If those initial chopping and grinding chords that usher in Sugar’s Copper Blue didn’t make you sit up and notice that Bob Mould was about to make a quantum leap from the music that had made his reputation then arrival of bassist David Barbe and drummer Malcolm Travis several bars later sure as fuck did. The huge rhythmic push that thrusts the listener into the centre of this maelstrom is tempered by a layer of guitar harmonics that sign post the sense of menace and the inevitable end of a crumbling relationship at the heart of ‘The Act We Act’.

The sense of bitterness that opens the song – “I’m watching you walk/ As you walk that distant walk” – is palpable; in just a few words the scene is set and in a short space of time the soul is bared alongside the devastating juxtaposition of a sonic onslaught bearing sweet melodies. Here was power but here too was grace.

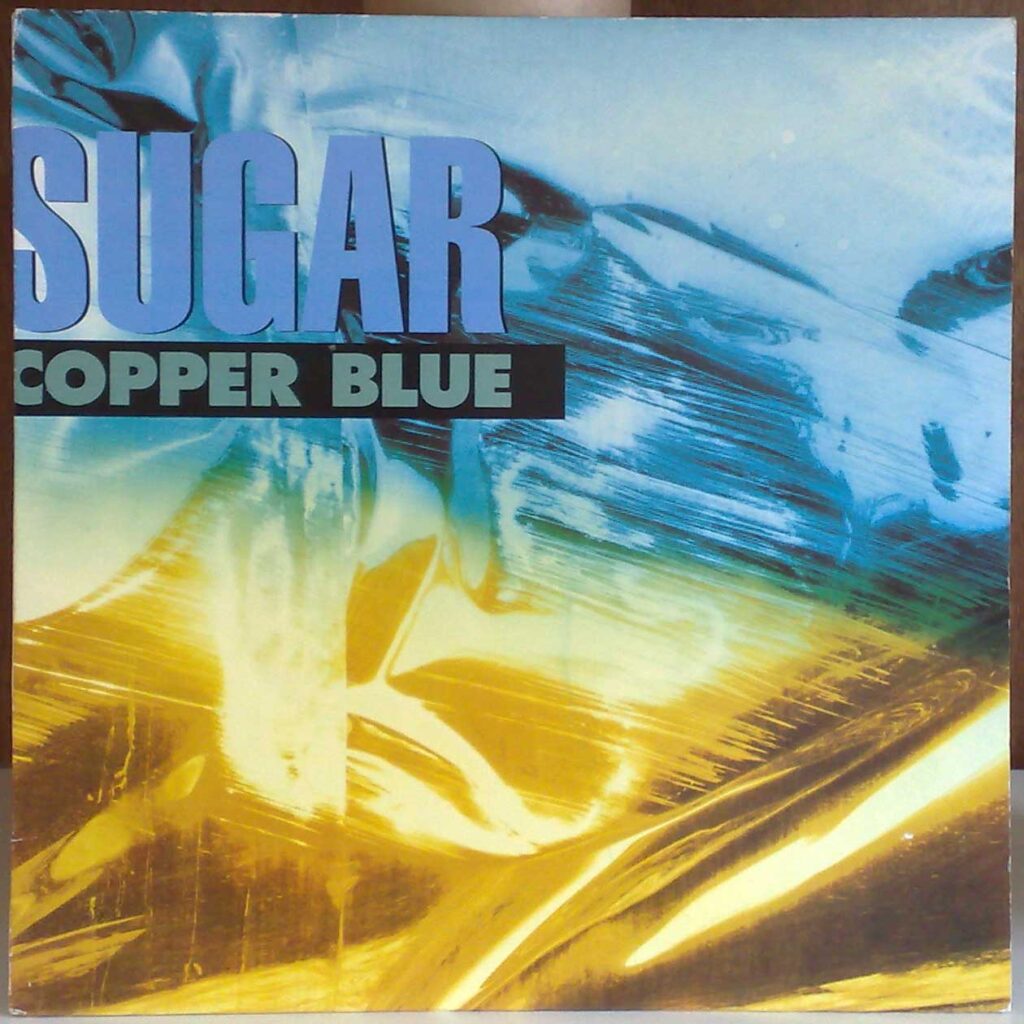

With the benefit of hindsight, Copper Blue’s arrival in the autumn of 1992 couldn’t have been better timed. The Pixies – a band who’d famously recruited Kim Deal via an ad that sought a bassist into “Hüsker Dü and Peter, Paul & Mary" – were busy imploding following the release of the disappointing Trompe Le Monde the previous year while Nirvana, formerly a minority concern from the Pacific north west, had achieved planet-shagging success on the back of Nevermind. And while a whole generation suddenly discovered the joys of melody, introspection and outright raw power, older voices were only too keen to point out the debt owed by these two bands and many other besides to the trail blazed by Bob Mould and his now defunct outfit, Hüsker Dü.

And what a trail that was. Though they finally burnt out in 1988 on a pyre of suicide, drug addiction and acrimony, Hüsker Dü was a band that broke away from its hardcore origins to move into more melodic and thoughtful territories whilst refusing to surrender their independence. A ferocious work ethic saw them release seven albums in six years – two of which were double. Even by the time they moved from the SST label to Warners, Hüsker Dü still self-produced resolutely uncompromising music. Despite the hopes of their new major label, Hüsker Dü failed to cross over to a mainstream audience but this was less a case of an aesthetic shortfall and more of a band ahead of its time.

1989’s Workbook and Black Sheets Of Rain from the following year found Mould taking an introspective turn. While the former found the singer-guitarist turning away from the bombast of his previous outfit, the latter saw Mound cranking up the amps and emitting a primal scream. Fine albums both but the experience would prove as emotionally draining for the listener as the man who created them.

