"D for effort/ D for intent/ D for love/ D for insight" – Codeine, ‘D’

I’ve been careful in this series to never talk about what I ‘miss’. Nostalgia’s a virtually impossible stance to maintain in print these forward-blinkered days, seems ungracious, or worse reactionary. But the point of nostalgia is that it’s a yearning for that which is totally irretrievable. I don’t ‘miss’ these bands. I don’t ‘miss’ the feelings they engendered. What I miss if I’m honest, and if I forbid myself any chance of fucking moaning about the present, is quite simple. Starvation, and ignorance.

Not innocence, ignorance. Pop nostalgia’s sweet & sharp neuralgic hit for those of us who remember the 90s with fondness lies in the fact that what you really miss is not pop objects, or what they contain, it’s the launchpad into nowhere that an utter LACK of information engenders, the chance to make up your own stories rather than instantaneously be availed of the facts. And in contrast to the glorious perma-glut of 2012 wherein there is always too much to listen to, back then you were comparatively starved of music, through poverty and high standards, so those half a dozen totems that pulled on your time every year became megalithic in their dominance of your day, their sun-blotting towering presence in your life. Not saying I want that back. But at root that’s what we miss if we do look back to the 90s – perhaps the last time that demystification of music wasn’t instantaneous, and then concurrent with that music’s enjoyment.

With so much of the music you loved, you knew next to NOTHING about the bands making it, let alone any ‘scene’ it could’ve emerged from. That dead end of darkness meant your imagination became focussed on almost invisible threads, single images, single songs, the sleeve, the sound, NOTHING else. A confused, unaware place as a pop fan, whereby your own input into what you listened to grew as time went on, never receded under the glare of what was really going on, or any nuts and bolts you could tease out. It’s rare now to let yourself be that uninformed, let your imagination play tricks on what you hear, and what you hear play tricks on your imagination.

All you had to go on in 1990 with Codeine’s Frigid Stars was a shot in negative of star formations on the front, and a picture of someone lying on a bed covered in coats on the back. Some song titles. That was it. Codeine’s sound, whispers, barely heard words, slow gorgeous songs of dissonance and darkness, disencumbered from any known media we could find and put only with hugely suggestive images of its own choosing, became overwhelmingly intense, unbearable to play when actually sad, beautiful in its sadness. As far away from traditional rock & roll heat as a post-stellar universe is to the Big Bang. And swiftly, after the initial shock of how they played became something you lived with and loved within, they suggested altogether different trajectories and impulses behind American art than you’d been tutored in. They weren’t exactly a way of life. But they were a whole new way of getting used to dying.

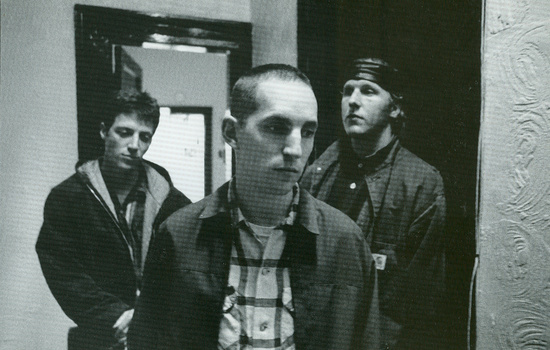

Nuyoricans Chris Brokaw (drums), Steven Immerwahr (bass) and John Engle (guitars) formed Codeine in Oberlin in the late 80s. Like other dazzling urbanites, they found in Oberlin a retreat from big-smoke pressures and confines.

Chris Brokaw: "I chose Oberlin for a few reasons. It offered an excellent general liberal arts curriculum, as well as a world class conservatory. I knew I would be studying literature, but I was happy to have the facilities and resources of the conservatory on hand. I also really wanted to be fairly isolated; I wanted to focus on academics and not have big city distractions. Oberlin was great; I met a lot of interesting people, I was introduced to a lot of culture and outlooks that were new to me. There was a ton of music happening on campus, of every stripe, because of the conservatory. There was also an excellent radio station there, and i worked there all four years; I also DJ’d at the campus disco! I liked Ohio a lot, I liked the people I met in Oberlin as well as in Youngstown and Cleveland."

Steven Immerwahr: "Oberlin is a really small school, but I was also very, very shy, so it took a while for me to meet people. Any rate, most of the Oberlin musicians I met I met through Lexi Mitchell (who went on to play in Seam), including Sooyoung Park, John McEntire, and John Engle through his brother Jeremy who was at Oberlin. She also had unerring taste in music. And she had the first Jesus & Mary Chain single the same month it came out!"

