As the country still reels from the Olympic Games it feels appropriate, on the eve of the film’s theatrical release, to say that Sean Hogan’s latest horror is a Team GB effort to cheer for. Making a film is never easy. Making one in this country is doubly hard. So, in 2010, when Hogan faced serious post-production problems on a project that had no end in sight, he took matters into his own hands and made another damn movie.

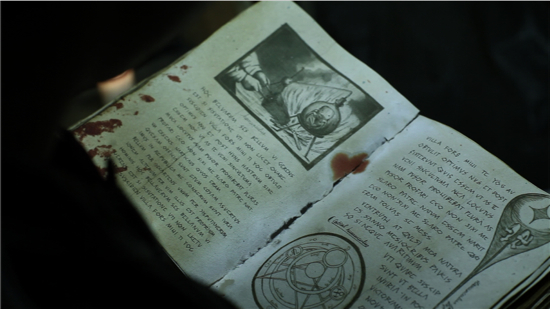

Principally, The Devil’s Business revolves around a time-served hitman, Pinner (played by Billy Clarke, pictured above). He arrives under cover of night with newbie shooter Cully (Jack Gordon) at a large house on the quiet fringes of suburbia. It’s a simple job. Stake out the empty place for an hour or two until Kist (Jonathan Hansler), an old associate of their gangland boss Bruno (Harry Miller), returns, and then execute him.

Pinner is cold and assured from years of killing people to order. He does what he is told and operates on a strict need-to-know basis. He doesn’t question why. He just does. However, his cohort is a bag of nerves. At first Pinner is offhand and aloof, then later condescending as he treats Cully with contempt. No good. Cully keeps asking why they are killing Kist – a flaw in Pinner’s mind if you want to make it in this line of work. More failed attempts to cajole the half-petulant, half-scared younger man follow. This leads to an enthralling monologue by the senior assassin about his life, loves and loathes.

Before Pinner’s tale ends they are disturbed by a noise outside. From this point on, the film’s early gangster posturing distorts into something much darker and more sinister until a finale reminiscent of prime Roman Polanski grabs you for one last scare. Demonstrating through noir staples, meshed with atmospherics that rumble alongside impending doom, that old axiom: you reap what you sow.

The Devil’s Business was shot in just ten days, for very little money. Such energy and drive means that the finished film punches well above the sum of its parts: a four-man cast and single location. This is Hogan’s second full feature after making his writer-director debut in 2005 with the urban ghost story Lie Still. He also co-wrote the 2009 Canadian flick Summer Blood, starring Twilight pretty face Ashley Greene. The following year Hogan penned crime thriller Isle Of Dogs and helmed one of three stories in the challenging sex and horror anthology Little Deaths. His troubles with the latter inadvertently gave rise to The Devil’s Business…

Did you really make The Devil’s Business because Little Deaths stalled ahead of post-production?

Sean Hogan: That’s true. What happened was that we shot Little Deaths in, I think, February and March 2010. It got shut down just as we were going to go into post, so we were twiddling our thumbs, not sure when it would get sorted out. And I had this other script sitting around that I had written to be done before Little Deaths. It was written to be done on a very low budget. My producer, Jennifer Handorf, basically said look, why don’t we just go and make that script – as kind of a palate cleanser.

And did you get your taste for film back?

SH: Yes. I love making films. But Little Deaths, although I stand by the finished film, the whole experience left a nasty taste in my mouth. It was just a very drawn-out, agonising experience. The Devil’s Business really was kind of a punk rock movie. Not in terms of the subject, but in terms of we’re going to do this ourselves. Get a bit of money and do it ourselves and control it ourselves and not have to deal with any of the pricks we’ve had to deal with in the past.

Why mix film noir and horror genres?

SH: Film noir itself is usually about these very flawed characters where over the course of a movie they’ll meet their doom. Usually because of things they’ve done in the past – pigeons coming home to roost, where past misdeeds catch up with them. The Devil’s Business is very much that kind of film. It just takes a sort of horror approach to it.

Is this really a horror version of Harold Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter?

SH: Yes. The Dumb Waiter is kind of a noir version of Waiting For Godot. It’s that similar sort of existential thing of people waiting around and not really knowing why they’re there. And there was definitely that aspect that appealed to me. I thought just take that whole existential thing and run with it. That’s why in this film you’ve got the guy, Pinner, who is all about following orders because that’s how he believes you should live life. And then he finds that maybe that’s not the best way and it’s led him down a road of damnation, as it were.

What was it about Billy Clarke that captured Pinner?

SH: Aside from obviously being a good actor, which he is, there was just something about his face that really got me. In the 1960s and ’70s you had actors who looked like they’d lived a life. And that was kind of what I got from Billy. In real life he’s a really sweet, gentle guy.

The lengthy monologue by Pinner is impressive. Was the first take really his best?

SH: A lot it is down to Billy. We did do other takes, but on the first take he did just sail through it. And got a round of applause afterwards. If I’d cast the wrong guy to do it, it could have fallen completely flat. But hats off to him, he nailed it.

Did Jack Gordon pretend to be Cully off camera?

SH: I think Jack went a bit method on us. We were shooting 4pm to 4am every night. To wind down at the end, me, Jen, Jack and Billy would have a beer or two at 5am. And Jack came out with all these stories about how he’d lived a life that was quite similar to his character. How he got into trouble at school; his dad had gone down and threatened to beat up a teacher – real Jack the lad stories and we were like wow, what a coincidence. Jen spoke to his agent afterwards about it. He was like, [that’s] nonsense! Jack is a nice middle-class boy. He’ll probably hate me for saying this but he got rumbled, unfortunately.

How did you resist showing more gore? For example, during one particular death scene you focus on the look of horror on another character’s face.

SH: To be honest, given the nature of what is meant to be killing him that’s something we wouldn’t have been able to achieve on our budget. What I had in mind for that was very much a scene from The Leopard Man [the Val Lewton-produced 1943 picture] where the girl gets ripped to pieces on the other side of a door and you’re seeing it play out on the mother. In the end you just see the blood dripping under the door and it’s really, really effective. It’s a style of filmmaking I like. Where you don’t have to show everything. Yes it does help out for budgetary reasons, but equally sometimes what you don’t see can be massively effective. And that was really the way how the whole film was going to be set up. I do love movies that are about the power of suggestion – as much about what you don’t see as what you do.

You’ve talked in the past about 1970s movies using genre frameworks as a means of experimenting in cinema. Any examples you would recommend?

SH: Something like Night Moves is one I watch a lot. It is a film noir crime movie, but uses that to approach much larger existential themes. A horror movie that springs to mind: Let’s Scare Jessica To Death. Which on the one hand is a genre movie, but on the other is about one woman’s mental breakdown. It just seemed to be a time when you could use these genre frameworks as metaphors and discuss things beyond the fact that there are monsters or whatever else. It was just an interesting time.

The Devil’s Business opens in selected cinemas nationwide this Friday August 17, with a DVD release to follow on September 10 via Metrodome Distribution.