International football tournaments come around so quickly these days. Maybe it’s a consequence of getting older, but the PASSION!-themed TV advertising seems to start as the ears are still ringing with the previous competition’s sententious punditry. Sure enough, I’m still recovering from my twenty-ninth birthday – involving a Pennine reservoir’s-worth of booze and a 2010 World Cup quarter-final penalty shoot-out soundtracked experimentally with Mahler’s Tragische Symphony No. 6 – and the Poland-Ukraine European Championships are getting underway. The media are microwaving their xenophobic patter, and part-time fans across England are consulting their WKD sides to escape those long-scheduled family christenings to watch the group matches down the local. Banter, endless bloody banter, drifts through the window on the breeze to chisel away that vestige of the life-force left intact by the Jubilympics. It must be hellish if you don’t like football.

In fact, it’s not entirely pleasant if you do, or do in a way that exceeds donning an England shirt and yelling at a pub television every two years. As someone who spends a substantial amount of time watching lower-league football, my haughtiness towards international tournaments is akin to that of a Detroit techno connoisseur offered a guest-listing for a Scooter show. While the standard of play at World Cups and Euros is typically exceptional, and the drama of the competitions undeniable, it’s hard not to feel that a misappropriation occurs during them. It isn’t that I believe sport is ruined when it becomes a vehicle for collective expression – quite the opposite, in fact – but that football loses its subversive capacities when coloured by nationalistic ideology.

Unfortunately, it’s at precisely the moments that football becomes especially visible to its detractors that it most closely matches their perception of it as an arena of loutish behaviour and ungainly sentiment. On many occasions, I’ve implored a sceptical friend, full of justified ire at hearing stories of (for example) foreign students being attacked after another disappointing tournament elimination for England, to believe me when I tell them that it isn’t really like that. And it isn’t: dichotomies between ‘boorish’ football and civilised behaviour are premised on an unfair caricature.

This isn’t, I should add, a Nick Hornby-derived theory. In Fever Pitch, the 1992 book widely credited with ‘liberating’ football from the clutches of hooliganism and delivering it a new audience of sensitive aesthetes, Hornby brought cheese-course conviction to the notion that a life well-lived could accommodate both a comprehensive understanding of John Updike’s sexual worldview and trips to Arsenal. Essentially, it was a manual designed to assist Guardian readers to justify the fact that they occasionally tuned into Match of the Day. It was, at best, problematic.

Those who despise the game and the Hornbyites set up two positions. The first portrays football as anything from a pointless waste of time to a pernicious vehicle of false consciousness, a post-religious opium of the people. The second revels in football’s supposed primitivism, situating it in opposition to, say, theatre or art cinema. My sense is that both of these arguments lack credibility, and that the sport offers in its own right a way towards social and cultural awareness. Scratch beneath the surface of its mass-media incarnations, the vaguely Rollerball-like Sky Super Sundays and the overstated laddishness of Soccer AM, and it becomes apparent that fan culture is characterised by an organic political intelligence.

The ability of supporters to mobilise themselves in resistance to what they regard as the theft of the game by business disabuses their widely-held reputation for quietism, a myth propagated by both the antis and the Hornbys. In Britain, explicitly oppositional supporter politics has led to the formation of several clubs, most notably AFC Wimbledon and FC United of Manchester. The former came into being in 2002 when a consortium purchased the original Wimbledon FC and moved them to Milton Keynes. Fans rallied and formed AFCW, an organisation with an unprecedently democratic ownership structure: they have risen swiftly through the semi-professional ranks to sit one division below MK Dons, the ‘franchise’ team. FC United, meanwhile, exist thanks to a section of Manchester United fans resentful at the increasing domination of top-level football by the market forces that have priced working-class Mancunians out of Old Trafford. The new, self-consciously socialist club attract crowds of between two and three thousand to their games in the seventh tier of the English football system, and have inspired similar projects hostile to football’s privatisation.