One thing that also seems to come from Oberlin musicians, is this idea that a band, and the relationship between individuals that that implies, shouldn’t be a straitjacket or necessarily lead to a ‘gang’ mentality – rather a band is a moment when a few like-minds come together, always with the possibility that it could fly apart. Would you say that you started Codeine with an idea of your future, or with a total career-careless focus on the music?

CB: "I don’t think any of us thought of music as a career. I’m not sure any of us had much sense of any kind of career. But Steve said to me very early in the life of Codeine, ‘I don’t see this band lasting more than a year and a half or two years.’ Besides the fact that none of us were looking particularly far down the road, I think we approached the music as a project, and as an end in itself. it wasn’t about a career, it was about realizing these songs."

SI: "Something I think was consistent about many indie rock bands then was that playing in a band was absolutely not about a career in rock. I certainly wasn’t interested in being a rock musician as a career or vocation. Chances seemed slim, and wanting that seemed stupid anyways. Among other things, we turned down a really lucrative publishing deal because having our songs in commercials was a very distressing idea at the time. The music biz lawyer we talked to about it was also incredulous when I suggested I might not want to play music professionally for the rest of my life. ‘But what would you do?’ she asked. I just knew that I wanted to do this music. We did it and then I was done."

Were you all based in New York in the early Codeine days, or have I got that calamitously wrong?

SI: "Initially, yeah. I met John Engle in January 1987 at his parents’ place on West 100th and Riverside Drive. I knew John’s younger brother, Jeremy, from Oberlin, and was couch-surfing for a month or so. As soon as I met him I knew that we were going to be in a band together, but I’d just finished school and was completely broke and was moving to Swarthmore, PA, to be a nanny for my cousins who were 4 and 6 at the time. A great job for someone just out of school. Nothing like taking care of kids for a few months to get you focused on doing other things!

"Basically, I knew we were going to be in a band together at the start of 1987, but aside from recording an eight minute cover of ‘Without You’, we didn’t play live together until the first Codeine show in 1989. Chris came into the picture via Sooyoung. Chris was my class at school, but much much cooler and a total rocker babe, so I doubt I ever spoke to him at Oberlin. So Sooyoung was to blame for that too, as I think he’d passed a tape of the recording with Peter Pollack and other 4-tracks along to Chris, and suggested him to play drums for the first Codeine show at the Muddle East in Boston. Sooyoung did so much to help me and Codeine along, it’s really amazing."

CB: "John and Steve were both in New York, I was in Boston. There was a brief period, December 1989 to April 1990, where I was also living in New York, but for the rest of the time I was in the band I was always in Boston. Steve and I had met at Oberlin and knew each other just a little. Sooyoung Park sent me some of Steve’s music around 1988 or early 1989, which I really liked – I contacted Steve and we met up in New York and decided to work together on it."

"Meanwhile, Steve had moved to NYC after Oberlin, and become friends with John, through John’s brother Jeremy who had been at Oberlin [as immortalized on fellow Oberlin-alumni Liz Phair’s ‘Jeremy Engle’]. Originally we considered me just playing 2nd guitar, and having our friend Mike McMackin be the drummer, but we decided it would be simpler and more efficient to have it be just the three of us."

When the songs on Frigid Stars were written, did that uniquely Codeine-ish arrangement/treatment come naturally, or was it a conscious decision to make it so full of space and suggestion? What, if there was one, was the ‘process’ of Codeine? A democracy? An attempt to play Stephen’s songs as faithfully as possible?

SI: "Codeine’s becoming was not by committee, it was by force of will. When I described the band I had in mind, John said it sounded interesting but who would I get to play guitar for it? (Answer: you, you dummy.) So I really had an idea of what I wanted it to sound and feel like, in some ways something sonically and emotionally very restrictive, and in opposition to the epic and histrionic. But working out what that actually was took John and Chris. And Mike McMackin too: recording Frigid Stars LP in his basement was how we got to it. (Unfortunately, we never had such an easy time recording ever again. In fact, we had pretty dismal luck with recording from then on.) We knew we were different, and somewhat more conceptual than other bands. We didn’t work as steadily, either, because of Chris living in Boston and among other things we all thought it would be a lot easier to play slow! But it’s not."