Yet here was Mould now with a new band in tow and taking broader brush strokes then at any time in his career. Each of the ten songs contained on Copper Blue sees the band exploring new ways of playing with power and dynamics in a way that hadn’t hadn’t been considered before. The arpeggios that introduce the yearning at the heart of ‘Changes’ contrast beautifully with the noise that follows through afterwards while the chimes and grand sweeps of ‘Hoover Dam’ conjure up sweeping vistas and panoramas that simultaneously sum up feelings of cosmic insignificance and the need to belong to some kind of sense of security.

There’s humour, too. The grim murder at the centre of ‘A Good Idea’ is offset by a knowing musical nod to the Pixies, as if Mould is acknowledging the torch that was passed to them, then Nirvana and then back to him. Crucially, this is a band at work here. Though the songwriting responsibilities fall squarely on Mould’s shoulders – Copper Blue was culled from a batch of 30 songs and six of those were, in Mould’s words “quarantined” for its follow-up, Beaster – the playing of David Barbe and Malcolm Travis underpins and grounds the activities around them. From the off, Travis’ huge drums are at stark odds with Grant Hart’s percussive contribution to Hüsker Dü while Barbe’s solid bass locks in with Travis to build the performances’ solid foundations. His descending lines on ‘Helpless’ add to the sense of confusion at the root of the song as the groove locks in murderously.

At the centre of it all was ‘The Slim’, Mould’s response to the AIDS epidemic that had cast its long and grim shadow over the preceding decade. Mould had yet to fully embrace his sexuality and the song was written from an observational rather than experiential point of view but here was confrontation, acceptance and fear as Mould laments, “When you left with your death/ I felt empty when I looked back/ On my pillow/ What you used to say… I’m left behind." Brave and bold, it also tackled head on what so many wished would simply go away.

Looking back at the other strong albums it beat to nab NME’s Album of the Year in 1992 – REM’s Automatic For The People, Spiritualized’s Lazer Guided Melodies and P.J. Harvey’s Dry among many others – it becomes obvious that Copper Blue is the most mature of the lot. Great albums all, but Copper Blue is the experienced older brother, the one you can trust and rely on above all others; it offers insight, joy, pain and so much more in its running time. A reclamation of sorts, Sugar’s debut album saw Bob Mould emerge from the shadows reserved for trailblazers to becoming the star he’d always deserved to be. It’s easy to forget just big Sugar were. Copper Blue entered the UK album chart at number nine and in a very short space of time found themselves elevated from ULU’s sweaty environs to the impressive setting of the Brixton Academy.

