“In Australia, we don’t have the same tradition that Messiaen or other European composers have for using birdsong as inspiration. All our birds are harsh, unforgiving and angry sounding. It’s the same for insects, like cicadas and crickets at night. They’re really electronic, for one thing, and all of that has contributed to how I think about sound.”

I’m with sound artist and curator Lawrence English in the century-old Queenslander home he shares with his wife, Bec, in suburban Brisbane. Outside, the chatter of lorikeets, blue-faced honeyeaters and noisy miners forms an audio backdrop that contrasts with the local passing traffic. Inside, the couple, along with their black Schnauzer, Nacht, are adapting to a new arrival, their three-month old daughter. It’s here that English assembles his sonic compositions and runs his sound art record label, Room40, “delivering sound parcels from the Antipodes since the turn of the century”.

Before starting Room40, English played in local industrial bands, worked as a tour manager and was a music journalist. However, one of his most poignant and preparatory influences came as a boy, while birdwatching and searching for reed warblers with his ophthalmologist father. “Dad would say, ‘Close your eyes and listen for the bird. When you get a sense of where it is, open your eyes and look for it’,” he recalls. “That was my first experience of thinking about sound and space, how you can have certain objects that activate a given space.”

He now makes solo sound work that incorporates and is shaped by field recordings – a passion that has taken him from the Amazon to the Antarctic, continually searching for new perspectives. His interest in sound, English explains, stems from it being ‘non-representational’. “Rather than being prescriptive – like with cinema or photography, where you’re looking at an object that in a way is set – with sound, once it’s removed from its source, you invite interpretation,” he says. “For example, if I play the sounds of wind at a concert, I know those winds are 70 miles an hour in Patagonia and I was having great difficulty recording and standing up. For someone else it’s ‘Like that time we were in Cornwall and there was that storm’, or ‘Like when I was a little kid and we were at the beach’. Everyone brings their own social baggage. That’s what interests me about sound.”

Using his recordings as building blocks, which he often distorts and further refines within the studio, English explores, “the relationships that bigger plates of sounds might have. When you slide them against each other, particularly live, the relationship changes the way that I hear the work. With rhythmical concerts, there’s this ‘train track’. You could change the pace but you’re still on the track. What I like about textural work is that it’s like an ocean. You can sometimes be riding on the top of a wave, or in the valley between two waves, or sometimes you’re drowning. You kind of move in a liquid way, rather than in this very set [way].”

Having collaborated in 2002 with British sound pioneers David Toop and Scanner (Robin Rimbaud) as I/O3, English views 2004’s self-released album Ghost Towns as his “first really serious concrete piece”. From there, the basis for much of his solo work has involved field recordings that provide a thematic core, while pursuing a specific concept. “I’m not one of these people who thinks, ‘I’m going to make an album’, and it just kind of happens,” he says. “I have to have a frame.”

The resulting process has seen solo releases from English arrive annually, including his seasonal series, which began in 2007 with the chilly and desolate For Varying Degrees of Winter. That album was followed in 2009 by A Colour for Autumn, an equally sparing affair, though one pricked with signs of life where its predecessor buried them.

“The joke is [that] Vivaldi’s had it for too long and I’m breaking into the territory!” he laughs of his seasonally themed albums. “The next one is summer, which is called Where There’s Light, There’s Shadow. So rather than making a ‘summery’ album – because as much as I like the Beach Boys, I can’t match them for summer! – I thought, the one consistent element of summer is shadow. Everywhere in the world, Antarctica, England, here: ‘where there’s light, there’s shadow’. That’s basically the thing for the record. I’ve just started to work on that now.”

English applied a similar approach with 2008’s Touch-released Kiri No Oto, within which he sought to transcribe “visual fog into an auditory effect”. While its Japanese title translates as the ‘sound of fog’, its actual inspiration arrived during a train journey between Berlin and Krakow. “I was sitting in the cabin looking out the window and as we came into Katowice this really heavy fog set in, which was also probably smoke from the town as it was really cold,” he remembers. “As we pulled up, I was thinking to myself, ‘Wow, that’s really dense fog!’ and I realised if I focused on one element, like the spire of the church, I could make it out as a discrete element. However, the moment I tried to bring that out of context and put it in a wider perceptive, it was lost into this wall of fog. So I was curious [about how] when you have a large wall of sound, if you focus on one element, you can make out that [it’s] making the melody or a particular harmonic or pulse. But the moment you try to bring it back into relief, you get this overpowering wash of blur.