CB: "I’m delighted, Neil, that you found it so natural as a listener – many people at the time found it quite weird. We didn’t think it was. Obviously it was very specific, and really precise, and those were active decisions – we didn’t just roll out of bed one morning and start playing Codeine music. Although after a while that style of playing became very natural, and ultimately instinctive, for me at least. The slowness was the most obvious aspect of the band, though maybe not the most interesting or distinctive. Steve’s songwriting, and style, was very idiosyncratic; I think the three of us just tried to follow that and craft it as effectively as possible. It was very detail-oriented and we discussed the details endlessly."

How did you prise ‘New Year’s’ from Sooyoung?

CB: "We were friends with Sooyoung & Lexi & Mac, Seam and Codeine were tight. Steve and Sooyoung had a really good relationship as friends and as musicians and as songwriters."

SI: "John had a Fostex X-15 4-track cassette recorder, on which he recorded various covers and stuff with his brother and friends. And this was the thing, the magic studio. And some cheap mics and a tiny guitar amp with a "Tube Stack" switch on it that made it more distorted. So basically, he had an entire recording studio. Every Codeine song on the first record and multiple songs on other records were first written and recorded on that machine. When Sooyoung was in town, he’d come over to record on it. For instance, he played bass on the first sketch of ‘Broken-Hearted Wine’ when John and I were living together (a brief, tumultuous period). Lexi [later of Seam] also lived in New York, and did songs on it, and she and Sooyoung recorded ‘New Year’s’ about a year before Seam started and almost two years before it was on Seam’s Headsparks. It’s a weird fit on Frigid Stars, more pop and more twee than anything else."

How was Frigid Stars recorded? How come I keep bumping into the name of Mike McMackin – what was so good about him that made Codeine and others (Bitch Magnet/Come) use him so often?

CB: "Mike McMackin was another Oberlin guy. He did a lot of recording, and in fact Steve and Mike worked together at a recording studio in NYC for a while after Oberlin. I think he understood what we were trying to do and really helped us with it. We recorded Frigid Stars in his basement in Brooklyn – he set up an 8-track recorder and mics etc in the basement, had the wires running upstairs to the mixing desk… he’d never done it before, it was all kind of an experiment. None of us had made a record before, we were up for anything. Also, we didn’t really have an audience or anyone with any expectations about it – the first four songs on Frigid Stars (‘D’, ‘Gravel Bed’, ‘Pickup Song’, and ‘New Years’) were a demo for Glitterhouse records, who were interested in the band. They liked them, said we could release them as two 7"s or record another four songs and make it an album, which we chose to do; we went back to Mike’s basement and recorded ‘2nd Chance’, ‘Cave-In’, ‘Cigarette Machine’ and ‘Old Things’ as side two. Making the record was fun, interesting, pretty easy."

SI: "Recording Frigid Stars was cool: we rented a bunch of mic stands and cables and a few mics, and ran a big snake out the basement window and back in through the front window of Mike’s apartment on the first floor. I played through someone’s little Peavy TKO65, John played through Mike’s Fender Twin, and we did four songs in two days in May and then again in July. July was a little more difficult: we were running a dehumidifier between takes to make being in the basement a little easier. We took it very seriously, but it was also more relaxed and much less sterile than the various recording studios we went to later.

"Although he was in my year, I didn’t know Mike McMackin at Oberlin, I only met him after in NYC when he was already working as a recording engineer. He was hooked up with someone who suddenly had the money to build and run a really big recording studio, and I was able to come to NYC because I work on the interior construction and then was an assistant engineer once the place opened. And I got to use down-time for recording, including the proto-Codeine songs ‘Castle’ and ‘Three Angels’ that John and I played with Peter Pollack on drums. He was a solid guy, and had undeniably great ears. But recording bands is tough and I think there were other engineering challenges that interested him more: he was always involved in various broadcast technology."

Were you all seeing Codeine as something that would last beyond that first record? How was the record received? How was the record misunderstood – if it was?

SI: "When I did sound for Bitch Magnet’s first European tour, the deal was this: when asked what the happening new and unsigned American bands were, they were to mention Codeine. And it totally worked: Glitterhouse read our name in Howl magazine, and sent a fax to Bitch Magnet to find out if Codeine were still unsigned. We sent Glitterhouse a tape with the songs that John and I had recorded with Peter Pollack on drums, and they offered us $500 for ‘Castle’ to be on a compilation they were putting out. We used that to pay for equipment rental and Mike McMackin’s fee for recording the four songs that ended up being the first side of Frigid Stars LP in his basement in Brooklyn. Glitterhouse liked those and offered to give us more money for a full record. So we rented gear again, went back to Brooklyn and finished the record. We had no idea what we were doing, and whatever we thought we knew then was probably wrong. We weren’t really worried about it. We thought we’d play some shows and didn’t think about whether there was going to be anything more to it."

