The towering and shining canyons of New York City may, at first glance, appear to be the unlikeliest of launch pads for the exploratory and cosmos-straddling journey to the centre of the universe that is space rock. This, after all, is the city that creates its own rhythms on the streets – a combination of millions of chattering voices, the screech of police sirens, the honking of cars and the pounding of feet against the avenues and streets that criss-cross that can range from the skittering patterns of Jimmy Cobb to the paranoid, face-chewing beats of Maureen Tucker.

Yet from The Velvet Underground to Sonic Youth and all points in between, The Big Apple’s relationship with driving amplified music has always been fertile and so it proves with White Hills. Perhaps it’s exactly those street rhythms and the occasionally claustrophobic nature of New York that creates a desire to simply blast off and head into the stars? White Hills seem to think so.

Having enjoyed the patronage of no less an authority of all things kosmische than Julian Cope, White Hills – based around the core duo of guitarist Dave W. and rock-solid keeper of the low-end rumble, Ego Sensation – are set to the return the UK as they unleash the latest in a long line of releases in the shape of new album, Frying On This Rock.

“We’re about to head off to the cold just as it’s starting to get nice here!” laughs Dave W., thinking about his imminent trip to the UK, as The Quietus hooks up with the pair via Skype. Perhaps so, but given White Hills’ ability to melt brains and blow minds in a way Timothy Leary would have approved of, the last thing anyone’s going to be thinking of is the weather.

Frying On The Rock has a greater live feel than H-P1. Was this a deliberate move?

Dave W: We basically do the same thing when we get into the studio; it’s pretty much live. But the difference between the two is sonic clarity. We did H-P1 at Oneida’s space – and the three records before that were also done there – and this new one was done with Martin Bisi and Martin’s been recording bands for about 30 years and has 30 years of experience and I think that the sonic quality of the recording is much better. I think that the dynamic range of the sonic quality maybe translates that sense of liveness or sense of urgency.

When we were mastering the record we were listening to H-P1 and the new one and listening to them side by side and the dynamic range is drastically different. I think that had a lot to do with recording it with Martin in his space and how he goes about recording with the kind of equipment that he has and especially the microphones.

We didn’t want to make H-P1 again and doing records that closely together can be a bit tricky. When we did that album we had a synthesiser player play with us live in the studio, which doesn’t happen that often. The majority of the time the synth parts are put on afterwards so there was a whole aspect of the music that was playing off of the fact that we had someone playing with us live.

