On its initial release, in the same year that Reservoir Dogs drew similar fire, C’est arrivé près de chez vous (It Happened in Your Neighbourhood) sparked debate concerning its graphically violent content. Considered controversial enough to be banned in Sweden, this no-budget Belgian mockumentary continues to repel and attract audiences in equal measure.

Winning two awards at Cannes in 1992, Man Bites Dog – as it is known by English-speaking audiences – has since been marked as one of cinema’s early critiques of reality TV, before reality TV even became a proper thing. The project was conceived by Rémy Belvaux who, on the hunt for a subject that could be made with zero funds, began collaborating with André Bonzel and Benoît Poelvoorde. Their plan was that the three of them would star in the piece’s main roles, while Poelvoorde’s family could fill in for the much of the rest.

The concept that Belvaux came up with was a simple one in theory, though complex in execution: a film crew make a documentary about a serial killer, Ben (played by Poelvoorde), as he goes about his business, murdering at random and stealing cash. They follow him everywhere as he picks out victims and takes them down, often in the most brutal fashion possible, while genially pontificating on subjects as diverse as the subconsciously oppressive colour schemes of urban architecture; the abstruse ballast-to-body ratio for sinking a corpse (depending on its age, weight and size); the importance of open communication to forge a loving relationship; and then, of course, the most effective methods of killing people.

At first, the camera crew who are as passive as an observer can be when witnessing the strangulation of an innocent woman, but soon become more complicit in the crimes. They begin helping, by either literally shining a light on the situation, or by aiding Ben heave a carpet-wrapped body over a cliff, or into a stolen car’s boot. When they run out of money, the killer steps in and begins directly funding his vanity project. Going from council estates, where he preys on old, lonely women in one of the most memorable scenes, to parties with the ‘art crowd’, and on to the suburbs, the picture apparently moves to make a comment at each level of society, then leaves the rest up to the viewer.

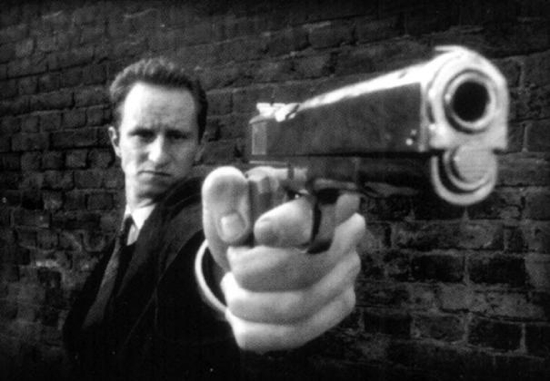

In each area of the city we’re shown smash cuts of murders, carried out predominantly with a high calibre pistol or Ben’s crazed hands: a wash of ‘kills’ that flood the brain, somewhat akin to Alex’s forced treatment in A Clockwork Orange. The intended effect seems to implicate the audience in events which, even in grainy black-and-white, somehow take on a grave, disturbing colour. Most alarmingly we laugh, albeit through gritted teeth and with question marks in our heads, at Ben’s gallows humour – as fast and as dark as the film stock that records it, invoking the swagger of Martin McDonagh’s early stage work. Both are twisted and, arguably, pointed.

Eventually things go too far for the crew. They become active in the shaping of their film’s subject to the point that, after a heavy drinking session at a local pub, the group happen upon a couple at home in the middle of an intimate moment. They interrupt that moment and, taking turns, rape the wife and taunt the on-looking husband.

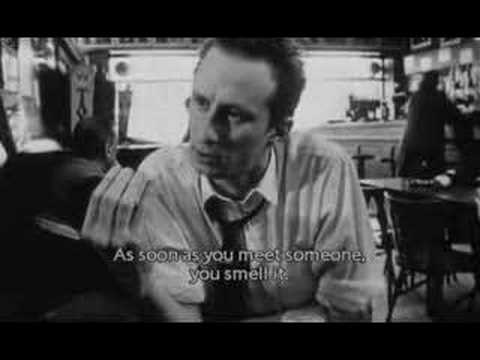

It’s no wonder that critics and audiences found, and still find, some of these images hard to stomach. Much has been made of the graphic content. In an interview for television (see below) Bonzel, perhaps in an attempt to temper some of the critical backlash, argued: "It’s a film about filmmaking, and the process of making a film… Instead of being a killer, Ben could be a door-to-door salesman… It would be the same thing." (See the Maysles brothers’ 1969 doc Salesman for a serial killer-free illustration.)

In both these interpretations, offered by filmmaker and critic alike, the movie’s main thrust is plain, blunt and without subtlety. However, Man Bites Dog is one of the stronger examples of filmmakers penning a workable concept that functions with the least amount of money. The mockumentary genre has always allowed a fair amount of latitude in this respect, particularly in terms of debut features, to make films that become ‘calling cards’ for bigger budgets. It provides flexibility: the crew are absorbed into the cast, using one handheld camera and a boom mic that become part of the action. The result is a simpler shooting schedule. The focus can rest on the subject, rather than any complication of technique. Even the discussion of budget, which was a serious problem for Belvaux and company, becomes part of the film within the film. One recent example is Wizard’s Way, a first feature by three Manchester-based novelists screened at this year’s London Independent Film Festival, which also proves such an approach to be an expedient one.

There are some weaknesses to this style in Man Bites Dog. Though heavily scripted from start to finish, it reveals that its conception was a vague one that was subsequently made workable. Starting out with an idea that only has a beginning and an end, Belvaux required a middle to be foisted in, and it shows. After the first 30 minutes the movie slows down noticeably, becoming aimless and wandering. There are several of these meandering sections, in which the trajectory seems impulsive, ambling toward making a message and then backing away. It is at its strongest when Ben plays for laughs the absurdity of the situation, rather than the murder. Pointing to the irony of the crew stuffing bodies into trunks, or digging holes in a makeshift graveyard at the bottom of a drained reservoir, perhaps better serves the filmmakers’ stated purpose than fixating on the various ways in which a head is shot off.

But the film sticks to its guns, and does not waiver from its central thesis. It’s not so much a statement about the complicity of the media, but rather the latter’s direct involvement in this escalation of violence. That said, the piece doesn’t seem particularly dogmatic: we are merely given this situation to make of it what we will. Man Bites Dog is not the sole progenitor of the form, nor does it pretend to be. An earlier example is 1968’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One and its lesser sequel Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2½ (2003), both helmed by William Greaves. These tackle the observer effect via the form of (faux) docudrama – what it was called before comedy became part of the equation – thereby making a film within a film within a film.

Frederick Wiseman also explored similar notions by reportedly spending days ‘shooting’ with no film in the camera, so that the subject could begin to ignore its presence. John Cassavetes, Robert Altman, Elaine May, Quentin Dupieux and countless others have tried similar techniques – to get at the core, or at least play with it.

Many of these exercises – though not all – were doomed by over-intellectualising their execution, and perhaps also by the inherent impossibility of an objective film document where the subjects are aware of the recording. The success of Belvaux, Bonzel and Poelvoorde’s attempt to advance these themes is certainly in question, yet their style, ambition and humour have carried Man Bites Dog through to cult status, where it will surely remain even after another 20 years.