CB: "Glitterhouse had heard the song ‘Pea’, which Steve had sung on a Bitch Magnet 12" called ‘Valmead’. This is kind of an example of how tight and linked Steve and Sooyoung were at the time… so we signed to Glitterhouse first, just for Europe; they suggested we try Sub Pop, we sent them the tape, they liked it, they signed us. That was it. Pretty easy, in hindsight. I’ll repeat: I don’t think any of us had any notion of a career in music. We wanted to make the record, and play some shows, but, anything like a ‘career’ was pretty abstract, to me, anyway, very hard to imagine. I don’t think it really crossed my mind – the record was received pretty well. It got a lot of attention. At least part of that was that it was the first record on Sub Pop that didn’t ‘sound like a Sub Pop record’. Some people really loved the record, some people thought it was bizarre. I think in general it was thought of as… remarkable."

The point was never how slow Codeine played. It’s that after a while you didn’t notice, and seemingly nor did they. They never sounded like they were going to change what they did for anyone, or that their glacial step and structure were set up for their own undoing by noise or volume (the slow/quiet – slow/loud trick that got hardened into a math-rock orthodoxy by most of their antecedents). Codeine were gonna stay there, drifting with the pace of a tectonic plate, alongside your own pulse, in no hurry.

Unlike the more self-consciously ‘exploratory’ bands who came in their wake, Codeine (although they had the right to claim a startling originality) utterly rejected such ‘pioneer’ status, were less about experiment or elaboration or discovery, way more about the disciplined uncovering of emotion and that emotion’s clearest most concise expression. And in the way they found to do this, they were unique, genuinely NO antecedents to that sound. The only true progenitors to what Codeine did are not musical but cinematic, artistic, literary – the lingering gaze and compassion of an Ozu, the space and shadows of 19th Century Luminism, the action-free subtlety and sudden significance of Raymond Carver. But bands? No-one before Codeine sounded like Codeine. Tons of bands after ripped them off, only Low and Bedhead & Idaho (check out ‘Year After Year’) doing so with any intrigue or reward.

‘Seminal’ is a horribly overused word in rock thought, implying a desire to lay down legacy, spelunk something immortal, usually with a very masculine sense of penetration and putsch. What Codeine suggested wasn’t a carving out of the unknown but a new architecture of the heart using new materials, feedback not used as a destabiliser but as a moment of radiant truth, rhythms like a dripping tap in a lonely kitchen, rock absolutely shorn of romance but still deeply involved in and about relationships between humans. So it was music that gave consolation, but not by mapping out possible redemptions or enacting revenge – just by simply mirroring moments that were unmistakeable to anyone who had a heart, anyone who’d ever had that heart broken.

Steven, I need to ask about the lyrics to Frigid Stars. They mainly seemed concerned with bereavement, of both life and love. They seem to be lyrics about a relationship, a pretty fucked up relationship, now ended. Am I barking up the wrong tree trying to read meaning into Codeine’s words? Were lyrics an afterthought to the music, about finding phrases that suited? Or were they pulled from sundry jottings, recollections of snatches of conversation? Crucially you made a decision not to be a purely instrumental band and write songs with words – did you increasingly find the need to find words a limitation or was it important to you that your songs did carry meanings, no matter how ambiguous?

SI: "Some songs were inspired by a lingering post-breakup state, one that I gradually realized had less and less to do with the specific breakup and more to do with my own orientation to others. All the songs were written on guitar with at least some of the words already written. It was almost impossible for me to write something without some words to invoke the necessary intensity of feeling for writing. Which suggests now that an instrumental approach wouldn’t have worked for Codeine, although that seemed really attractive at some points then.

"I wish I’d known what made me write songs then. I was writing constantly, which was great. But things became much more difficult, and eventually impossible, which was the end of the band. Both close listening to the masters for the reissue and rehearsals have made me spend time with the lyrics again. I’m not totally happy with them, especially written out: too much rhyming, and not really great writing. It’s not really poetry, or even very many words. Any rate, the lyrics came from all over, but I kept a journal for pretty much all of college and into the start of my 30s, so things got worked out in there if they weren’t written with guitar in hand. Actually, I just threw all my journals away three months ago. They were a good practice to maintain, but not rewarding to look through."

