It’s ten years since I sold the last of my Frank Zappa albums, three since I started to regret it. Or rather, not regret it but hanker after buying a few of them back. Why? The way I see it, nostalgia is a disease. For those seven years when I felt his music had no relevance to my life pulling out one of the albums would have been malingering. Unfortunately, by the time I listened again to discover, actually, his music was more relevant than ever, the music was pretty damn difficult to find.

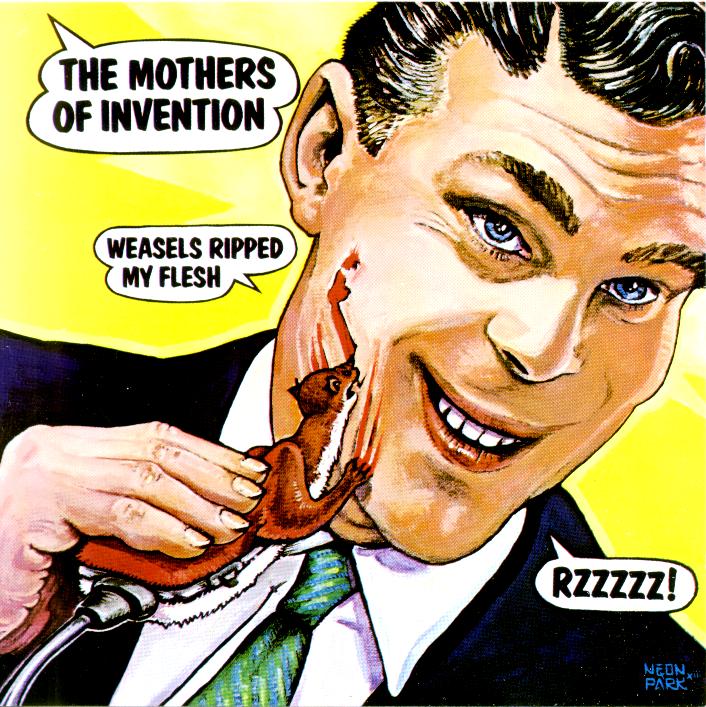

Especially the early stuff. Take Weasels Ripped My Flesh, chronologically the ninth of these re-issues and at one point an album I’d claim to be my ‘FAVOURITE ALBUM OF ALL TIME’, by any artist, in any genre. Originally released in 1970, I was lucky enough to acquire a vinyl copy in the early 90s from someone who thought it was a horrible atonal mess (rather than the beautiful atonal mess it actually is). Once I’d worn that out I bought the CD.

Big mistake. I’d have been better off saving up for another vinyl copy. Zappa was someone whose career could be considered a tragedy in the purest sense. A classic workaholic perfectionist, obsessed with recorded sound, he was quick to grasp the fundamental differences between vinyl and CD. Deciding that his entire catalogue needed revising to meet the needs of this new medium, he spent an indecent chunk of the last nine years of his life creating a discographical nightmare. Weasels lost a couple of essential seconds at the climax of one track, replaced by three decent but irrelevant minutes that totally disrupted the flow of the album. It’d been subjected to a clumsy remix, smothered in reverb to disguise tape hiss then botched through some nasty filter that seemed to deposit wow and flutter randomly, like a kitten had been playing at one end of the mixing desk. Yet Weasels escaped lightly compared to We’re Only In It For The Money and Cruising With Ruben And The Jets, both of whom ended up with entirely new bass and drum tracks.

Some people might think this is the kind of thing Zappa fans relish, think we’re the type of perverts who actually get off on it. Any Zappa disciples who haven’t read Ian Penman’s classic 1995 anti-Zappa rant in The Wire should head over to their online archive now to see what the plastic people think of you. Got it? Looking for "get out clauses from the idea of simple plain fun"? Wanting to "collate and collect and fanzine-date each and every guitar solo into cultural, slo-death oblivion"? Nah, not me matey. I just want to play the music loud without feeling too queasy.

