you know?

Those other books – Ian Sinclair’s Ghost Milk and Owen Jones’s Chav, for example – have also sold well. That hasn’t always been the case: why do you think political books are gaining that kind of popularity?

DT: I think it’s the times, really: people are living in a much more chaotic and unpredictable period, politically and economically and people are quite understandably looking for things that will give them answers – or give them tools for understanding. That makes it all the more important that there are people who can step up and offer those things. People read stories to give them pleasure to read and – when you’re dealing with difficult material, particularly – you have to structure in an way that eases people through. The reason you choose a narrative form for writing is because it can get at a truth that other forms won’t.

I think if I’d just charged in to the book and said “right: here’s what I think about everything and here’s how it happened” it would’ve been very deadening and wouldn’t have given the reader much of a chance to think for themselves – they’d have just had to take it or leave it; agree with me or put the book down. Instead, what I’ve tried to do as far as possible is let people tell it through their own words. But it’s tricky – you want to stay in charge as a writer – these people aren’t literally telling the reader their story in their own words; it’s filtered through the writer. I couldn’t just open the field open and let anyone say whatever they wanted to, because some of the voices in the book are fascists and you can’t just give that a platform. It’s a test of how subtle you can be.

Do you think that people who pick up the book who don’t know a great deal about politics, perhaps looking for a grounding or an understanding in the way you’re looking to provide, will be surprised when they look at the history and the Lib Dem influence on the right wing in context with today’s politics?

DT: I think people of our generation will be surprised; people a bit older will remember that episode. But I really wanted to show the BNP related to mainstream politics; how failures in the political system allowed the BNP to operate. But I didn’t want it to be a kind of crude finger pointing – so when I show how Liberal Democrat campaigning in East London in the 1980’s paved the way for the BNP to win a seat there, when I show how things that the Tories said about immigration in the 90’s contributed to their rhetoric, or about how statements made by Labour ministers in the early 2000’s legitimised the ground on which the BNP was campaigning – it’s not in the form of “Oh aren’t they terrible people? Let’s just deplore them.” I wanted to show that you can’t give a nod and a wink to something, basically to racism. The idea of “If I just take on a bit of that racism that’ll bring them towards me and it’ll stop it from getting any worse” – I just think that’s a suicidally wrong impulse. All it does is makes the whole political debate more racist and I just wanted to show how that works in miniature – with the Lib Dems in Tower Hamlets, for example.

But then you get to the end of the book and it’s happening on the national stage with Griffin’s appearance on Question Tme. And I think that gets to the heart of what’s so damaging about far right groups – they may only have a relatively limited amount of political success – they have no real executive power or real political influence – but their presence on the political landscape risks skewing everything else on to the ground that they occupy, and I think Question Time was the biggest example of that: Griffin himself was a disaster, but you had a half hour with all the mainstream politicians climbing over one another to be tough on immigration, saying “We understand why people vote for the BNP,” but never addressing the fact that it was the governments own policies that were pushing the BNP support up.

Where does the EDL fit in to all this?

DT: A large number of BNP activists moved over to the EDL when it really got going – partly because it provided an outlet for the kind of street politics that the BNP had suppressed because it needed to sanitise its image. I think that’s one of the reasons why it grew so quickly. I think also it represents quite a crucial shift in ideas; where the founding ideology of the EDL is this hatred and abject fear of Islam, the same kind of ideology that Anders Breivik claimed – so those kinds of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories don’t underpin it in quite the same way. That potentially means its got much broader appeal.

I think that there has been quite a lot of confusion around the EDL; I think people were quick to say “Oh, no, they’re completely different to organisation to the BNP; they’re not fascist, they’re not even racist because it’s just Islam they’re protesting against,” but I don’t agree with that analysis. Anti Islam sentiment exists in a far wider range of British society than just the far right – it ranges criticism of religious customs and practices to outright racism – there’s a whole kind of spectrum of it. And if you look at the particular way in which the EDL use it, it really fits in to the way that fascist groups have always operated: they’re saying “There’s a threat to our nation – there’s a foreign body within, we need to remove it, we need to kind of purify ourselves by removing this enemy within,” and it really ramps up the threat to irrational levels. If you look at the EDL propaganda, it’s all about how Muslims are going to take over Britain and they focus on very bodily things – halal food, sex – this idea that all Muslims are predatory pedophile rapists or that they’re trying to marry and convert white women.

Where do women fit in to the whole equation?

DT: Fascism is misogynistic but, at the same time, women have always been present within fascist movements – the first British fascist party was founded by a woman in the 1920’s, for example. The groups are dominated and run by men, but they will use women often as a way to soften their image: Griffin for example, when he took over, he revamped all of the BNP’s publicity material with images of their female candidates.

The other way in which it’s often used, and the EDL has had more success with this, is the way in which women’s rights – and LGBT rights, for that matter – are mobilised against Islam. They even have what they claim is an LGBT division – they have a few people that have joined them that wear pink triangles on their clothes at demonstrations, which is the symbol the Nazis made gay people wear in concentration camps. But, again, that whole rhetoric – they didn’t invent it – this has been rampant within the British media for at least the last ten years; you could see it being mobilised on the war in Iraq for example in the idea that Muslim countries are “backward” and therefore we need to go to war with them to impose our superior values.

Do you see any link between their position and the overseas wars; as troops withdraw from Afghanistan, for example, are people less inclined to think of Islam as the enemy?

DT: Strangely, if you look at the BNP’s attitude to the wars it has always staunchly maintained that it’s an anti-war party, or so it says. And I think it tells you something about the nature of British racism: it’s really changed in the last fifty years from the imperialist “white man’s burden” ideology that says we are a superior race and we must go out in to the world to conquer and to civilise. When that became increasingly out of reach you saw this shift in the British elite toward amore inward looking, fear driven, racism that was given it’s most prominent expression by Enoch Powell.

The end of wars abroad may not put an end to Islamophobia, although – yes – the war on terror may have exacerbated that, but we’re moving now in to a period where Britain has to deal with what it’s done and the knock on effects of that.

Bloody Nasty People is available now on Verso Books