Were you, after Frigid Stars a functioning touring band? Were you geographically together or displaced? How easy is it to convene Codeine in 1989/1990 post-graduation?

CB: "No, we weren’t a touring band, we didn’t know anything, we were very green. We did one tour in Europe with Bastro in October 1991, for about a month, which was great, really fun & interesting. Mostly we just played on the East Coast, primarily New York and Boston; New Jersey; Connecticut; North Carolina and Virginia one time. We didn’t even have all the equipment we needed – we would show up at our own shows and ask the other bands if we could borrow their gear sometimes, stuff like that. We took the music seriously but we weren’t particularly organized and gung-ho to get in the van and act like Black Flag. We didn’t really know how.

SI: "Codeine had played maybe five live shows by the time we recorded the second side of Frigid Stars LP using the money Glitterhouse advanced us after we recorded the first four songs of FSLP, and played fewer than ten shows before Sub Pop also agreed to put it out. The first time we ever played with Chris it was because he lived in Boston and had drums there, so he could play the Middle East show opening for Bitch Magnet in July of 1989, our first show and the only one we played that year. And he stayed in Boston, playing music with various people, starting Come, etc. NYC is a 5-hour bus ride from Boston, and he made that trip a lot. But it was almost entirely for either recordings or shows, and that was a real hindrance for the band when we started to do more things and want to be more of a real, practiced band.

"Once we started playing with other bands and thinking about what was possible as a band and as musicians, I had much more ambitious desires, as least for the quality of performance. Once Frigid Stars came out we started to do a few more shows, but we were really not rehearsed enough to play out. It would have been much better to wait. I don’t think playing the few shows we did brought much more attention to our music. But we did learn a lot, or at least I learned a lot, about being in a band and what being full time required."

"These days things loom above me/ My head is empty/ My tongue and lips are swollen" – ‘Jr’

Codeine’s second album, Barely Real isn’t just a ‘difficult second’ album. At times it feels as if Codeine are actually resistant to the idea of an ‘album’ altogether. It’s more like a microphone, hung from the heavens and pitched in an inconceivably random arc, swung by where Codeine was happening and captured snatches, hints, moments of where they were at in 1992. Consequently it’s way less ‘whole’ an experience than Frigid Stars; more piecemeal, more stitched together from what fragments could be salvaged.

When it hits hard it does so with an even lusher pop touch than the stark novelty of the band’s debut. A band surer of what they’re doing and consequently more dissatisfied with their own attempts to attain themselves on wax. It’s perhaps Codeine’s un-rockiest album, betraying the post-punk influences that were far more important to Chris and Steven than the punk-rock they were just a little too young to be adherents of – throughout Barely Real there’s a Metal Box sense of space, an Odyshape urge to disappear into oceanic sound.

It is very short – sometimes listed as an EP, not an LP. Barely Real closes out with a cover of an exquisite song, ‘Promise Of Love’ by MX-80 – Bloomington Indiana post-punk oddbods & lost-legends, that pretty much prefigures Spain’s magical ‘The …’ in its entirety. Before that a solo piano piece called ‘W’ recalled the spirits of Satie, Debussy and Arthur Russell – with specific information on the sleeve even scantier than it was for Frigid Stars. At the time I could only imagine where Barely Real came from, and have since only been able to ascertain that certain songs that were recorded for the record were rejected by Stephen. Is this correct? Was it initially going to be a full-length LP? How did David Grubbs’ ‘W’ become part of the record? Are your memories of Barely Real‘s recording happy or not?

SI: "1992 was a very hard year for Codeine. Unlike the two Frigid Stars sessions, all our recording went terribly (or at least, I wasn’t satisfied). We scrapped two studio days trying to record a Sub Pop single-of-the-month club. (The ultra-slow version of ‘Realize’ is on the box set, and we did use the cover of MX-80 Sound’s ‘Promise of Love’.) Then we scrapped a week of days at a fancy studio where we were recording a different ‘The White Birch’, inspired by a painting of the same name by Thomas Wilmer Dewing. We couldn’t get rights to use a photo, and I also wasn’t happy with the results. No one else agreed, but I was convinced we needed to do better. So then we recorded for a week in Alston, MA with me engineering most of the basics on 8-track. Finally, that was fun. Maybe we were meant to record on 8-track only.

