In 1984, Giorgio Moroder released his newly restored version of director Fritz Lang’s silent 1927 sci-fi blockbuster Metropolis. In stark contrast to various scholarly restorations before and since, the pioneering Eurodisco producer colourised the film’s monochrome palette, adding special effects and explanatory intertitles, then slathered the whole package in a throbbing synth-rock soundtrack featuring Freddie Mercury, Bonnie Tyler, Adam Ant, Loverboy and other stupendously naff 1980s icons. In his BFI Film Classic booklet on Metropolis, Thomas Elsaesser calls Moroder’s version "somewhere between a remake and a post-modern appropriation". More than that, it was the first ever disco remix of an entire movie.

Some waggish reviewers advised film fans to wear earplugs to see Moroder’s Metropolis. At least one cinema screened it with the volume cranked down to zero. In fairness, these clunky stage musical-style numbers were never Moroder classics, and on revisiting the film for its British DVD debut, they have not aged gracefully. You can practically hear the mullets and designer stubble squeaking through the speakers.

Of course, snooty modernist ponces like myself already have a fantasy version of Metropolis in our heads that unspools to the cool glide of Kraftwerk, Philip Glass, Model 500, Yellow Magic Orchestra, Michael Nyman, John Foxx and Autechre. But Moroder’s splashy MTV makeover is arguably much closer to what Lang’s overstuffed Expressionist epic deserves, with its heavy overtones of cheesy melodrama and totalitarian kitsch.

Metropolis was written by Lang’s aristocratic wife Thea Von Harbou, a pulp novelist and future Nazi Party member. It takes place in a dystopian future mega-city whose workers toil in subterranean misery until Freder, the idealistic son of the city’s haughty patrician leader, falls in love with the charismatic working-class beauty Maria, leading him on an undercover mission among the oppressed proles. Meanwhile, Freder’s father enlists the maverick alchemist-scientist Rotwang to create a robot clone of Maria who will lead the workers into a self-destructive uprising. Following cataclysmic floods and fatal confrontations, order returns to Metropolis only when Freder persuades his father that compassion is a better way to rule than cruelty.

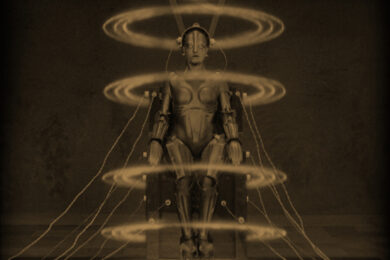

Almost a century later, it is the jaw-dropping visual spectacle of Metropolis that has far outlasted its infantile, muddled, fable-like plot: the super-sized Expressionist skyscrapers that predicted a century of thrusting urban architecture; the uniformed worker-slaves marching in zombie-shuffle unison; the cyborg Maria emerging from a pulsing tower of Saturn-like electrical rings; the lone worker crucified on the giant clockface controls of his monstrous industrial machine; the Tower of Babel dream sequence that brings Brueghel’s canvas to life. Shot on an epic scale over 16 months, with 36,000 extras and an ever-ballooning budget, Metropolis still looks amazing.

Written in the wake of World War I and the Russian Revolution, Von Harbou’s script for Metropolis is inevitably slanted by its immediate political and social context: Weimar Berlin in full decadent flow; escalating street battles between right and left; the machine-age industrial modernism of Henry Ford; the sleek urban geometry of Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus school; the faint malevolent hum of fascism on the rise. But it is also densely packed with Christian allegory, Eastern mysticism, Germanic folklore, allusions to Frankenstein and The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, plus a hefty dollop of hammy dime-store romance.

Watching Metropolis in 2012, the political message feels comically banal but still a little queasy. I was reminded of the 1977 essay ‘Starship Stormtroopers’ by the veteran anarchist and science fiction author Michael Moorcock, which blasted many of the biggest names in science fiction and fantasy literature as "bourgeois reactionaries to a man, Christian apologists, crypto-Stalinists… there is Lovecraft, the misogynistic racist; there is Heinlein, the authoritarian militarist; there is Ayn Rand, the rabid opponent of trade unionism and the left who, like many a reactionary before her, sees the problems of the world as a failure by capitalists to assume the responsibilities of ‘good leadership’…"

Moorcock does not mention Metropolis, but his critique fits perfectly here. Ayn Rand’s pernicious brand of paternalism runs deep in Lang’s film, which depicts a technocratic pharaoh ruling over the bovine proletarian masses who toil away in the city’s bowels, childlike and excitable, microscopic pawns in his catastrophic plan. The script’s fatuous final message, that "the mediator between the head and hands must be the heart", is a trite affirmation that all social classes should stick to their place in the hierarchy. The divine right of the ruling class elite to remain in charge is never in question.

