"In this disturbing country, so far as I have become acquainted with it already, it is possible more easily to discard the inessential and accept the infinite. You will be burnt up, most likely, you will have the flesh torn from your bones, you will be tortured probably in many horrible and primitive ways, but you will realise that genius of which you sometimes suspect you are possessed, and of which you will not tell me you are afraid."

Johann Ulrich Voss, Voss

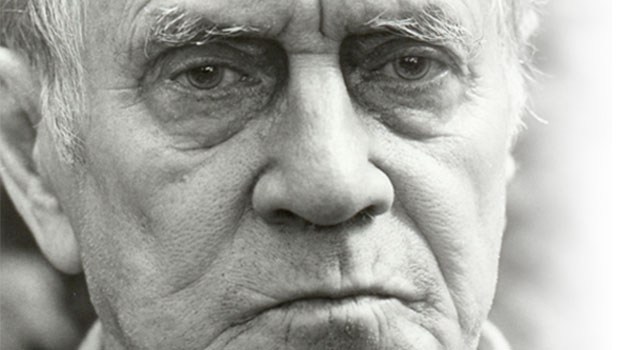

The game of positioning great writers in hierarchies or league tables is never a very graceful thing. Nevertheless, a judgement by juggernaut of Australian criticism Peter Craven gives a clue as to exactly how serious Patrick White’s stature in certain circles is. In the accompanying guide to an exhibition of White’s letters, notebooks, photographs and other personal ephemera at the State Library of NSW, he attaches to White an importance of a degree that many people – both inside and outside Australia – would find unimaginable. White, he says, is a rung down from the seismic trio of Joyce, Lawrence and Proust, yet is deserving of a place in what he calls the "next division": Beckett, Nabokov and Waugh.

Perhaps, though, both stylistically and in terms of the daunting proposition he offers to casual readers and students alike, it is truer that White has more in common with Faulkner. The author and his writing represent a divisive and ongoing problem, whether you are considering him as part of the 20th century canon or, indeed, as an Australian. Few of his countrymen have ever been as demanding or scathing of the moral outlook and intellectual capabilities of the nation as White.

2012 is the centenary of White’s birth, heralded by TV programmes, lectures and exhibitions in Sydney, Canberra and Mount Wilson, the release of an unfinished ‘lost’ novel and a new edition of his first, Happy Valley. It is arguably Patrick White’s most important year since his death in 1990, in which time he has gradually faded out of Australia’s cultural milieu.

His novels are obtuse, uncompromising and nearly always staggering – driven by an unflinching confrontation with hate, lust, love and art; his language always curiously out of sync with any literary modes that emerged during his career – which ran from the 1930s to 1980s – most of which time he was based in or around Sydney, getting angry, losing friends and berating two of his life-long hates: sports and journalism.

Seeking ideas for this piece I ventured to the library at Sydney University and unearthed such bleak-sounding books as Patrick White: A Vision of Man and God and The Future of Patrick White: Eschatology, Apocalypse and 20th Century Fiction. Clearly, despite his wavering appeal he remains a source of much earnest academic handwringing and analysis of things like his status as ‘seer’. I, however, have a different relationship with him.

I spent the first 12 years of my life in the rural Hawkesbury region that sits between the outer fringes of Sydney and the Blue Mountains – a beautiful but often punishing environment in which to be a child and one where, if you’ll forgive the musing, the colours, light and sheer atmosphere leave a profound impression; even if the people were and remain rabidly right-wing and in thrall to developers, turf farms and 4x4s. Then, I was shifted to the UK where I stayed through adolescence and early adulthood, moving afterward for a year to Zurich, Switzerland. It was then that the pull to return to Australia became more insistent than ever: in the early months of 2010 I was faced with a decision on whether to do so, or return to a Britain where Cameron was soon to become prime minister and where the media landscape, from an employment perspective, had become a devastating quagmire that held no opportunity nor desire. Yet, in Australia too, I had limited family and friends, no contacts or professional leads and the prospect of a city (Sydney) fast becoming among the most expensive in the world.