"I did the mixing in NYC, without McMackin: we weren’t getting along after the bad studio results (not that they were his fault). And also Chris’s other band, Come, was taking off and playing great shows and he was practicing with them a lot and then had to leave Codeine before we were going to do the European tour. We weren’t mad at him. The way ‘W’ happened was this: we’d done a full-band recording of ‘Wird’ (which we’d scrapped along with everything else from that session) and I wanted Grubbs to do a piano version, although I can’t remember just why I thought he was the person to arrange and play it.

"So I sent him a tape and some notes, John McEntire recorded it in a music room at University of Chicago where Grubbs was doing his undergraduate degree, and then mailed us a DAT. I managed to overcome John’s reluctance to having someone not in the band play one of our songs on the record. I think it turned out really well, and a nice transition from the severity of ‘Hard to Find’ to the jazzy ‘Promise of Love’. It might have been better if that’d been the only version of ‘Wird’ to appear: it’s Codeine’s attempt at a song from Slint’s Tweez, which I somewhat regret."

CB: "The 2nd record was supposed to be called The White Birch. We recorded for a couple of weeks in a nice studio in lower manhattan called Dessau. We ended scrapping the entire thing; Steve was unhappy with the recording. We did some more sessions, and eventually pieced together what became Barely Real. The entire process was pretty difficult, though we were all happy with the album. Some of the Dessau sessions are being included in the reissues on Numero, which I’m very glad about. The best way I can describe it is that we had high aspirations around what we wanted to achieve and it wasn’t always easy (or even possible) to make those happen."

"And as I walk back/I feel the moon against my neck/Loss leader, losing sight of the shore/Can’t take this lost loop anymore" – ‘Loss Leader’

Chris leaves after Barely Real and Doug Scharin enters. The line up of Steven, John, Doug reconvene in 1993 to record Codeine’s last record The White Birch. If you’re just starting on Codeine, I’d start with this 1994 swansong and work backwards – it’s perhaps their most coherent, cataclysmic, perfect statement. At the time, it wasn’t just that Codeine had perfected the balance of heaviness and sparsity that they’d made their own. It wasn’t just that they were developing their ideas into incredible song-structures that expanded and extended the emotional reach and range of their music massively. (There are songs that you presume to be instrumentals, until you realise that Steven’s voice is there, so woven in with the shapes and shadows of the music it approaches total unobtrusiveness.)

It was that, at a time when US rock was equating pain with a kind of noisy, sweaty, Vedder-esque self-indulgence, Codeine were at a total point of remove from the zeitgeist, and consequently closer to our hearts than any other US band working. If Nirvana and grunge were a proudly new-world, gauche look at suffering, a self-piteous solipsistic heaven of self-regard wherein a hateful world destroys innocence and brutalises naivete, then Codeine gave a more old-worldly sense of inevitablity to their dread-laden dirges – their songs are frequently placeless, lyrically between worlds, stranded on ships between past & future, possessed of the informed dread of the immigrant, the impulse to stop moving, to find a new stillness that’s bearable.

Mostly forgotten and bullied out of rock discourse by louder shouts from Seattle and elsewhere, The White Birch is proof that truly original music never yearns for anything as daft as longevity. Rather, their music exists in each moment, each moment entirely dependent on the moments that precede and proceed them. Unforgettable music posessed of an almost infinite evanescence and fragility. Pop like a bubble that seals you in, could burst and break and dissappear into atomised space in an instant.

Steven, throughout Barely Real and The White Birch it seems your lyrics become less about relationships and more about a way of dealing with solitude, or exploring loneliness and memory. The imagery becomes more suggestive, less concrete, more abstract, more mysterious…

SI: "I like the lyrics of The White Birch better, and yes, I wanted to have more writerly songs. And I was figuring out that there were different sources of the same feelings that seemed to inspire earlier Codeine songs. I don’t think we were being mysterious: we even put a band photo on the last album! Actually, designing the records was one of my favorite things about being in a band with John. And I’m still quite pleased with them. With a few exceptions, I’m very proud of The White Birch."

Why did Chris leave? Was it amicable?

CB: "I left the band because 11:11, by Come, was about to be released, and I knew that Come was going to be on tour for about six months, and it didn’t seem fair to either band for me to remain in both. We were all sad about it, but I think those guys understood and supported me in what I wanted to do. We remained friends, Come and Codeine did some shows together after that… it was cool. It sucked, but it was okay."