And now I can. And so can you do too! This latest re-issue campaign, the second since Zappa’s death in 1993, marks the first major posthumous attempt to repair the worst of the damage inflicted on his catalogue in the 80s and early 90s. Hopefully it should also mark a resurgence of evangelism by the Zappa massif, a chance to whole-heartedly recommend his most accessible works in unbotched form, to refute the most heinous lies peddled by the likes of Penman and his misguided brethren. Not everything has been restored, but the majority of Zappa’s pre-digital catalogue will finally be available once more in a form somewhat close to what was originally intended.

Note the qualifier. Not everything has been restored. Not all of the tinkering Zappa did was incompetent, some of it was merely tasteless. One album remaining in remixed form is The Mothers Of Invention’s debut Freak Out! from 1966. Never one of my favourite albums, it really doesn’t bother me so much that Zappa decided it’d be a good idea to tweak the drums so they’d sound like they were jacked from a session by Huey Lewis & The News. It may bother those who think this is an album of historical import, pivotal not only in Zappa’s story but the LA freak scene it documents. They’ve got a point, but in either edition Freak Out is, bizarrely, too timid and polite to endure unscathed into the twenty-first century. The first half is a knowing but mediocre psychedelic pop record. The second half is more assured, especially the square white funk of ‘Help I’m A Rock’ and the genuinely sinister serial killer posed barbershop quartet of ‘It Can’t Happen Here’, but ultimately falls flat with ‘Return Of The Son Of Monster Magnet’, a failed experiment involving a bunch of hipsters, some LSD and a room full of percussion, possibly the most tedious track in the entire Zappa catalogue.

Era-fetishists may like to start with Freak Out, most everyone else should note its existence and jump straight to the superior sequel Absolutely Free (1967). Much later the Mothers’ original lead singer Ray Collins would comment of his successors, “All the guys in Frank’s band seem seem to do what they think The Mothers of Invention are supposed to do. They all try to act zany.” He’s right, some of the later bands worked brilliantly within the established confines, but none had the sense of gleeful anarchy, of defining form. Of purpose. They were all trying to ape Absolutely Free, the riotous sound of an creative revolution in full swing, the perfect balance between idealism and incredulity. Or, to be slightly less romantic, a point where The Mothers were comfortable enough to start dicking about in the studio, holding back the giggles as they took the piss out of straight society, improvising lyrics about cheesy prunes through moonbeams in June. This version is as near to perfect as makes no difference, a fresh master free of echo, revealing every glorious nuance of the original.

We’re Only In It For The Money (1968) has a similar clarity and may technically be a better album, if you’re the type who likes to quantify these things. By this point Zappa had more resources at his disposal, a larger band, more money for equipment and studio time, more experience directing the whole operation, all the ingredients necessary to make a grand statement. Money is an album of its time, one finds Zappa fully tuned in to prevailing trends. If it were funny it might mark Zappa’s peak as a satirist. As it is there’s no such risk, its humour is bleak and undermined by an uncharacteristic aura of despondent resignation. It doesn’t help that Ray Collins temporary absence left the group without a vocalist capable of any subtlety. We’re Only In It For The Money may be a great formal achievement, a timely piece of social comment but it’s also a deeply tedious album to listen to.

Much better is Zappa’s solo debut Lumpy Gravy (1968), recorded at the same time as Money with some material in common but an entirely different experience. Though they may have pushed the boundaries, all three Mothers albums to this point were clearly rock albums. Lumpy Gravy on the other hand started as an orchestral suite but by the time of its release veered off track to incorporate twangy surf guitars, primitive tape manipulations and a bunch of hippies under a piano mumbling stoned hippy nonsense about pigs and ponies. It’s the primordial soup from which Zappa would elsewhere summon order, an exhilarating ride through elements randomly assembled and welded together with brutal jump-cuts. Again, this is one of the few early albums whose previous edition sounded fine so the lack of a remaster here is no big problem.

Unlike Cruising With Ruben And The Jets (1968) which is presented here in its controversial 1987 mix. As with Freak Out it’s difficult for me to care because I always figured Ruben was a worthless exercise in nostalgia. Zappa’s original sleevenotes admit as much, minus the value judgement, calling it "just a bunch of old men… sitting around the studio, mumbling about the good old days". Except where the original had been a bunch of tired twenty-something geriatrics reminiscing over the doo-wop pop of their youth for thirteen tracks of bittersweet whine, this version is one 40-year-old bloke directing a bunch of twenty-something kids in a romanticised pastiche of the same. More Shakin’ Stevens than Sha Na Na, more Happy Days than American Graffiti.