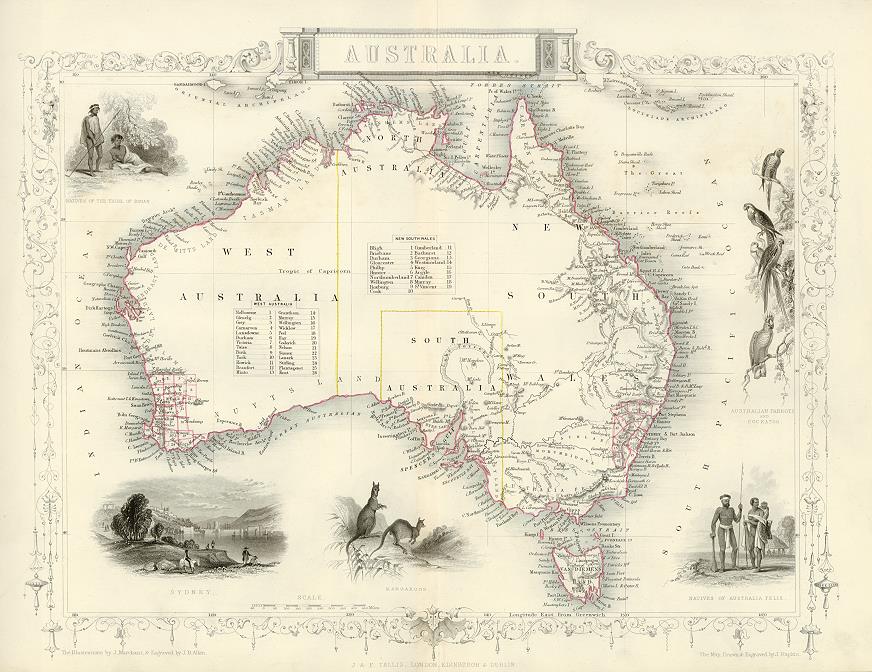

At this point I read Voss (1957) and The Tree Of Man (1955), one after the other. The former is ostensibly a story of a German explorer’s monomaniacal intent to conquer the Australian landscape and his spiritual, almost telepathic relationship across the continent with a well-to-do but existentially unsettled love interest in Sydney. (It is loosely based on the expeditions of both Ludwig Leichhardt and Edward John Eyre.) White’s descriptions of Sydney, northern NSW and the Darling Downs terrain are not beautiful; the combination of the landscape’s indifference and the wrath men heap upon themselves when faced with their physical and metaphysical ineptitude before it, make Voss at times an uncomfortable read. White’s conveyance of Antipodean space has a resonance that can be found in more modern writers such as Kate Grenville and poet Robert Adamson, as well as – and I’m deadly serious here – the lyrics of Neil Finn (particularly on the Crowded House albums Temple of Low Men and Together Alone).

Later in life, White became friends with influential Australian painters Sidney Nolan and Brett Whiteley (before falling out with both, and quite spectacularly with former; other friends he eventually brutally discarded include Barry Humphries, the author Geoffrey Dutton and the director John Tasker), and once explained that Voss was meant to be suggestive of a Blake painting: distressing and hellish. It is an abstract, distinctly painterly tale of psyche sinking into environment, and it was a piece of the Australian experience that instigated some odd sense of recollection in me. Indeed, White’s own reasoning for returning to Australia himself to write was, he said, the "stimulus of time remembered".

But it was not his depiction of that land which had me decide to move ‘home’ – it was the hold the country seemed to have on White’s characters. In beautifully simple terms (at least for White), Laura Trevelyan picks up on how, in this place, "the air will tell us" of both the land and of one’s self. While in a rather milder assertion than that which opened this article, Voss himself: "I am compelled into this country" of which he takes ownership "by his right of vision". Even today in Australia amid mining, gluttonous real estate and a hilariously childish political climate, that is a tantalising idea.

Of course, the grip of Australia was on White himself, who when interviewed upon winning the 1973 Nobel said Sydney was "in his blood", even if his heart was in London. In a century where Australia’s artists and musicians fled the primitive colony for Europe and the US, White returned to Australia in 1947 and stayed. "I shall continue to live here," he said in 1973, "as I feel the need to fight certain elements."

The Tree Of Man was a more conventional novel of pioneering, settlement, family and normality, while others such as The Eye of the Storm (made into a film last year), The Aunt’s Story and Riders In The Chariot are more societal portraits of the vanities of relationships.

