On announcing his retirement from directing, Béla Tarr, the poet laureate of slow cinema, told The Hollywood Reporter: "I don’t want to be a stupid filmmaker who is just repeating himself and dong the same shit just to bore the people."

The Turin Horse, the latest and presumably final picture in his illustrious oeuvre, is, rather fittingly, an apocalyptic tale of unrelenting nihilism, suggesting an unholy union of Miklós Jancsó, Antonioni and Beckett. In fact, the slow cinema tag seems a misnomer; if anything, this is drone cinema – bleak, harsh and ever uncompromising.

It took 146 minutes to watch The Turin Horse. It could just as easily have been a fortnight. Long-term Tarr collaborator Fred Kelemen shot the film in black and white and it is almost entirely shrouded in silence, bar interjections from a ferocious windstorm and the occasional philosophical revelation from a neighbour who calls round to replenish his bottle of brandy. But it’s not all glamour. Every scene (in fact, the film is comprised of a mere 30 shots) is infused, even drenched, with a relentless cloud of abject misery and expectant resignation. It makes Waiting For Godot seem like an episode of Teletubbies in comparison.

The movie is framed around the apocryphal story of Frederich Nietzsche’s descent into madness. As the opening narration relates, a 19th century cab driver began to violent whip his horse, borne of extreme frustration with the animal. Nietzsche happened to be passing by and was so incredibly moved by the scene, he embraced the horse in a vain attempt to protect it from the ceaseless punishment meted out by its owner. A neighbour witnessed the scene and brought Nietzsche home, who lay speechless on a couch for two days before uttering his ‘obligatory’ last words: "Mutter, ich bin dumm" ("Mother, I am dumb"). Nietzsche spent the remainder of his existence consumed with delirium. Tarr asks, not unreasonably, What of the horse?

Such contrarianism befits a director who has made a career out of creating vast, cinematic tableaux steeped in malleable relationships with time and space. This reached a peak with 1994’s seven-hour Sátántangó, the narrative structured into overlapping mosaic fragments – six steps forward, six steps back. Assuming he stays true to his word, Tarr will have retired from cinema at the relatively young age of 56, yet the ancient, primordial nature of his work suggests an archaic craftsman immersed in the prosaic raggedness of his environment.

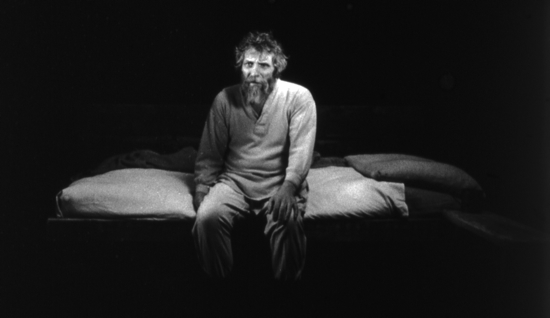

This raggedness is always to the fore here, especially once the viewer realises the Nietzschean prologue ultimately serves as tangential to the main action. The horse’s coachman (played by János Derzsi) arrives home – which seems like some inhospitable suburb of hell – to his daughter (Erika Bók), who helps him undress and prepares their food for the evening. This consists of one boiled potato each, a meal which is devoured with a grim intensity. Their situation is compounded by the horse’s gradual refusal to eat or work. We witness them repeat their daily routines throughout the following six days, enough time to ruminate on the active inner life while focusing on the seemingly impermeable veneer. It’s reflective of Tarr’s skill and poise as a filmmaker that such a monotonous daily routine manages to elicit so much dread and suspense amid the desolate yet beautiful aesthetic, one which the director has made his own since 1988’s Damnation.

Of course, it’s difficult not to examine The Turin Horse with an investigative eye, in an attempt to decipher the myriad cryptic allusions. However, it feels as if the film’s relentless drive towards a form of metaphysical apocalypse is simply a front for these sensitive portraits of the pair’s ostensibly insignificant yet utterly humane existence. The arrival of a troupe of feral gypsies, cursing the father and daughter to "drop dead", only serves to further emphasise the sheer struggle of routine which encapsulates their lives.

The nature of Tarr’s extended takes go so far as to morph the viewer’s physical relationship with the movie. Adapting to the pace of The Turin Horse can feel like a matter of recalibrating one’s biorhythms. But it’s a worthwhile adjustment. This remarkably weighty foundation doesn’t require an interpretative code to be enjoyed, and the film’s fascination ensures it doesn’t have to be read in this form in order for it to truly breathe and communicate with us. As a cinematic swansong, The Turin Horse is a formidable and fitting exercise in audacity. On its own merits, this is a frightening gaze into the void, with the void staring right back.