Beyond these cases, there is certainly an argument that club-level supporting is inherently politicised. Generally, the ownership of football clubs resembles a scale model of capitalism as defined by Marx: the supporters constitute the club’s identity, and thus create its ‘product’, but the entities which result are – almost universally – owned by a limited number of people with the financial wherewithal to purchase a stake. The football ‘experience’ is then sold back to the people who generate it in the first place, and the loyalty of fans allows for a monopolistic control over things like ticket prices. Barring the occasional confluences of interest that occur when proverbial local-boys-made-good take over their boyhood teams, the relationship between supporters and owners is effectively an antagonistic one.

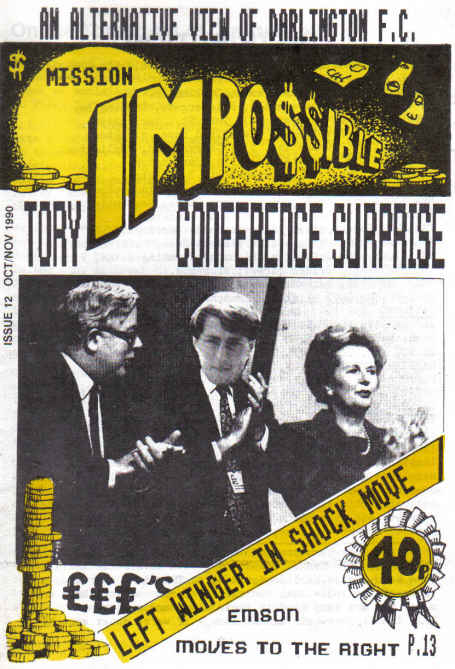

This antagonism is what lends supporting a team its countercultural force. In the 1980s, when the British game was in the process of encountering the first wave of rapacious asset-stripping Thatcherites, protest began to be expressed in the fanzine movement. Many football fanzine editors cut their teeth on DIY punk and post-punk publications and in the schismatised left politics of the late 70s and early 80s. At Darlington, my local club, the Xeroxed ‘zine was called Mission Impossible, and was sold outside our ramshackle stadium by bearded guys who fitted the visual archetype of SWP canvassers. It was dominated by extensively-researched investigations into the machinations of a series of disreputable chairmen, and also featured analyses of broader problems for supporters such as implementation of the Criminal Justice Bill at matches.

Like most fanzines, Mission Impossible complemented its political take on the game with discussions of leftfield film, music and stand-up, thus situating supporting within a more general context of popular dissent. The frame of reference for its coverage of music was based on the likes of Half Man Half Biscuit and, more intriguingly for a fourteen year-old from a farming town where Oasis and Shed Seven were considered sonic pathfinders, The Fall. The notion of a group who played aggressive, repetitive music overlaid with lyrics composed in a complex, cryptic spin on northern English was weirdly alluring, and seemed to echo the quickfire absurdism and surrealist wordplay – which would shock anyone who thought football was all gormless banter – I’d heard on the terraces. Ultimately, the experimental music I’d first encountered because of football developed into a love of modernist literature which has, well, ended up with me scraping a living in precarious teaching jobs and cultural journalism. To borrow Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher’s formulation to describe those bands who point towards a whole treasure-trove of obscure cultural expression, the invariably soaking South Terrace at Darlington was my ‘portal’.

Beyond this nostalgia, there are firmer links between football and experimental art. The standard rules of the game were codified in 1863, a year significant for aesthetics in that it was when Charles Baudelaire published the essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’. Baudelaire’s concern was to demonstrate that industrialised culture required new, more complex forms of representation, and aspects of his argument can be found in everything from Impressionist painting to noise music. The formalisation of football was also a response to the social shift away from traditional modes of living: in the games proffering of moments of extremely fleeting pleasure, it’s also possible to glimpse the French poet’s conviction that modernity could only offer transcendence in the transient. Few students of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century avant-gardes have investigated the link, but there’s a great book waiting to be written on the way in which football can claim to be a form of popular modernism.

So, if you’re frustrated by the myopic press coverage of Euro 2012, or you’re finding yourself bemused by the fact that football never seems to leave the television, it’s perhaps worth considering that the object of your indignation is not necessarily guilty of all it superficially appears to be. Beyond the jingoism generated by the national team and the hubris of the Premier League, football culture expresses itself with a creativity and spontaneity that the world at large seems unfortunately reluctant to acknowledge.