Arguably his most extraordinary achievement must be The Vivisector (1970) – the story of an artist’s life as he uses and then discards the people in his changing inner circle for the sake of his craft. If Stan Parker’s death in The Tree of Man stands as one of the great deaths of literature, as biographer David Marr has stated, then the electric scene in The Vivisector of Hurtle Duffield feverishly painting with his own faeces in a shack amid sandstone and bush stands is even more incredible.

By the time of his death, White had published 12 novels, had enjoyed much success in the theatre and was in the public eye as a campaigner against uranium mining. He was also a misanthropic old grump with a loathing for the vacuity of modern Australia – disdaining advertising, television and development in equal measure. He never came across with softness or amiability and it is this, as well as the perceived formidableness of his work, that makes him either unknown or written off by the majority of Australians.

It has been a long time since White was a common inclusion on any university curriculum; but more serious is his lack of influence across wider culture. Worryingly, a high school English teacher friend told me she had never heard of him, while another, a literature post-grad with theses on Australian literature behind him and a book critic, has never read White: "Certainly no one’s been particularly clamouring to keep interest in him alive, and I wasn’t even aware of him until university. I’m still not tremendously attracted; I think the idiosyncrasies of his style are as likely to repel as they are to dazzle and for many that’s a hard thing to overcome."

The other telling thing is that at the many talks and lectures the State Library have put on to mark White’s birth, the average age of attendees must be somewhere between 60 and 70. And, if several overheard conversations are anything to go by, some of them appear to be interested because they remember him as a curious public figure in the 80s rather than an author.

It is not just from the general population that White is subjected to ambivalence. He has had his fair share of critical ire down the years, none more memorable than the poet AD Hope’s put-down of The Tree Of Man: "pretentious and illiterate verbal sludge". But easily the stupidest (or most ignorant) thing ever to be said about White was that he was ‘un-Australian’ – even if some of the things that made him nauseous about the place were (and remain) ingrained parts of Australian life. But, living in the country for his last 43 years and the fact the majority of his novels are set here, suggests that like many literary dissenters censorious of their homeland, his criticism is motivated only by his belief in the nation’s immense potential and his frustration at what he called "the great Australian emptiness".

White never missed an opportunity to complain about Australia’s obsession with sport and, more particularly, with winning. One of his finest quotes makes reference to "the soporific thud of the cricket ball [and] the gladiatorial displays by steak-fed footballers" clarified and encapsulated by the phrase "Sport could sink us…" Many of his books include witheringly satirical depictions of the rich (usually women), a section of society he knew well thanks to his inherited wealth. This gave way to a more direct hatred of the global new breed of rich in the 80s who would declare themselves with the accumulation of products and cars, measure themselves by European or American standards and preside over the neglect of compassion and sensitivity.

In some ways, each of White’s books is an exhortation for each Australian to explore his or her inner space and rise above the complacency and philistinism he saw so acutely: their morality, their motivations, their intentions and their context. White seemed to relinquish the travel bug when he returned to Australia – from this point on, a fascination with all those things, in this setting, certainly seemed to occupy him.

A few weekends ago I went back to the Hawkesbury, to hills and valleys of grotesquely long bungalows in the unique Australian style and pubs full of swaggering bikies. On the train back to the city, a slightly overweight young man got on, dressed mainly in black, listening to music, only to be immediately set upon by three younger denizens who shouted at him to "move you dumb fuckface" and that they "hate goth scum", before sticking the dog they had with them in his face and goading it to attack. The following day at Town Hall station in the city my train was delayed for 10 minutes because someone had spat in the face of the guard.

The rugby league season has just finished, with many matches played at a stadium a stone’s throw from the house in Centennial Park that White shared with his partner, Manoly Lascaris. The stadium sits on ground White vigorously campaigned to protect from becoming such a mecca of sport.

These things are certainly not unique to Australia, but they are perhaps symptoms of the fact Australia has not budged an inch to White’s ideal. His rallying cries to improve cultural life may be unheard today, but his work remains a trove of quite mystical allure. A hazy, at times warped manifesto for the country he left behind.

Much of Patrick White’s bibliography has been reissued by Random House Australia