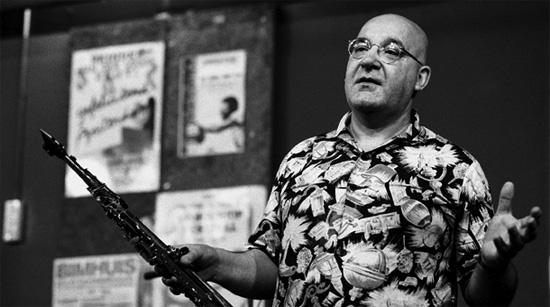

Discovered busking by John Peel, saxophonist Lol Coxhill – who died last week at

the age of 79 after a lengthy period of illness – was a jazz musician

unconfined by limiting notions of what jazz is, and whose career spanned

everything from truly free free improv to spoken-word to appearances on

albums by artists from Kevin Ayers to The Damned. A Great British Eccentric

of an increasingly rare breed, he is irreplaceable.

Bill Wells, a similarly jazz-not-jazz (i.e. jazz in the purest sense) musician, was recently

– alongside Aidan Moffat – the winner of the inaugural Scottish Album of the

Year Award for 2011’s Everything’s Getting Older. The recognition is long

overdue for a unique musician whose indiosyncratic but always deeply

melodic, understatedly romantic muse floats somewhere between Bacharach,

Bill Evans and Eno, and whose classic album Also In White celebrates its

tenth anniversary this year. The record Bill and Lol made together – 2001’s

The Bill Wells Octet meets Lol Coxhill – was only ever available on vinyl. Courtesy of Bill, we’re pleased to be able to offer a download of a track from the album, ‘Phantom Pain’, available for the first time digitally. You can get it via the embed below.

The Quietus spoke to Wells about his history with Coxhill’s music, collaborating with him, and his respect for a man he calls "my total hero".

One of the things you have in common with Lol is a love of Kevin Ayers [Wells

appears on Ayers’s 2007 album The Unfairground, along with Roxy Music’s

Phil Manzanera and members of Teenage Fanclub, Neutral Milk Hotel and

Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci]. Would I be right in thinking you came to Lol

through the Kevin Ayers records – Shooting At the Moon, The

Confessions of Dr Dream – he played on?

Bill Wells: Yes, yes. Realising – well, he looks a quirky character on the [back]

cover of Shooting At The Moon. Then I got Ear of the Beholder, which

was his first album under his own name.

John Peel released it on Dandelion. In the US records that didn’t sell were

sent back as cut-outs, with a big stab in the corner – I got it as a US

cut-out. I remember thinking it was one of the strangest records I’d ever

heard in my life; some of the worst quality recordings I’d ever heard on a

record at that point. It was quite shocking – almost like field recordings.

…but liberating too?

BW: Yes. [The idea that] you could do that on a record. I’d probably been

listening to Simon & Garfunkel or something – studio quality things. He

introduces it too: ‘This is my record, I really like some of it, I don’t

hate any of it’ [laughs] A self-depreciating kind of thing that’s quite

charming. There’s a version of ‘I Am the Walrus’ sung by children! It’s

charming but a little disturbing as well.

That’s always a good combination!

BW: Yes! It’s strange because there’s no chords on it, no harmonies – just

their voices, [singing] the way they learnt it from the record, just

maracas keeping it going. There’s some of his stuff with David Bedford – he

did these Victorian music hall songs, some of which are really awful, but

he did them to highlight how totally racist they are: ‘That’s why darkies

are born’!

He occupies a space in my head that’s not unconnected with The Flying

Lizards.

BW: Yes, yes. Absolutely. So that record is a great showcase for what he’s

about. It’s a double, a kinda sprawling thing – there’s a side that’s a

20-minute improvisation. You can get it on CD.

Then I went to see him, quite early on, not long after hearing that – he

played in Glasgow; this would have been in the 70s. He had a piano player;

it was in what was then the Third Eye Centre – now the CCA. I don’t

remember much about it to be honest, but I do remember him saying ‘I was

gonna play ‘Lover Man’ but I don’t think I will.’ And someone shouted out

‘Nice tune!’ So he did it. So that really made me…

…warm to him?

BW: Yes. That he would do something that spontaneously, just react to what

somebody wanted: to give them that.

Um, this isn’t meant to be a rude question, but how old were you at this

point? [Wells erupts into raucous laughter] I mean – there is the enduring

enigma of exactly how old you are…

BW: [chuckling]

I mean… loosely. Within… a decade…

BW: Well – you see the thing is… just between you and I…

It can be off the record!