SI: "We weren’t mad at Chris. Come was doing really well, and he’s a great guitar player. It just took us a while to get another drummer. We did our second European tour (November-Dec 1992) with John Madell, but he was always just on loan from Antietam. The spring of 1993 we put out the word and also had an ad in the Village Voice, and auditioned almost a dozen people while still doing some shows with Josh. The plan was to move to Louisville for the summer to rehearse and then record in Chicago at Idful Studios (where Liz Phair’s Exile In Guyville had been recorded).

"We knew a lot of good people in both cities, and spent the summer playing with Doug five days a week, which was great. We did a bunch of shows and went to Chicago and McMackin came out. But then we had more bad luck with recording. Two different multi-tracks at Idful crapped out, and we resorted to ADAT (a digital 8-track format that could be paired up for 16 tracks). Mike could barely function because of stress. We were able to get three songs out of it – ‘Tom’, ‘Something New’, and most of ‘Wird’. We didn’t come back to the tapes until the very end of 1993, we just went to a place in Connecticut to finish things up and add a few newer songs."

How did things change with Doug?

SI: "The band felt a lot different with Doug. Chris was a musician who could play both drums and guitar, and he was a guitar player first, I think. Doug was a drummer, and an incredibly talented one at that. We played a lot of shows with him, and he was great. And I think he got even better after Codeine, which is very hard to do. He worked very hard, hard at being great in Codeine, hard at being a great drummer.

"Listening to The White Birch remasters really brought it to me: we were very fortunate to have him. The White Birch sounds the way it does because John basically played all the guitar on that record, instead of Chris adding an additional guitar on almost every song. (David Grubbs plays on ‘Tom’ and ‘Wird’ but we unfortunately we didn’t get him up higher in the mix.) At this point, Codeine was even more confident in having less there. I was thinking about this recently: not that many bands have parts of songs that are just spidery guitar, or guitar and vocal. It can be challenging live, and I’ve never been very tolerant of people making noise, so the upcoming festival shows might be difficult. I guess I’ll find out."

The reunion shows have been a triumph, decidedly uncosy, the band still focused with almost supernatural, painstaking concentration on giving every single moment its maximal impact, a reminder of the band’s unique power and revealing of how empty most of the claims of their descendents are.

After The White Birch there’s a nigh-on 20 year gap in Codeine activity (at least that the outside world gets to hear) wherein an awful lot of short-sighted pricks and bad bands cite you as an influence on various genres they’ve made up – slowcore, math-rock, match-core… – did you ever hear anything that made you think, ‘Shit, those guys have listened to Codeine’ in this interim period?

CB: "Of course!"

SI: "I think John and Chris spot influences better than I do, or maybe I’m not looking at the same things as they are."

Was Codeine something you were able to forget about or did people not let you forget?

CB: "I never tried to forget it! It’s part of my past, I’m proud of it; it’s part of who I am.

SI: "Once we started rehearsals for these shows, we started worrying about the (imaginary) Codeine tribute band, Old Things. When we started rehearsing we sounded terrible, and imagined the obstacles facing such a band!"

How has it been playing together again? Is it just purely for the shows or any chance of any new material?

CB: "Playing together has been fun, and strange, and… hard to describe. Mostly, it’s just really fun to spend time working on something again with John and Steve. It’s purely for the shows. if Steve started writing songs again, well, as a fan of his songwriting I’d be very happy and very curious, but, I’m not expecting it. It’s ok for us just to do these shows and spotlight what we did, and the great job that Numero Group has done."

SI: "For the shows, we’re going to play two songs the band recorded but never performed before: ‘Median’ and a cover of ‘Atmosphere’ by Joy Division, both on the reissues. But these shows are really to commemorate the band. So – no weak new songs, no keyboards, no remixes. And no shows beyond those currently on our schedule in the US right now and Japan shows in November. No more shows after that. At least until the next century."

Don’t wait that long to deluge yourself in Codeine’s majesty if you’re still unsanctified. Get the reissues now. Exactly the soundtrack this ‘summer’ deserves.

Next time – what Doug & Chris did next. Rex, Him, June of 44 and the best US band of the 90s – Come

All of Codeine’s albums, singles, Peel Sessions and rarities have been reissued by the Numero Group as the ‘When I See The Sun’ boxset