The film’s depiction of women is also feverishly silly but slightly creepy. A dual role for the 19-year-old screen novice Brigitte Helm, the division of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Maria is classic Madonna-whore complex, equating liberated female sexuality with a rupture in the natural social order, which is only resolved when the erotically mesmerising femme fatale Maria-robot is torched at the stake. Burn the witch! There is also a strong whiff of anti-Semitism in the vengeful mad-scientist figure Rotwang, invoking dubious Jewish archetypes in European folklore. He too must meet a violent end before order is restored to Metropolis. It comes as no surprise that Von Harbou later embraced Nazi ideology.

But Metropolis was never a proto-Nazi work, despite what some critics later claimed. Hitler’s propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels may have paraphrased lines from the script in a 1928 speech, and the film’s stunning visuals would later find echoes in Leni Riefenstahl’s big screen fascist spectacles – but Lang also went on to make the explicitly anti-Nazi thriller The Testament Of Doctor Mabuse, and finally fled Germany in 1933, leaving Von Harbou behind. His movies were eventually banned, with Nazi critics attacking their ‘alien’ ingredients – in other words, Lang’s partly Jewish blood.

Contemporary left-wing commentators were equally scathing about Metropolis. Lang’s film may have been banned in Italy and Turkey for its ‘Bolshevik tendency’, but the Communist critic Felix Ziegel dismissed it as "born out of a bourgeois-capitalist ideology… unmasking the bourgeois worker-friendly phraseology in all its mendacity." The British socialist sci-fi pioneer HG Wells saw only "foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress" while the Spanish Surrealist filmmaker and sometime Communist Luis Buñuel slammed its "trivial, pretentious, hackneyed romanticism."

Launched to great fanfare but lukewarm reception in Berlin in January 1927, Metropolis was both a critical and commercial flop. It was heavily re-edited for UK and US release, losing more than a third of its full three-hour running time. It then fell off the radar for decades, a notorious folly tainted by its lingering Nazi associations, for which Lang repeatedly apologised. Some scenes were lost forever, buried in far-flung bunkers on volatile nitrate reels.

But the film amassed a growing cult reputation, largely on the strength of its prophetic visual imagery, as the political context receded and the late 20th century urban landscape increasingly came to resemble Metropolis. A new generation of directors paid explicit homage, from the shiny humanoid contours of C-3PO in Star Wars to the hulking future-noir architecture in Blade Runner to the techno-gothic high-rise cityscapes in Tim Burton’s Batman, Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element and many more. Meanwhile, various film scholars attempted to assemble ‘definitive’ restored versions, screening them with orchestral or electronic scores. Lang’s grand folly became respectable again.

Ultimately, Giorgio Moroder did Metropolis a huge favour, rebooting a dusty old relic of the silent age for the MTV era, sweetening and streamlining its confused morass of plots just enough to make it comprehensible to modern viewers. Thanks to the Italian-born, Munich-based disco king, Lang’s budget-busting folly enjoyed its first ever commercial success. The film also belatedly found its true pop-culture calling as the world’s first feature-length music promo, directly inspiring the lavish videos for Queen’s ‘Radio Ga Ga’ and Madonna’s ‘Express Yourself’. More recently, R&B star Janelle Monáe’s futuristic 2010 concept album The ArchAndroid was heavily based on Metropolis.

Two years ago, a new ‘definitive’ cut of Lang’s visionary Expressionist epic was issued with more missing scenes restored and a full orchestral score. It was sombre, serious, scholarly – and deadly dull. Moroder’s postmodern remix may have a tooth-achingly awful soundtrack, but it is colourful and kitsch and, crucially, wastes little time on Van Harbou’s preposterous and reactionary plot. Flawed though it may be, Moroder’s Metropolis is still one of the best bad films ever made.

Giorgio Moroder Presents Metropolis is out now on DVD through Eureka Entertainment and as a pay-per-view stream at the Metropolis Movie website.