BW: [further chuckling] You see, on the internet, there’s this date of my

birth. And it’s not the right date! So, do you change it or go along with

it? It is quite hard doing pop music as you’re getting older. Ultimately I

don’t mind, but sometimes I do think you’re making it harder for yourself…

That’s partly what’s great about Everything’s Getting Older, the album

with Aidan – and those terrifying pictures of you as prune-faced geriatrics

on the cover…

BW: Well, I’m probably nearer to [actually looking like that]!

Oh, stop it! Actually, Aidan’s beard is getting really grey. It’s much

greyer than when I first knew him.

BW: [laughs] yeah! Yeah! So just to tell you, just so I’ve told so, I’m [censored].

We will never speak of this again. That information will never leave this

room. I’ve had this conversation with so many people: how old do you think

Bill really is? And there’s that thing of it being hard to imagine you as a

child, I kinda think of you as manifesting suddenly, just as you are now.

Like Mr. Benn.

BW: [laughing] Yeah! So, say I was in my mid-teens discovering Kevin Ayers.

Did you come to pop music – or whatever you call Kevin Ayers – before you

came to jazz in a purer sense?

BW: Yes. Well, I was really into John McLaughlin, who’d played with Miles

Davis. So I started playing Miles Davis records. I bought Live Evil because

he was on it. And he plays the most amazing solos. It was basically my key

to jazz, because I so loved the records, I started buying everything by

Miles Davis. That took you everywhere you wanted to go – it took you back

to Charlie Parker, [the cornerstone of] modern jazz. Then you’d find people

who’d played with him – and he’d played with pretty much everyone.

Was Lol the first jazz – however loosely you might call him jazz –

performer you’d seen live?

BW: Aye. I suppose, yeah. I was more interested in people playing pop music

[then].

I actually didn’t realise he had a small part in Derek Jarman’s Caravaggio – which is sort of British avant-garde 101.

BW: [laughs] yeah.

He played with Shirley Collins, he played with Hugh Hopper – he played on

The Damned’s Music For Pleasure! It feels a little bit like when Derek

Jarman died – that we’ve lost one of those few remaining great figures of a

particularly British experimentalism, that has a very capricious

relationship with restrictive things like, say, genre.

BW: Aye, yes. It’s not like you really feel there was anyone in the next

generation coming up to do the same kind of thing. He was totally a

one-off. And free in the truest sense, in the way that most ‘free’ and

improv musicians aren’t – he would use anything: if he felt like using a

bit of a song in the middle of something, he would do it. True freedom. He

would play anything – not this restricting ‘free’ improv thing where it

can’t have a melody, it can’t have a definite rhythm.

He’s got that thing that Richard Youngs also has: a deep sense of grace

that sets him apart from all that god-awful droning and scraping that sets

itself up as being on the edge of something. The conservatism of the

self-styled avant-garde!

BW: Yeah. And it made him unpopular with some of those people.

That’s something I imagine you identify with…

BW: Totally. To me, he’s my model of an ideal musician. He could play with

this whole range of people and he would fit in, but sound completely like

himself – and what more can you want?

Bill Wells with a copy of the album he made with Lol Coxhill

How did you come to make a record with him?

BW: The next time I saw him was at the Glasgow Jazz Festival in 1994 – when

they were still open enough to put on that sort of thing. He played with

Pat Thomas – a keyboard/electronics guy – well, he’s a virtuoso piano

player. An amazing guy! That was [eventually] released by Liam Stefani – he

promoted gigs, and ran this label Scatter from Glasgow. His first release

was a Derek Bailey thing – I think the second one was the Lol/Pat Thomas

show.

In about 2000 he put on a gig with Pat and Lol, and asked me to

support, or asked Lindsay Cooper to play support, anyway – we supported. I

remember Lol being quite reserved, and Pat was this larger than life

character with a huge laugh, not what you expect from a free improv guy.

He was roaring with laughter all the time. We ended up playing all

together, the four of us, at the end. I think it was after that I asked him

to do it. Raymond MacDonald, who runs the Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra,

and George Burt started a thing around then.

It was basically recorded in a day.

That’s jazz!

BW: [laughs] Yeah! The title was kind of a joke: The Bill Wells Octet

Meets Lol Coxhill. Because it wasn’t an octet at that point, and we didn’t

meet – well, he met me. My main instrument at the time was the sampler – I

was kind of obsessed with it. When I supported Pat and Lol with Lindsay I

just used the sampler. I became quite fluent with that Zoom thing. I was

quite intimidated on the night because Pat had a whole table of gadgets,

including a Zoom, but by the end of the night he said, ‘By god, you’re

really getting around that thing!’ He was also, I think, quite impressed

that I wasn’t part of the Scottish jazz mafia…

I wanted to make this record, and I had all these loops. I recorded Lol in

the East Kilbride Arts Centre with Davy Scott [of the Pearlfishers and

latterly BMX Bandits]. I played the loops and Lol played on top of them.