In some ways Ruben represented a fond farewell to such sounds. That’s not entirely accurate, of course, but it’s certainly true that Zappa would never again look back at such length or with such awed reverence. From this point on retro glances would be constructive, substantial, as with the astonishingly beautiful vignettes which peppered the original Mothers final release as an active band, the double set Uncle Meat (1969). Recorded concurrently with Ruben, songs such as ‘Cruising For Burgers’ and ‘Dog Breath’ express the full range of teenage joys and frustrations with a rare mix of honesty and dignity.

But there’s so much more to Uncle Meat. It’s the point where Zappa finally managed to fuse the various elements from Lumpy Gravy into an ordered, accessible whole whilst reaching even further for source material. Free jazz is all over Uncle Meat, but also notable is a debut for the piquant yet distinctively musty ambience of material recorded live on stage. It’s the first adequate showcase for the expanded Mothers lineup, most of whom covered a range of instruments to the point where a small orchestra could be overdubbed into existence for the airless mechanical perfection of ‘Project X’ and ‘The Dog Breath Variations’. It’s not all amazing, some of the documentary material is a bit much, but again that’s only one perspective. It’d be easy enough to argue that clips such as ‘Our Bizarre Relationship’ are the most avant-garde inclusions here, anticipating by three decades the obscenity of modern celebrity in a networked age. It may even be true, personally I’ve no patience for hearing sixty seconds of Zappa’s old flatmate reminiscing about the time he had two girls in one night. Worse, this is another 80s update with forty-odd extra minutes of such gibberish.

Here I have to admit that I’ve never actually heard the original vinyl of Uncle Meat so beyond the obviously superfluous ‘bonus’ tracks I can’t compare. This version is decent enough, there’s no fluctuating treble or any of such nonsense, but given how much better the new versions of Burnt Weeny Sandwich (1969) and Weasels Ripped My Flesh sound I can’t help wonder what I’m missing. Until I heard the new Weasels I’d started to wonder if it was one of those records I’d worn out through over-exposure. And, yeah, maybe there is an element of that, it’s not an album I’ll play too often cos if needs be I can summon it up in my head, no electricity required. But I’m glad they got it right this time, glad it finally sounds again more like the version I imagine, pleased it’s more a resurrection than a remaster.

Weasels is special because it’s the sound of the original Mothers really letting go. This is the album Zappa detractors such as Penman would claim doesn’t exist, a collage of mostly on-stage moments where the band truly ‘plunge into the world of the Other’. Sure, there are self-conscious, precocious attempts to let us know just how clever they are, but why should that be a problem? If anything it’s charming, especially the moment in ‘Toads Of The Short Forest’ where Zappa lectures an audience on tempo, concluding with "the tambourine playing in 3/4, and the alto sax is blowing its nose", is delivered with a playful warmth, driven by the kind of passion that makes virtuosity something to admire even for those like me who aren’t much bothered about time signatures. You can hear this is the sound of people playing beyond the theoretical limits of their abilities, marvel at the fireworks without understanding the chemistry behind the explosions.

Despite being mostly, approximately, jazz of some description, Weasels is also notable for its breadth. ‘My Guitar Wants To Kill Your Mama’ is hard rock at its most concise, ‘Directly From My Heart To You’ is heavy blues with electric violin, the title track is two minutes of white noise, and ‘Oh No’ revises an orchestral theme from Lumpy Gravy adding a Beatles-baiting lyric more vicious and cutting than anything on We’re Only In It For The Money. For once this eclecticism was actually something of a compromise, Weasels being intended as the second of two samplers for a twelve record box set. Burnt Weeny Sandwich was the first sampler, an excellent album in its own right but one which can only suffer in comparison with Weasels. Not that they’re entirely similar, Weeny is the evil twin. Where Weasels takes ugly abstraction and makes it beautiful Weeny is a series of gorgeously poised themes — almost respectable — wantonly vandalised by garish discordance, bad vibrations. I’ll always struggle with the lifeless doo-wop covers that bookend Weeny but elsewhere more of a balance is struck, with the characteristically propulsive ‘Little House I Used To Live In’ and the uncharacteristically delicate shanty ‘Aybe Sea’ deserving special mention.