Revisiting Copper Blue is to find an album that hasn’t dated in the slightest. It deals with the kind of universal truths that aren’t time bound and its animalistic sonic power remains undiminished. Indeed, listening to the newly re-mastered version of this masterpiece is to be introduced to even more strength and energy than one had expected. Ultimately, Copper Blue is an album that not only sounds as good now as it did twenty years ago, but also one that’ll still blow cobwebs away two decades hence.

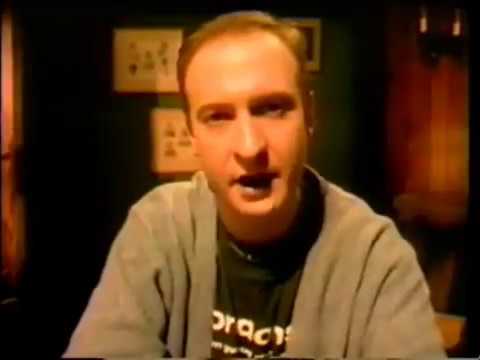

You released two solo albums after the demise of Hüsker Dü in the shape of Workbook and Black Sheets Of Rain. What made you decide to return to a band format and how did Sugar form?

Bob Mould: I guess it all started in 1990 when I was wrapping up the tour for Black Sheets Of Rain. I’d been a solo artist for two records and I had great rhythm section with [drummer] Anton Fier who’d played with The Feelies and The Golden Paleminos and he was very gifted player and I’d learned a lot from him. Tony Maimone was on bass and he was another original Cleveland musician and he was huge influence on me playing in such great bands. I had a great rhythm section but for me it was getting to be financially hard to keep the show on the road. I let those guys go and early in ’91 I let my management company go after finding out some weird shenanigans had been going on that I wasn’t aware of and ended up costing me a lot of money.

So in the spring of ’91, the only thing that I really had was the ability to go out and play solo acoustic shows. I set out for about nine months of solid touring doing that and going around America. I was living in Brooklyn at the time so I’d rent a car and drive around the East Coast playing acoustic shows every night. I was writing a lot of new material so I’d go out and play these new songs and try them out in front of people and I was able to gauge what was working and what wasn’t. It was really a lot of fun doing that.

I remember coming to Europe in the summer of ’91 and I was on a lot of shows opening for Dinosaur Jr where people would yell at me to get off. It was the crusties and it was a little weird! I was also getting out to a lot of festivals with Sonic Youth and Nirvana and sometimes having to play between them, which with the 12-string was something of a challenge!

Anyway, the upshot was that I spent nine months writing new material and playing all these shows and in the fall of ’91 I was targeting record companies trying to get a deal and it turned out that Alan McGee was the first person who was honestly and truly receptive to the idea. Meeting at the Creation offices was really great and I was gathering things for what was supposed to be my first solo record. I knew a couple of musicians that I knew would make for a great rhythm section – I knew [bassist] David Barbe through a lot of mutual friends in Athens, GA, and he had just finished up his band called Mercyland. I reached out to David and played him some demos and he was really excited at the prospect. The other musician was Malcolm Travis who was the drummer with a band called The Zulus and I’d produced a record for them in 1988. Malcolm was great guy and a really good drummer and The Zulus had just wrapped up so he was available.

We all got together in late January or early February of 1992 and spent three weeks rehearsing in the Athens, GA, for these nebulous recording sessions. It wasn’t a band at that point but what made it a band was before we were ready to leave Athens and head to Massachusetts to record these songs, Barrie Greene who was a booker at the 40 Watt club in Athens asked us to fill a last minute vacancy and play and show and we were like, “Oh sure. Why not?” And that was the moment we were like, “Ooops! What are we going to call this?” So the three of us and my then-partner – who was on the management side of things – were eating at a waffle house and there was pack of sugar on the table and that’s how it all happened!

Can you remember the moment when the three of you first played to together and it all clicked?