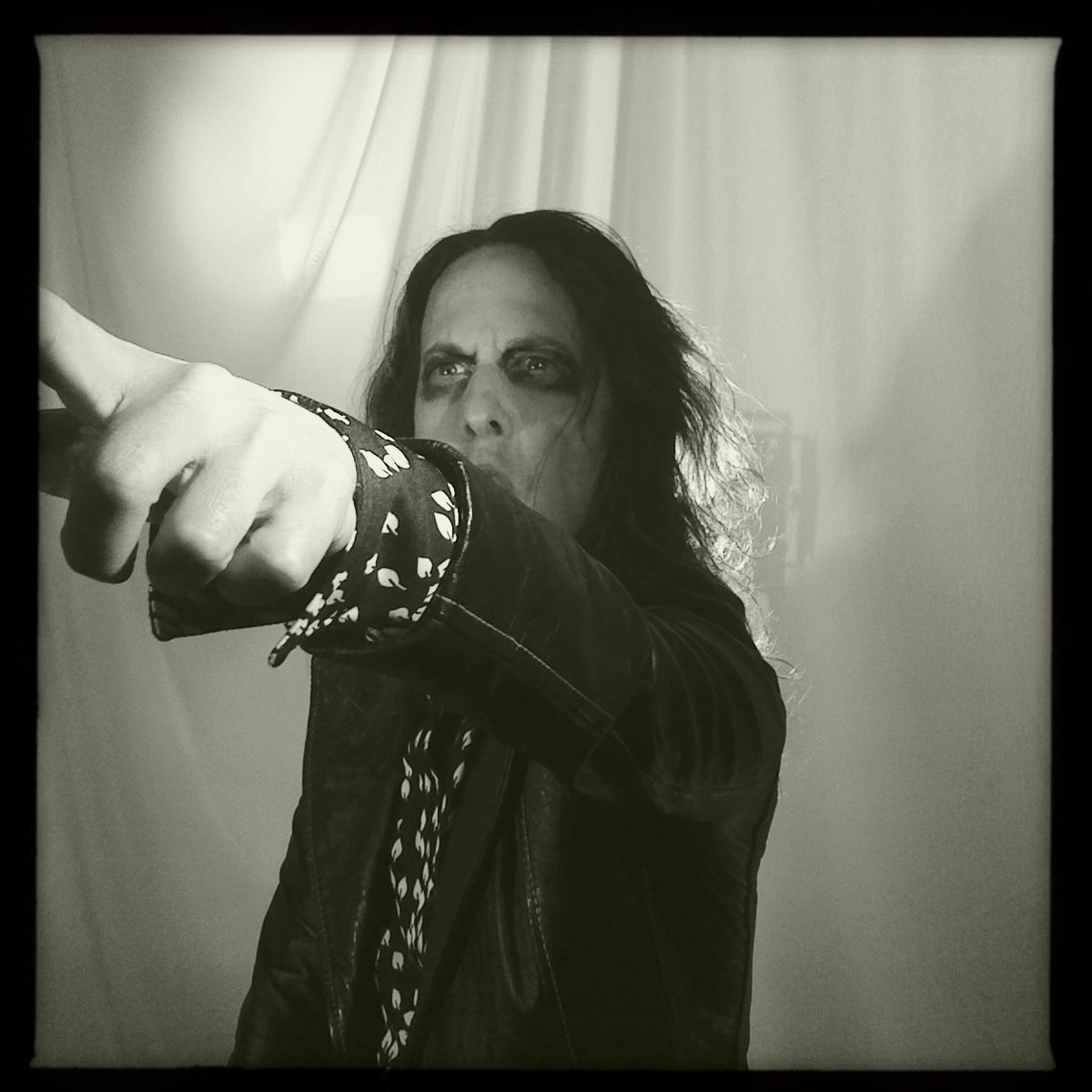

Interview continues after picture

Having been a one-time resident of Manhattan I can confirm that it’s the least psychedelically inclined city I’ve ever visited. Is your music a reaction against or to your surroundings?

Ego Sensation: I guess it’s a reaction to and against our surroundings. I mean, to me, New York City is pretty psychedelic. There have to be about 30 things I see a day that are just mind-blowing! Absolutely mind-blowing! People talking to themselves, people having conversations on the phone where they have the little ear plugs in and they’re saying the craziest things that make no sense and just seeing people and how they conduct themselves on streets. It’s a very inspiring place. It’s sensory overload all the time.

DW: Yeah, and what we do musically is sensory overload. It’s pretty intense and it’s pretty in your face as is the city.

But do you not find that the music you’re making is contradictory to your urban surroundings?

DW: Yeah, I think it is and I do think it is a reaction to it. People are so concerned with a sense of consumerism that you don’t get elsewhere and I think that the music, as much as it is pounding, is there to open your mind and to allow yourself to get lost.

It’s funny what you say about consumerism. I was on the Bowery last year and couldn’t believe how much it had changed. There was a store near the old CBGBs site that was selling rock & roll memorabilia for around $400 a go…

ES: Yes, exactly. And there’s a Starbucks that has just opened in the East Village! Just last week we were walking by and we were like, “Oh no!” It’s finally oozed its way in. There’s a 7-11 opening on The Bowery. There’s a lot of that kind of thing. And you’re bombarded by pop music everywhere as well. I used to live in San Francisco and I was never familiar with new pop music because I never listen to mainstream pop music but in New York you have no idea how but you know these songs! It’s like everywhere you go and every store you go into or every bar and they’re all playing the same songs.

DW: I think it’s very removed from what it means to be a human.

As you say, consumerism is everywhere. Is the space rock that you make a form of escapism from that or does it have something to say about the environment in which it’s created?

DW: Well, I think with some of it, it could be escapism. I mean that playing the music allows me to escape at times but also there’s always been with this band very much a statement in reaction to the things that we see, whether that be societal based or politically based or whatever. We’re not telling anybody how to live but we’re offering insights into what we see.

ES: I also feel that it’s music as art as opposed to pop music that is a commodity that’s sold on the basis of “This is what you should dance to; this is going to be a hit.” It’s an art form and people need art.

DW: Yeah, it’s heavy music even if you’re escaping. Within it it’s like you can escape in a way that can’t escape in the sense of when you watch a television programme or when you watch a movie. It’s mind-expanding and hopefully it makes people think in some way.