Then I put the ‘octet’ – three people and me on piano – on top. It’s a

weird thing to do, because Lol only heard the loop, so if there’s a melody

there he didn’t [hear it or have the chance to respond to it]. [laughs]

People would say, Wow, his playing’s really out there! He’s really gone

out there! [And] it really is [out there]! I’m really proud of it, but in

a way I feel it didn’t quite come off… it’s an attempt at doing something…

…that’s quite true to the spirit though..?

BW: Yes. I do think that despite my reservations about our record together,

it features some of Lol’s best playing, I’m just disappointed that the

octet he plays with is more like a ‘cardboard cut out’ of the band rather

than the actual band and then, when there was the chance to play with the

actual band live, because of just very pragmatic considerations, that

didn’t really come off either.

There’s an Eno aphorism about the value of mistakes that’s applicable here,

isn’t there?

BW: Yes. It’s almost like the demo of the record I wanted to make. It did

get enough attention that I could put on a gig with Lol and the [actual]

octet. That was like the realisation [of what I’d wanted the album to sound

like].

Did you record it?

BW: I did. But the gig was a bit of a disaster! [laughs]

I realised as the gig was unfolding how difficult it was to have an eight-piece band playing

along with a sampler! After about 30 seconds in, the sampler was in one

space and the rest of the band was heading off in another direction…! What

can you say? At least I tried. The loops are… a bit quirky. Probably not

the easiest thing to keep in time with. Also in that band I had Isobel

Campbell [laughs] and Stevie Jackson, who had both travelled down from

recording with Belle and Sebastian, it was about a year before Isobel left.

She was on piano.

It was just such a strange [band]. I must have been

playing… [thinks] electric bass, in the hopes I could pull the whole thing

together. But it did have moments… Lol wasn’t very well – he described

himself as feeling as though he was walking along this tightrope during the

gig, with a huge drop on each side. The whole thing was absolutely bizarre.

It was part of a really strange weekend. Having him up here, I thought I

should get him another gig.

I didn’t want to do the same thing on two

nights, and at the time Channel 4 were doing all those list programmes – so

I thought I’d do 50 Greatest Riffs. I’d no idea it was going to be such an

enormous amount of work – to edit them and assemble them. It was another

bizarre gig – what a weekend it was, I had my total hero there and all

these gigs were going wrong! I had Raymond and George and Allen Beauvoisin,

who was in the octet, along to play with Lol. I gave them two instructions,

because I wanted the gig to last 50 minutes, it was already quite busy with

all those riffs, and I only wanted to play each one for a minute – so I

said, ‘Don’t play all the time,’ because I had three saxophone players

there, and ‘when the riffs stop, stop playing.’ And they ignored both of

these instructions! [laughter]

A few after that, Nick from Directorsound – they had a record on [the Pastels’ label Geographic] – was up for the Triptych Festival, and I described this gig, he said ‘it sounds

fascinating, have you got a recording?’ I couldn’t listen to it – it had too

many bad memories! They thought it was amazing, and released it as a CDR.

Your own experience of something can colour what it actually is. With the

passage of time, I can hear it and think of it as good.

Did you keep in touch?

BW: There’s another record we played on together; he’s on three of Raymond

and George’s records. But unless you were actually asking him to work for

you, he was hard to keep in touch with. He was so busy, he knew so many

people – maybe not as much as he wanted to be, although he’s very well

documented. I tried to get him for a one-off gig last year, and to play

with Bridget St John this year, but by that time he’d become ill.

To go back to that weekend, I’d booked a studio for the next day, and I

didn’t know what we were going to do – but me and Lindsay Cooper and Lol

went in. Lindsay is kind of like Lol – but he just doesn’t have the same

recorded legacy. I always think of him as part of that whole… Derek Bailey

[scene]. I should really mention John Cavanagh who is, to me, another

marginalized figure on the Scottish scene: he was, at my request, MC at the

gig in January this year with Bridget St John and has been a big fan and

supporter of Lol ever since I’ve known him.

Anyway, Lol and Lindsay had never recorded together – so I just let them

play. Lindsay was great both on tuba and double bass – there are two

ten-minute improvisations. I just basically let them make the record

together. I held on to the recordings, thinking one day I’ll let folk hear

it. It’s like a conversation, like hearing old friends talking, having a

good old blether. I think that night we played with the [Bill Wells] Trio,

and I met Stefan Schneider [of To Rococo Rot] for the first time. It was an

incredible weekend. I remember playing Lol’s stuff back to him, and he

started playing along with himself – I almost had to leave the room: it was

overwhelming.