It’s no understatement to say that Alien 3 was poorly received on its theatrical release and, with 20 years hindsight, it’s not difficult to see why. Alien, released in 1979 and famously directed by Ridley Scott, changed the landscape for hard science fiction movies. Scott would further redefine the vision of a dark, corporate future a few years later with Blade Runner, but contemporary thinking discarded the Philip K Dick-inspired masterpiece and, generally, Alien was seen at the time as a masterfully crafted haunted house movie. Its impact on the horror scene was widely felt and fully acknowledged, but the finer details and its broader impact upon science fiction as a whole would continue to resonate with audiences, writers and filmmakers for years to come.

A sequel was inevitable and, when it arrived seven years later, it would be an altogether different beast. It seems ironic looking back that the dark tone of Scott’s original – the reason for its unique feel – would be jettisoned in favour of the apparently more crowd-pleasing 1980s action staples of machine guns and explosions. In James Cameron’s Aliens the threat from HR Giger’s beautifully realised and nightmarishly sensuous bio-mechanoid is reduced to that of a hive of insects, suggesting that if one well-armed grunt with a bit of American know-how had been aboard the Nostromo there never would have been a franchise in the first place. In order to inject some drama, tension is introduced in the form of incompetence and greed on the part of the human characters.

It’s not in the least surprising that Aliens is so thematically inconsistent with Scott’s film. James Cameron had no interest in following a lead. He wanted nothing more than to make his pet project, Starship Troopers, even making the novel mandatory reading for the cast. Hence the constant references to drops, bugs, bug hunts, xenomorphs and countless other thinly veiled references to Robert A Heinlein’s tale of heavily armed soldiers travelling from world to world in hyper-sleep and utilising a combination of infantry weaponry and tactical thermonuclear devices to pacify trouble spots. The Stars & Stripes-decorated United States Colonial Marines and their constant references to bug hunting, not to mention the ‘Bug Stomper’ motif on the side of the drop ship, plainly punctuate Cameron’s utter contempt for maintaining any sense of continuity with Alien‘s nationless, corporate future.

Sadly the role of the Alien itself, its classic design features altered by Cameron to make them look more insect-like, is reduced to that of an opposing, numerous and expendable form of disposable infantry akin to the bugs in Heinlein’s novel. The ultimate peril is not the terrifying otherness of the unknown, but the damaged cooling system of a nuclear reactor, caused not by the conflict between humanity and a life form utterly extrinsic to our own, but by stray bullets from the marines themselves. Despite every effort on the part of the filmmakers to portray them as finely honed military machines, the heroes essentially come off as a gang of idiotic yahoos.

Nevertheless Aliens was phenomenally successful and, as an action-adventure movie, it moved the art forward several steps in terms of pacing and sheer excitement. All the more surprising then that the owners of the franchise at Brandywine Productions chose to take such a bold and deliberate step in dismantling Cameron’s carefully constructed model for further sequels that many assumed would not only endure, but define the Alien franchise for years to come. The ’80s comic book spin-offs almost exclusively took Cameron’s Aliens as their cue for expanding the universe and inevitably annexed the Predator concepts (thanks to a throwaway set dressing joke in Predator 2). Inevitably when Alien 3 was released, and the realisation dawned on a majority of the hardcore fanbase that the landscape had changed radically, there was a tremendous fan and critic backlash.

Alien 3 had a difficult genesis. Producers Walter Hill and David Giler courted numerous young gun writers and directors such as Renny Harlin, Joss Whedon, William Gibson, David Twohy and, most famously, Vincent Ward in their pursuit of a new angle for the franchise. Ward’s vision in particular came closest to fruition and the details of his incredible script and design ideas have been well-documented. Sadly that tale of a monastic order living inside an artificial wooden planet filled with cathedrals and wheat fields is now one of the great what ifs of cinema. That said, it is likely that if the producers had pursued that version all the way then it would have been extremely interesting, probably brilliant, but an absolute commercial failure. Even by 1992 it is doubtful that cinema audiences were quite prepared for a mentaloid Name Of The Rose in space involving nightmarish, Hieronymus Bosch-like imagery that included sheep with human faces where their arseholes should be.

After getting cold feet about Ward’s script, Giler and Hill backpedalled to a David Twohy draft (much of which would be developed further for Alien: Resurrection) and combined the most basic elements of Ward’s ideas with Twohy’s space prison concept. 1992 was a good year for the space prison movie, with Stuart Gordon’s riotously stupid and entertaining Christopher Lambert vehicle Fortress also hitting cinemas. The two films bear little comparison however. From the outset the visual style and flair of first-time director David Fincher elevate Alien 3 to a level seldom seen at that point in genre fare and generally isolated to the works of Ridley Scott himself. Sadly for Fincher his ‘noob’ status was exploited mercilessly by the studio. His time on the movie was characterised by perpetual interference from numerous on-set producers, disingenuous ‘production assistants’ reporting behind his back to head office, daily script rewrites, surly cast and crew members objecting to both the rewrites and his meticulous perfectionism, and the ignominy of being removed from the editing process. This ensured that the final product, although beautiful to look at, wasn’t entirely cohesive.

