The early 1980s was a beautiful time. Before the internet there was no easy access to reviews and technical specifications via a handset while browsing shop shelves, and the mind-bogglingly massive e-marketplace didn’t exist either. Television had barely broken out onto a fourth channel. The Sinclair QL was the state of the art in home computing. Jet Set Willy was replacing the Raleigh Strika as the must-have accessory for your Christmas list. VHS was winning the home video format war over the more compact Betamax, with video stores appearing on every high street. They, and the newly established distributors like Palace who supplied them, formed a booming business phenomenon that for a time confounded any efforts at formal regulation. Overnight petrol stations were stocking now familiar chunky plastic boxes sporting all manner of imagery, often disturbing and suggestive, but always intriguing.

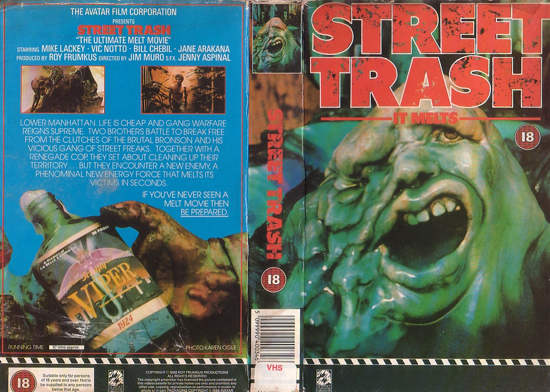

The marketing of the new media was underway and video cassettes, like records before them, relied almost entirely upon their covers to shill their wares to hungry consumers. Although modern, tech-savvy youngsters no doubt struggle to imagine how people managed to entertain themselves with such a primitive array of options, it is easy for those who experienced that mode of selection to pity the more recent, spoon-fed generations. Video stores, like record shops, were cornucopian treasure troves. Horror, fantasy and science fiction features were, aptly, the heavy metal albums of the film world. Every video store displayed its wares face outwards, ensuring that the horror section was a bewildering wall of colour and fine detail consisting of yawning skulls, bloody knives, pop-eyed cannibals and gas-masked killers.

Above, below or across these images in futuristic or gothic fonts were bold, titillatingly promising titles such as The Arousers, Body Parts, Flesh Eating Mothers, Inseminoid and Twitch Of The Death Nerve. In the UK this flood of lurid material enraged many and the well-documented ‘video nasty’ phenomenon dominated newspapers throughout 1982 and ’83, consigning numerous titles to a life of obscurity until the DVD era of the late ’90s and onwards. Since then the vast majority of the banned titles have been re-evaluated and released uncut, much to the disappointment of gorehounds whose fantastic imaginations had conjured up much more interesting possibilities based upon those tantalising old video case covers, many of which bore no resemblance whatsoever to the actual content of the films.

The Video Recordings Act of 1984 brought regulation to the marketplace, successfully ensuring that hysterical councils were less likely to ban movies on the strength of a cover and also that innocent video store owners could no longer be gaoled for offences under the Obscene Publications Act after renting or selling copies of boring rubbish like House On Straw Hill. It also ensured that films distributed on video cassette would be subject to the same controls, and an even greater degree of brutal editing, as mainstream cinema. Fortunately the VRA did not end the trend of marketing videotapes with brilliantly lurid covers enclosing exploitative, imaginative, low-budget schlock that in the USA could be viewed uncut and as intended, in its natural home, the fleapit grindhouse cinemas of New York’s 42nd Street.

Perhaps the most gratifying example of the marriage between video cover and content is Jim Muro and Roy Frumkes’s melting tramp movie Street Trash, which came out in 1987. Had this been made pre-1984 VRA there is no doubt that it would have fallen foul of the humourless censorship movement and been condemned to the banned list. As it is the BBFC-approved video release was edited, mostly to remove several shots of a tramp’s severed penis as it becomes the object of a light-hearted kick about by his fellow hobos.

Street Trash is a rare example of the art in that it is exceptionally well-made. Most pictures of this ilk tend to be less than impressive from a cinematographic perspective, but here the image is bright and crisp. Hence the graffiti- and litter-adorned New York slum locations, plus all the exploding tramps therein, are rendered in exquisite detail. This is unsurprising considering that cinematographer David Sperling was a genre veteran and first-time director Jim Muro (later credited as J Michael Muro) would himself go on to become one of the most highly regarded cameramen and cinematographers in Hollywood. For many years he was James Cameron’s first choice Steadicam operator.

Scriptwriter Roy Frumkes, better known for his George A Romero profile Document Of The Dead, may not have demonstrated an acute grasp of narrative when he expanded Muro’s original ten-minute short to a 100-minute feature but he did, by his own admission, set out to be as offensive and tasteless as possible. In these respects Frumkes succeeded admirably. He also injected a hearty dose of gross-out humour into proceedings, that might not have worked were it not for Muro’s impeccable eye for detail. The vibrant and improbably coloured make-up and gore work made the entire experience so vivid, while committed cast performances combined with all of the above to ensure an explicit ridiculousness.

The plot revolves around a consignment of out-of-date hooch and its devastating effects upon the daily lives of a dysfunctional community of hobos living in and around a New York junkyard brutally ruled by a violent, PTSD-afflicted Vietnam veteran with a penchant for ultra-violence. Of course, the ramifications of the toxic beverage go way beyond its impact upon coping mechanisms, contributing to emotional instability and causing long-term liver damage. Fortunately the results for the audience are not ill-smelling, overbearing and depressing but deliriously entertaining, gooey and hilarious.

This picture and its close contemporaries are undergoing something of a renaissance, with Street Trash receiving a fine 2010 DVD release courtesy of Arrow Video. Frank Henenlotter’s Basket Case trilogy is to emerge on Blu-ray for the first time thanks to Second Sight, with Stuart Gordon and Brian Yuzna’s Re-Animator and From Beyond set to follow. For those who prefer the late night grindhouse experience, Street Trash can be enjoyed in its glorious, colourful, penis-volleying entirety this weekend at the Prince Charles Cinema in London.