“Then, there’s also this idea of harmonic distortion,” he continues. “When you have one element and another together, they work for and against each other. There are these moments of relief and sometimes you get this moment of blurring, like the fog. That is the crux of what I’m on about. It’s about that relationship.”

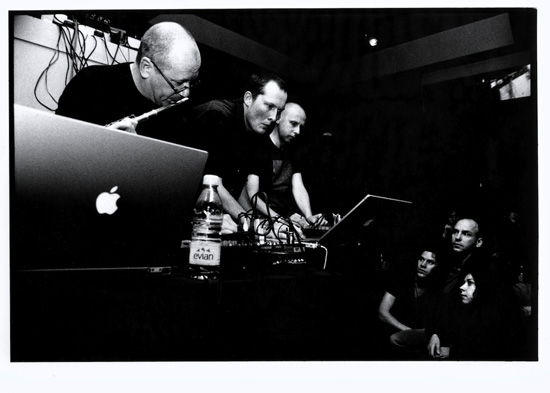

I/O3 – Lawrence English with David Toop & Scanner, London, 2004

English’s latest recording, The Peregrine, released last year on Experimedia, is similarly grounded by a strong theme. Given his early ornithology experiences, you might expect this album to reference the behaviour, flight and predatory skills of its eponymous bird of prey. That however, is only part of the story, as English’s actual inspiration was J. A. Baker’s 1967 book of the same name. Published as an anonymous diary between October and April during an unspecified year, the book condenses Baker’s decade-long study of the peregrines that wintered near his Essex home.

“I have to say,” English confesses, “I still am really obsessed with The Peregrine as a book”. Having first encountered Baker’s prose in 2008 when visiting Toop in London, it profoundly affected him and his work. “Initially,” he says, “it was the way Baker talked about sounds that would otherwise not be particularly interesting, but the way he situated them was just so eloquent and imaginative. What I really like was how he could encapsulate these sweeping landscapes but at the same time pay attention to the dew on the grass, and marry those two things in a really natural way. I thought that was an interesting idea to try and play with. To have detailed stuff that’s within the pieces, but also within these white, landscape-sized chunks of sound.”

Even without knowing its title, Even without knowing its title, musically The Peregrine’s searing, high-pitched tones and disharmonic drones suggest a timeless experience of soaring and infinite landscapes. However, English’s version is a homage to the book which he says, “drove the project entirely. The text was the compositional guide. I could almost feel the music in the words, and that for me, hasn’t really happened before. It was a very active choice not to have any field recordings. Rather than go to East Anglia and make my impression of the landscape, I wanted to bring it back to what inspired it, and use that book as a backdrop for the project entirely. Each chapter, each part of the diary, is one of the pieces, and I picked particular passages that epitomise the experience of reading the book. That December entry – ‘Frost’s Bitter Grip’ – that section still haunts me to this day! It’s such an intense description of finding this particular circumstance and then dealing with it.”

December 24th – The day hardened in the easterly gale, like a flawless crystal… Near the brook a heron lay in frozen stubble. Its wings were stuck to the ground by frost, and the mandibles of its bill were frozen together. Its eyes were open and living, the rest of it was dead. All was dead but the fear of man…

No pain, no death, is more terrible to a wild creature than its fear of man… We are the killers. We stink of death. We carry it with us. It sticks to us like frost…

I feel compelled to lie down in this numbing density of silence, to companion and comfort the dying in these cold depths at the foot of the solstice:… those whose blood now courses from the hunting frost, whose frail hearts choke in the clawed frost’s bitter grip.

— J. A. Baker – The Peregrine

Within an album already heavy with heightened tension, English’s audio interpretation of the above passage creates a sense of time suspended, where the listener is starkly aware of their surroundings and yet subject to a greater, external force. A situation where the observant hunter becomes suddenly conscious of their own inevitable annihilation – an experience that Baker likely felt himself whilst observing and writing at a time when faced with his own illness and in the midst of the Cold War.

On Baker and his book, English remarks that “the thing is, you never know anything about him. That’s what’s so fascinating. You don’t know where he lives, what he does, how he eats – anything like that. It’s almost like you’re literally tearing out his eyes and using them to look at the land, tearing up all his senses and experiencing this place through his lens. Basically, he wants to become the bird, becoming progressively more obsessive and a little bit misanthropic, anti-humanist. There is no real role for the human in this land and when there is, it’s almost as the undead. It’s an unwelcome addition to the landscape. That really grips me, this tension between himself and other people. Particularly because there was this thought that the peregrine falcon population would become extinct. So there’s a political element to it, where there is a kind of awakening happening, and the birth of the whole ecological movement was linked to books like this.”