BM: I had sent those guys fairly elaborate home demos and the first day of rehearsal we worked through the first three songs [‘The Act We Act’, ‘A Good Idea’ and ‘Changes’] in order I knew it was going to work at that point. Right away it clicked. The recording sessions were a lot more difficult than the rehearsals. We had 30 songs to work on and we didn’t play as unit; we constructed things in pieces. The real eye-opener was the first rehearsal because the first three songs sounded so good.

Copper Blue arrived after Pixies last album, Trompe Le Monde, and Nirvana were straddling the world with Nevermind. Both bands owed a huge debt to Hüsker Dü so did it feel like coming round full circle for you?

BM: Yeah. The stage was set for Copper Blue to be a successful record. It’s a really great record. I sort of got lucky with the song writing and the timing because there are so many great records that don’t get noticed for years. It was funny because back in 1989 there was a stretch of shows where I opened up for the Pixies on the West Coast of America and then there were the festivals with Nirvana in ’91 and in between I’d also been considered as producer for what became Nevermind. So it really wasn’t a case of, “Oh my God! Who’s this cashing in on these guys!”

We all had this common history. But I’ll tell you what – when I heard Loveless in late ’91 I was simply blown away. I thought I had a great bunch of songs to go into the studio with but when I heard that record I was like, “Uh, oh! I’ve really got to step it up here!” It really was a kick in the pants. There really hasn’t been anything like it.

Copper Blue is a far more powerful and muscular album than anything you’d done before.

BM: I think I grew into that. Hüsker Dü was like a very, very fast jet plane that never really touched down and it didn’t have a lot of grounding to it and that was the beauty of that sound. I think playing with Anton taught me the value of grounding and how to actually build the foundation for a song and how to stay steady and see it through and make it move from the bottom up. I think that’s where I picked that up and that naturally folded into Sugar material. The Copper Blue material was little less frantic than the Hüsker Dü stuff. It’s much more power-pop. And the production was much intricate than any Hüsker Dü production and it’s a finely crafted record.

I also had the luxury of time with Copper Blue and I also had that with Black Sheets Of Rain which was a three-month process. I had learned not to accept the first take. I love the first take if it’s great but [co-producer] Lou Giordano and I really had an objective to really tighten the record up, make it seamless and really spend time on the details. This was my third record as the singular songwriting force so I’d grown more comfortable in that role. All those lessons and all those experiences came together in one place and I think that’s key in the success and longevity of that record.

One of the standouts on Copper Blue is ‘The Slim’ which is an incredibly brave thing to write. Was that drawn from personal experience and did you feel a responsibility to tackle the subject?

BM: It was pretty visceral. ‘The Slim’ is was what AIDS was called before it was called AIDS. The song is fictional and based on the experience of so many other people. At the time, I didn’t fully understand those ten years of grief. I saw it but I walked through it. I wasn’t touched by it as much as other people that I knew and especially people that I’ve come to know since who have lost dozens and dozens and dozens of people. I was writing from a sort of visceral, accidental and naïve spot and it wasn’t informed by years of experience; it was just observation and feelings.

As far as responsibility goes, no; I didn’t write it to be anything other then an emotional song that just happened.

You were outed several years later in a magazine feature but one of the interesting aspects of Copper Blue is that the lyrics are very gender and sexuality neutral. Was this a deliberate move on your part to say that these emotional tales that you’re taking us through are universal truths regardless of gender and sexuality?

BM: Yes, it was intentional and wasn’t only that which you stated which was very accurate. There’s also the part in my autobiography where I talk about it and the self-hating homosexual that resided inside of me and having trouble with the notion that a song might be a gay song and therefore excluding a large percentage of the audience. I really wanted it to be accessible to everyone on an emotional level. It was also, for better or worse, my idea of what gay music was. Years later I knew much better but at the time I wasn’t comfortable being a spokesperson or being put in a category that I didn’t really identify with. And years later I look back at people like Tom Robinson or Jimmy Somerville who really had to do the heavy lifting and even before them you’d have Sylvester who had a different approach to them. There were people that were so attuned to the gay identity and the gay experience and they were very comfortable wearing that badge. I didn’t have experience in that community so it was strange to me at the time. I didn’t have an active connection and I certainly didn’t have a gay identity. The only identity I had was ‘Bob Mould: Punk rock musician’ and that was the identity that defined me at the time.

