"Is guitar music dead?", asked the Guardian music community yesterday, recycling for the umpteenth time the age-old dichotomy that journalists seem to love to impose upon the worlds of rock and dance. A thoroughly redundant question to ask at this point, certainly, but on one level at least its underlying sentiment has a point: electronic music seems to be worming its grubby way everywhere at the moment, with a host of synthetic variations lapping their way right to the shores of the mainstream.

Some are excellent, some markedly less so. It was heartening last year to witness the success of Katy B’s On A Mission album, a smart and witty synthesis of the last fifteen years of UK urban and underground dance music. On British shores, varying strains of two-step informed indie have emerged in the wake of dubstep (well, in the wake of Burial, let’s be honest), making for a refreshing – if already formulaic – alternative to ‘Peter’ Doherty’s snide and narcissistic urchin indie and Later… style weepy balladry.

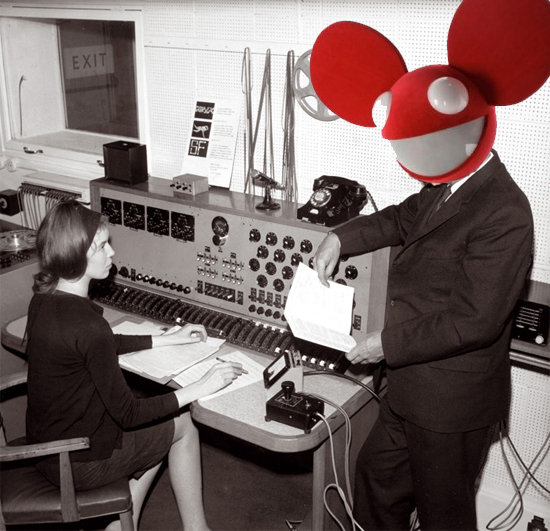

Elsewhere, though, the hoovering up and spitting out of ten year old trance riffs and massive, bolshy builds has been tearing the fabric of pop and R&B to pieces and making merry in a total vacuum of meaning or emotion, in a tendency Dan Barrow identified last year as ‘The Soar.’ That appears to have reached its nadir in the unprecedented rise, in the States, of what people are referring to as ‘EDM’: Electronic Dance Music as shorthand for Skrillex’s grotesque, splattery dubstep, the predictable stadium electro-house of Deadmau5 and the knuckleheaded lumberings of the (thankfully now disbanded) Swedish House Mafia. It’s something that veteran electronic music journalist Philip Sherburne has been covering in some detail in his column over at SPIN, an archive well worth reading through for coverage of what’s turning into an increasingly global phenomenon.

These are clearly the thought patterns that lie behind EMI Music’s launch of their Electrospective campaign last week, accompanied by a statistic from their consumer research department that "dance/electronic music [is] the third most popular music genre globally, with particularly high interest among 16-34 year olds". From now until November, EMI will be running a multimedia campaign "celebrating the development of electronic music since 1958 and the earliest days of technological innovation at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop", via a double CD compilation, promotion of classic albums, a round table discussion event in London, competitions, articles, et al.

The Electrospective website has already launched, and features a chronological list of what it deems to be key albums and events along the way, from the forming and debut release of German pioneers Can, through the development of the Moog synthesiser, to classic records from Kraftwerk, Giorgio Moroder, Frankie Knuckles and so forth up to 2012. Given the proliferation of easy-to-acquire music software and an attendant explosion in the number of people producing and releasing electronic music, or at least using minimal means to maximal effect, it seems a reasonable enough time to take stock of where the development of synthesised sound has taken humankind by the year 2012. The inclusion of pundits like Mute boss Daniel Miller and Detroit/Berlin techno minimalist Richie Hawtin lends the project extra weight, as does the inclusion of the body-battering likes of Nitzer Ebb, and those, like Yazoo and Duran Duran, who skillfully straddled the worlds of pop and experimental music.

One question worth asking off the bat, though, is whether the idea of encapsulating nearly half a century’s worth of technical and compositional innovation in the space of a double CD and a slick marketing campaign is fundamentally flawed. Certainly the use of the term ‘genre’ here as an attachment to the label ‘electronic/dance music’ sets off warning alarms; with a term so broad now as to be functionally useless, where will Electrospective’s curators decide the boundaries be drawn? The gaping holes in the compilation’s tracklist speak for themselves. Although the project’s stated remit is broad to the point where The Beastie Boys can rub shoulders with Paul Oakenfold and Jean Michel Jarre, and its aim is to "[bring] together the key moments in the development of electronic music", from the 90s onward its worldview noticeably narrows, and in the wake of the Chemical Brothers’ stadium dance descends into an increasingly insipid series of chart-bothering megahits: Moby’s Play; Daft Punk’s live album and Tron soundtrack; David Guetta.

The problem is partly inherent to the subject matter, of course: how could one single list possibly hope to represent so many different narrative strands? But the real issue with this timeline – and the tracklist of the CD that it extends to – is that it presents electronic music since the mid-90s as a monoculture, a single lineage which has supposedly reached its pinnacle thus far with the glassy eyed, vaguely misogynistic rock star antics of Swedish House Mafia. For anyone with even a passing interest in electronic music in the last ten years, the idea is so ridiculous as to be laughable. It’s like defying commonly accepted laws of physics by watching evolution unfold in reverse. Or, indeed, like using the term ‘guitar music’ to encapsulate every different form that’s ever incorporated a six-string player, then suggesting that its best representatives from the past decade were Kings of Leon, or Mumford & Sons, or Kasabian.