Given the extended nature of some of your music, do you view it as a blank canvas where the listener can paint their own interpretation on it or is there something specific that you’re trying to achieve?

DW: It’s definitely a blank canvas that people can paint whatever they want onto it. Everyone comes with a different set of standards…

ES: And different people focus in on different aspects of the music. It’s always fascinating reading different reviews and some of the things people focus on in the music we’re sometimes surprised to hear. The great thing about music is that it’s so subjective.

DW: It’s personal. When you can get someone to associate something personal with what you’re doing it becomes more ingrained with the listener and it then becomes something that the listener owns. What we do is part of a greater thing that’s been happening for years. We’re just part of this huge song and it’s great that people can find something within it that they can hold.

Interview continues after picture

As mentioned, you’re noted for some epic pieces of music. How much discipline is involved in that or is it more a case of taking off on a journey and seeing it where it takes you??

DW: [Laughing] No discipline! With the longer pieces I think they all have their natural points of ending.

ES: It’s a magical thing as typically it’s just the three of us playing together and there seems to be this synchronicity where everybody kind of finishes at the same time.

DW: When you’re making music like that you’re not always on. Everybody’s not always together within. When you get those moments when you are together within it then it just naturally has its progression. That’s very magical because it will do what it does. It’s like a form of language and whatever collective of musicians are there then it is like a form of vernacular.

ES: It does take time from when you start a piece to finding out what the other people are doing and locking in with them and then you expand upon it. There comes a point when you get to an area and it’s like travelling; you find a great rest stop and it has an espresso machine and you can hang out there and have a good time. And then, of course, you have to move on and then find another spot. It’s like a journey.

White Hills is a band that releases a huge amount of music across a variety of formats. What’s your quality control filter?

ES: You know, we record a lot [laughs]!

DW: Yeah, there’s stuff we’ve got from years gone past that we still haven’t listened to. I like to put out something special for every tour that we do. I used to do one thing specific for every tour but over the last few years it’s been one thing that we’ll stretch though the various tours that we do. So we have this new thing: we have the third instalment in the Oddity series where we have this poster sleeve and we have these various recordings from rehearsals that have never seen the light of day. I haven’t listened to them for a long time and when I started putting them together certain things hit me. From there it was a simple editing process so I think it’s a case of what feels right at a particular moment.

There seems to be more of a European sensibility to your music than any American roots. Do you find yourself gazing across the Atlantic more for inspiration?

DW: When I kind of really got into music it was all about British music for me. I was always reading the British rags and seeing who was new and what was out and buying any import I could gobble up. When I was very young I had a friend who had some older brothers and that was the first time I heard Motorhead and Sex Pistols and that was like nothing I’d heard before that. As a young kid I was all about San Francisco hippy bands but the biggest record that gave me my first proper mindfuck as a kid was P.I.L.’s Metal Box and that really set me off on the tangent. I then got into Juju-era Siouxsie And The Banshees and Bauhaus and that whole kinda thing. Then I got into bands like The Telescopes and Thee Hypnotics, Loop, Spacemen 3 and that whole era. I was gobbling up everything that I could.

But also being reared on stuff like Jefferson Airplane I still always had the greatest fondness for guitar music and guitar solos so it wasn’t too difficult to get into The Bevis Frond.

You have something of a revolving door policy when it comes to drummers and other musicians. Do you worry that this might make for a lack of consistency in your sound?

ES: I think we’ve had amazing luck with drummers – our current drummer Nick Name is great – and it has only helped us grow more.

DW: I think that the great thing about it is that everyone does have their own flavour. So even though it’s within the same idiom there’s something about it that’s different. And also, with the older stuff that we continue to play it breathes in new life and it causes us to think about playing things differently. The biggest thing about playing with new people is just finding someone who can grow with you. Can that person be involved in your unit to take it to the next level?

What’s the biggest misconception about White Hills?

DW: [Laughs] That we’re from Brooklyn! And that we’re a metal band or a stoner rock band. But it’s all personal; if someone sees us as a metal band then that doesn’t really bother me, per se.

What’s the last thing you learned?

ES: The last valuable thing that I learned is that you really do have to speak to people in their own language. You speak to someone in English and you realise that even then no two people speak the same language. When you’re speaking to someone they’re hearing it through their own filter and sometimes you have to think about who that person is and how can I speak to them so that they can understand.

White Hills play the Lexington for The Quietus this Saturday, March 24th supported by Arabrot. You can buy tickets here