I don’t know if you can remember the video to ‘If I Can’t Change Your Mind’ but there was another sort of ‘tell’ in that. At the end I’m holding up a series of Polaroids as the song goes through the chorus and there’s one that I hold up of me and my then-partner and I turn it over and it says, “This is not your parents’ world” and that whole video touched on the idea of relationships and love. There were same-sex couples, there were heterosexual couples with children, there were teenagers with grandparents so the video was very telling.

I don’t know if I was building up to coming out. I was just building up to the next tour!

You said that you didn’t want to be a spokesperson for anyone and that’s something that comes through on ‘J.C. Auto’ on Beaster which was recorded during the same sessions as Copper Blue. Was that what you were trying to say on that album?

BM: Beaster was recorded at the same time as Copper Blue. Out of those 30 songs that I mentioned earlier, Beaster was six of those songs and they got quarantined pretty quickly. I recognised that they were a dark suite and I felt that as I was writing them in ’91. I remember one specific night at the recording studio when it all became clear to me and yeah, that was a patch of really dark songs.

I went to church as a kid and my mom was very religious but I wasn’t brought up strict Catholic and neither was I raised in a religious household. I went to Sunday school and went through confirmation and all that stuff and it’s always been a bit of a battle for me and Workbook had a lot of that imagery. With Beaster, that came about after a phone call with my partner and I don’t really remember specifically what it was that set me off but I had one of those internal tirades that just started going into the notebooks. That’s when the whole thing really tied together. I guess it’s a just a crazy rant at the end of the day! I don’t want to minimalize it but that’s how that stuff works. It’s not like I’m going to sit down and write this blood-letting opus.

You mentioned earlier that Alan McGee and Creation were the first label to express interest in Sugar. How familiar where you with the label and its pedigree?

BM: Not as much as I would become familiar. In the fall of ’91 I’d been round some companies in the US. I used to go in with a DAT machine with a handful of songs but I wasn’t really getting a great response. But I had a friend who worked at a record company and she knew I was ready to go to England and suggested that I go and meet with Alan.

As soon as I met Alan, I knew that he loved music; it was very clear and his whole life is music. We’d sit around and talk about music and he made it clear to me the impession that Hüsker Dü had made on a lot of the music that he’d worked on.

The odd part was – and to tie it back to what I knew about Creation – when I was living in Minnesota in 1988 me and a couple of friends had a very small record label, a singles-only label. We released 7” singles by obscure bands and we put out a Moby single before he got big. I remember getting a demo tape in late ’88 from a band in England who at the time were called Shake Appeal and one of the songs was called ‘Son Of Mustang Ford’ and they were going, “Oh, we’re thinking of changing our name to Swervedriver.” I think the world of those guys and it all made sense. Life is funny but it does steer us to the place where we’re all supposed to be.

Copper Blue was voted NME’s Album Of The Year in 1992…

BM: I couldn’t believe it! I was the 17-year-old kid who used to take the 45-minute bus ride to the record store in the middle of winter in Minnesota and I would sit on the radiator and read NME, Melody Maker and Sounds cover to cover so I could work out how best to spend my $8 on five import singles so I understood the gravity of it.

You’re about to take it on the road again. How does Copper Blue look to you from a distance of 20 years?

BM: It’s a fucking party is what it is! I love those songs, I love that record and I love playing those songs. They’re fun to play. ‘The Slim’ is taxing and you have to be careful with that one. I’ve done a couple of these shows already in San Francisco and it was really great. I thought we sounded really great and even though it’s not Sugar those songs sound really familiar. It was great to look out and see how people were connecting with it but 20 years is years. The last time I looked out playing those songs then people were going ape-shit crazy and jumping off the PA and now 20 years later I’m going, “Why is no one jumping off the PA? Oh! Right! Got it…” So once I managed those expectations it’s been going really great.

Sugar’s Copper Blue and File Under Easy Listening have been reissued by Edsel. Bob Mould and band play Copper Blue in full at Shepherd’s Bush Empire on Friday June 1