To some, everything else is postlude. Zappa sacked the band, claiming he couldn’t afford to keep paying them a retainer. He recorded the solo Hot Rats (1969) with a bunch of crack session musicians including late period Mother Ian Underwood, and featuring a guest appearance from his old friend Captain Beefheart. At the time it may have been seen as cutting edge jazz-rock, it may more accurately have been seen as hard rock with lots of long guitar solos. In either case it’s enjoyable enough, civilised light refreshment after the intensity of late-period Mothers. ‘Peaches In Regalia’ is musical helium, impossible to absorb without feeling uplifted. Hot Rats is another album appearing here in its fully restored glory for the first time on CD.

Next, needing a group to play shows, he put together a new band he called ‘The Mothers’ despite retaining only himself and Underwood from the old line-up. Fronting the new band were Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, on exile from pop group The Turtles appearing pseudonymously as Flo And Eddie, spouting aimless obscenity, revelling in the egotistical exploitative bullshit of life on the road over competent, occasionally inspired, jazz-rock. So begins the era Ray Collins referred to: the zany years.

To be fair, it’s an era that would eventually produce some of Zappa’s finest work, but unfortunately that’s beyond the scope of this batch of re-issues. Instead, for now we end with three albums that see Zappa in steady decline. Chunga’s Revenge is by far the best, if only for the majestic ‘Twenty Small Cigars’ and the lascivious ‘Would You Go All The Way’. Filmore East, June 1971 has a few engaging instrumental fragments and a whole heap of tedious drivel, but is relatively coherent next to the inane nonsense of ‘Billy The Mountain’ on Just Another Band From L.A. (1972). Is it a vicious dig at his former bandmates and their money woes? Is it another satire of conservative America, the military in particular? It’s hard to tell. At nearly twenty-five minutes of yadda yadda yadda with not a memorable tune or notable inflection in earshot I tend to tune out about half-way through. You can’t fault his ambition, but a few moments on Absolutely Free aside Zappa did not have any notable gift for musical theatre. All three of the Flo And Eddie albums sound as spiffy here as they ever will, but Chunga’s excepted that’s not much of a boast.

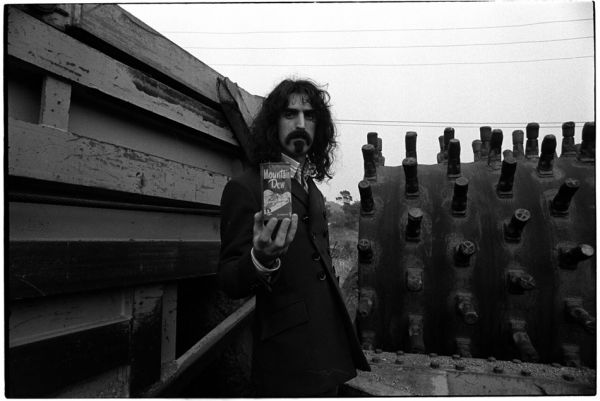

So. Not a great place to end up, especially for an apologist, let’s peddle back instead. Nobody’s perfect, demonstrating that shamelessness was one of Zappa’s many strengths. But it’s easy to ignore the weak ones, cue up Uncle Meat or Hot Rats and focus instead on those qualities that are worth celebrating. Gleeful iconoclasm. Voracious stylistic promiscuity, a pitifully low boredom threshold. And most importantly a relentless, joyous energy. Zappa, the crusty old cynic denying the existence of love even on his first album at the grand old age of 26, clearly loved music with every ounce of his being. He loved it passionately, with a magnificent intensity that illuminates most every second of those fifty-six albums, even the crap ones. It’s his defining quality, the reason why the best of his work remains powerful today.