Previously, when considering English’s sound art within sunny Australia, I wondered how he viewed his work within a seemingly apolitical world. Modernised, manicured Australia can often appear idyllic and untouched by global concerns. Even after being struck by disaster, Brisbane now shows little sign of last year’s floods that washed through the city and were cleared within a week by volunteers. That, though, would be to overlook ‘the Lucky Country’s’ high cost of living that excludes many – especially its original people, marginalised after the continent was colonised by the nation with whom English shares his name.

English himself admits to pitching himself outside his native country with most of his work coming from Europe and Japan. “From the outset, when Room40 started, I decided to focus on entirely international possibilities,” he says. “Australia is great, with lots of possibilities and great things you can do, but it’s not possible to sustain a practice like this. It’s just too young a country with too small a population and not enough [artistic] centres.”

For English that has meant continually maintaining different streams, which in addition to his solo work include numerous collaborations, as well as publishing, concerts and curating sound exhibitions with Room40. In this way and through the internet, he has overcome the ‘tyranny of distance’ that previously characterised Australia’s colonial history. “In all honesty, I’m a product of my times,” he admits. “The way I work is because of things like a laptop that I can take on tour and perform and use as an instrument. I’m sure I could do it other ways, but it’s profoundly changed the opportunities for someone like me.”

This also works both ways, as the concerts and tours he organises for visitors have, he says, “given us a great opportunity to bring people here, from New Zealand to Japan to all over. That building up of a network between people in other countries and here, bringing them together… I’m a great believer in this global community network thing.” Given that 70 years ago (and within both our fathers’ lifetimes) Australians feared being invaded by Japan, English’s collaborations with Japanese artists like Tenniscoats is not insignificant.

Additionally, English has been developing a project closer to home called Site-Listening, which involves “attentive listening in any chosen location, privileging the auditory environment as the focus of attention”. Taking in natural, urban and industrial sites within Brisbane and across Queensland, English has profiled dozens of locations with personal descriptions and recommendations on times of day for interested sound explorers to visit. Recalling his last road trip, English can even enthuse about the absence of sound, as found in spartan areas west of Brisbane. “There was this amazing hushed awe,” he says. “This audible silence that felt like a pressure all the time. Things like wind in the small trees, because of the flatness of the land, you could hear this for miles on either side. It felt like the land breathing. I haven’t found that in other places that I’ve been to.”

As well as encouraging a person’s awareness of their environment, I ask about the wider impact from such observations. English replies, “I was just talking about this with Chris Watson, the guy that does a lot of recordings for David Attenborough [and was formerly a member of Cabaret Voltaire]. He was citing research in the Netherlands, but there’s similar research here in Cairns [northeast Queensland] on a couple of species of birds next to highways that have raised the pitch of their voice to be above the noisefloor of the road, so they can communicate with each other and breed. Other birds have disappeared from regions because they can no longer effectively communicate, and they either move or die out.

“That’s a fairly common phenomena,” he continues. “Small birds need particular kinds of habitats that aren’t really catered for in the suburbs and cities. One example is a small bird called the silver eye. Where we lived on the other side of town, the recordings I made ten years ago, I could hear them in every single recording. Now I hear one or two a week. Generally I don’t see them anymore but I see them out west, in areas where there is more habitat for them and they’ve got better options.”

For ten years I followed the peregrine. I was possessed by it. It was a grail to me. Now it has gone. The long pursuit is over. Few peregrines are left, there will be fewer, they may not survive. Many die on their backs, clutching insanely at the sky in their last convulsions, withered and burnt away by the filthy, insidious pollen of farm chemicals. Before it is too late, I have tried to recapture the extraordinary beauty of this bird and to convey the wonder of the land he lived in, a land to me as profuse and glorious as Africa. It is a dying world, like Mars, but glowing still.

— J. A. Baker – The Peregrine

Within the UK and since Baker’s book, peregrine numbers have also changed – though rather than nearing extinction, there are now over 1400 breeding pairs. Restrictions on the use of DDT, combined with a worldwide recovery programme, have shown that some human initiatives can be of benefit to nature. Meanwhile, nearly fifty years apart, on opposite sides of the globe and through different mediums, an obscure English nature writer and a modern Australian sound artist share a common purpose: to raise their own species’ awareness of its innate sensory abilities, and to appreciate the majesty and fragility of nature.

More on Lawrence English and his projects can be found at his website, as well as the Room40 site. You can buy his releases at the Room40 store. For more on English’s Site Listening project, visit the Site Listening website.

Photos: Greg Neate / www.neatephotos.com