For younger listeners having a quick listen through Electrospective, it’s as though entire past two decades of UK hardcore continuum music might never have happened at all: the rave movement of the late 80s/early 90s is only hinted at in the bristly percussion of Future Sound of London’s ‘Lifeforms’; jungle, still the most extreme and futuristic form of dance music ever to move a club crowd, doesn’t appear at all, save as a ghost in the fluid drum & bass of Adam F’s ‘Circles’. Similarly, UK garage and 2-step, grime, dubstep, funky – all are notable by their absence.

Although it’s never made explicit, and though it’s not like earlier inclusions like the late, great Fad Gadget were ever particularly commercially successful, the list admittedly seems to focus more intently on the moments when electronic music seeded in the underground made inroads into the mainstream. That would explain why Chicago and Detroit’s house and techno pioneers barely get a look in – save Kevin Saunderson’s brilliant ‘Big Fun’ – even though their eventual descendants dominate the latter half of the list.

But even then, what makes Goldfrapp, The Beastie Boys and Gorillaz worthy of inclusion where Wiley, Missy Elliott and Timbaland are nowhere to be seen? In the 90s, Stateside R&B producers were infinitely more sonically and texturally innovative than the majority of people who would happily have labeled themselves ‘electronica’, and its influence has loomed large over club music since. Similarly, of all the music that emerged in the wake of UK garage, it was grime that hosted the most dramatic reinventions: Wiley’s ice cold early instrumentals set the template for a brittle, alienated and future-shocked form of dance music whose inventiveness, wit and importance has been sadly downplayed thanks to media hyperbole and over-zealous police activity. If you’re tracking the development of smart and uniquely British electronic pop music since the early days of Mute, Wiley’s pairing with Dizzee Rascal on Boy In The Corner was a truer descendent to the caustic sounds of The Normal or Cabaret Voltaire than anything represented in post-millennial Electrospective. (A reminder: it also invaded charts and mainstream clubs, won a Mercury Prize and established Dizzee as a festival-headlining household name.)

For fans, critics and musicians alike, the appeal of electronic music over the past few decades has been in its breaking down of established boundaries. Technology is certainly one facet of that, something alluded to on Electrospective’s timeline, which as well as the Radiophonic Workshop has included the likes of Beatport and ubiquitous performance software Ableton Live. But the opening up of technology to an increased number of people, and its implications for human interaction, have had revolutionary consequences in the past: disco and house was born in gay black communities and was catalysed by social injustice, poverty, oppression and illness; club culture took the rockist emphasis off the DJs and onto the crowd.

Combined with ecstasy – especially during the rave movement – that turned places of performance into open spaces where different strata of society were able to collide. That set of conditions enabled UK dance music to develop into the glorious, multi-limbed hydra we see today, whose roots and interests stretch from London to the US, Jamaica and Africa. Here, that vitality is boiled down to a list of acts accustomed to playing to audiences of tens of thousands, representing rigid and increasingly formulaic approaches to an already well-worn sound. Where did it all go wrong? Fuck it, just hit ‘stop’ halfway through the second disc and save yourself from having to worry about it.

There’s nothing essentially wrong with the Electrospective project. Though it’s clearly a neat way of drawing together the back catalogues of EMI, Mute and Virgin for some extra sales (via their online shop), there’s no shortage of gems in their collective archive, incorporating a far wider variety of great artists than those included on the compilation. And don’t get me wrong – crimes have been committed in the name of so-called ‘intelligent’ dance music, so the argument here isn’t that there’s any intrinsic problem with stadium electronic music or those who listen to it. But these later examples on the CD are inherently musically conservative, and to place them at the post-2000 end of this lineage is to misrepresent the open-minded approach of those that preceded them.

By painting the last few years as an evolutionary dead end, they do a disservice to the volumes of recent music that keeps the attitude of its forebears intact, and still manages to capture the interest of listeners well outside the confines of the underground. Instead of choosing Deadmau5’s Random Album Title for 2008’s nominee, for example – an album well summed up by its tossed off title – how about Portishead’s Third, which pushed past the trio’s 90s output into caustic and claustrophobic territory? Or perhaps better, The Bug’s London Zoo, whose combination of bass weight, firestorm distortion, razor-sharp pop nous and biting social commentary on multicultural urban Britain has made it an acclaimed modern classic? Or for 2007, Burial’s Untrue: nominated for the Mercury Prize, made the subject of an unmasking campaign by The Sun, and one of the best albums of last decade?

The list could continue ad infinitum; the last ten years deserve better than Guetta, Angello, Prydz and co, and if any casual listener were to extrapolate forward from that rabble, the view of what’s to come would be grim indeed. A friend of mine is fond of paraphrasing Orwell’s 1984 when talking about the proliferation of done-to-death drum machine facsimiles in current bass music, but it’s as easy to do the same here. Want a vision of the future according to Electrospective? Imagine crap trance riffs and recycled one note basslines stomping on a human face, for ever.