What it did have was a great design aesthetic and a phenomenal core cast. Aliens fans had a bitter pill to swallow when its surrogate family never made it past the opening titles alive. Instead of the dashing Corporal Hicks, Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley finally gets a love interest in the form of Clemens (Charles Dance), a morphine-addicted medical officer with a track record of severe malpractice. Her ‘best buddy’ analogue switches from the pure and innocent android Bishop to Dillon (Charles S Dutton), spiritual leader of the small community of prisoners and, by his own admission, "murderer and rapist of women". Finally, and perhaps most shockingly, the angelic child Newt is disposed of (and autopsied) to be replaced by a mob of personality disordered, hygienically challenged convicts with a tenuous and newly found faith in Christ. This was a particularly difficult decision for many to take on board: James Cameron described it as a personal betrayal and "slap in the face" to all fans of Aliens, while novelization writer Alan Dean Foster labelled the story decision "an obscenity".

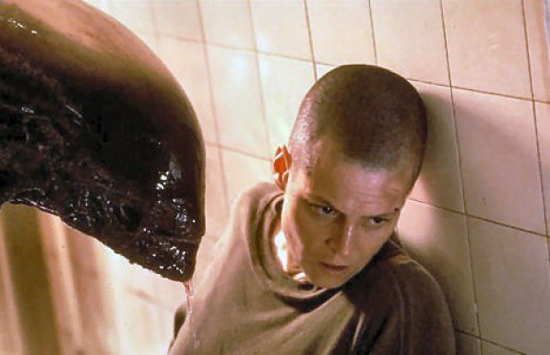

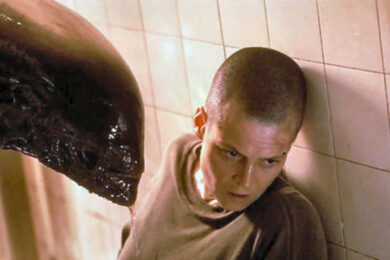

It is often the case with great drama that a difficult gestation and birth period results in more intense on-screen performances and unpredictably vivid results. Throughout Alien 3 the players convey palpable angst and tension that is entirely credible based upon their dark, brooding environment and fraught interactions with each other. When the beastie does emerge it has reverted to its original look with a few Giger-inspired twists, no longer resembles a humanoid insect, and is suitably terrifying. The cast have little difficulty selling its menace. They do have some trouble selling the overall narrative but that is neither their, nor Fincher’s fault.

The theatrical version of Alien 3 released in 1992 was a hastily hacked, re-hacked and reshot version of Fincher’s cut. While one reshoot in particular had tremendous power (the dog ‘birth’ scene) the overall result was damaging. It seems a normal tactic with studios that when they misunderstand or just plain dislike a product they simply chop it down in length and make it faster-paced. It rarely works. Fortunately a more complete cut has been available for some years and the recent Blu-ray release has corrected the audio faults on earlier DVD transfers. The difference is phenomenal. Few films have ever benefited so greatly from this kind of ‘director’s cut’ treatment: the transformation of Alien 3 is on a par with Terry Gilliam’s sublime, full-length version of Brazil.

Alien 3 was purported at the time to be Paul McGann’s big Hollywood break, but his role in the theatrical cut was so reduced as to be almost meaningless. Here his deranged prisoner Golic is fully restored. Brian Glover’s Superintendent Andrews, while still evidently an officious prick, has room to take on a level of humanity denied him in the shorter cut. The remainder of the cast also have more time to develop and assume separate characteristics. Best of all the extra half hour of running time allows more opportunities to admire the look and feel of what is a magnificent slice of violent sci-fi monster madness. There are still a few warts here and there. Some early computer generated enhancements contrast starkly with the first rate practical effects – and one of the corporate troopers at the end is obviously wearing cricket pads – but on the whole the extended Special Edition cut of Alien 3 is one of the best realised and most convincing futuristic movies ever made, and a worthy successor in tone and spirit to Scott’s original.

Ultimately the greatest strengths of Alien 3 are encapsulated in its total rejection of the popcorn-friendly, roller coaster approach and nuclear family motif of Cameron’s red, white and blue Starship Troopers pastiche. Instead it restores consistency with Ridley Scott’s nation-free, hard-tech industrial corporate future that we are about to see again in Prometheus, with no Stars & Stripes or machine gun porn in sight. Alien 3 is intentionally uncomfortable and, flying in the face of rational thought, it eschews all of the essential trappings of commercially successful science fiction to deliver a grim, nihilistic tale of cockroach-ridden redemption utterly unburdened by the lightweight trappings imposed on the genre by Star Wars, and later repackaged in camouflage by James Cameron. That’s why it is a great film and that’s why so many people hate it. To those people I say, Chin up. Avatar 2 is coming.