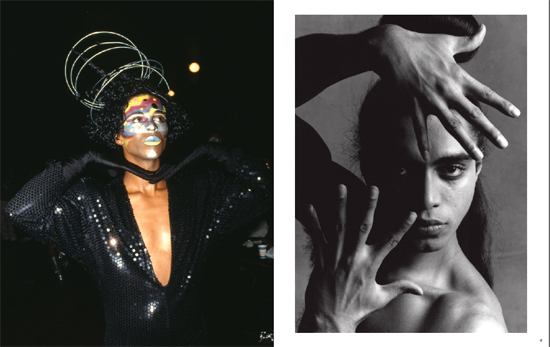

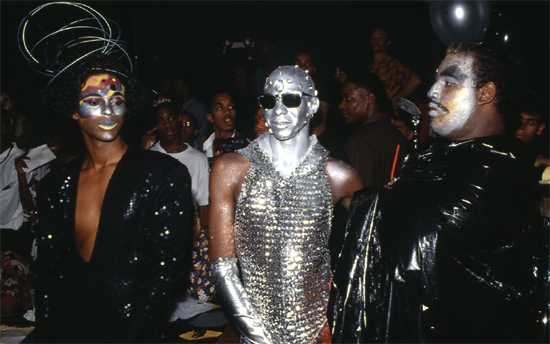

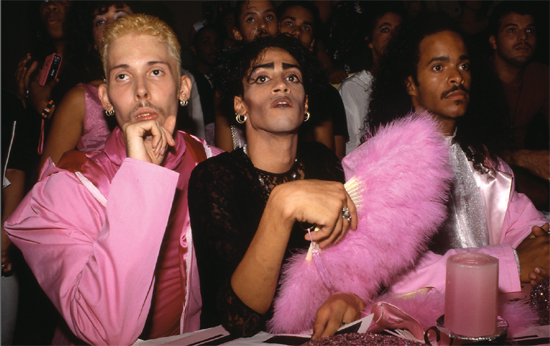

A beautiful and insightful new book from photographer Chantal Regnault, Voguing And The House Ballroom Scene Of New York City 1989-92 reveals New York’s ballroom and vogue scene of the late 80s and early 90s in all its fabulous glory. While both Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ and Jenny Livingstone’s more discerning film Paris Is Burning shone a light on this underground culture, it’s only really now with Regnault’s book that this bastion of gay black and Latino culture is getting the coverage it deserves.

The history of drag balls in New York can be traced back to the 1930s where Harlem venues like Elks Lodge and Rockland Palace hosted decedent and extravagant parties. These "Spectacles in Color", as Langston Hughes termed them, were a vital yet largely forgotten part of the Harlem Renaissance, where divergence from the American norm was celebrated through the arts. If the early balls were diverse, they were also very much white owned. This changed in the sixties, when Harlem’s gay black community staged its own events. It wasn’t until the following decade though that the ‘Houses’ that supported the balls became formalized. "In 1977 an imperious, elegant queen named Crystal LaBeija announced that a ball she’d helped put together was being given by the House of LaBeija, as in House of Chanel or House of Dior," explained Michael Cunningham in his essay ‘The Slap Of Love’.

Tim Lawrence’s liner notes to the Soul Jazz book provide a useful insight as to why these Houses were needed. "Black, gay, working class drag queens found themselves estranged not only from their biological families, which were usually intolerant of their choices, but also the ruling cadre of black nationalist leaders, whose increasingly macho ‘real man’ discourse was popularised by the gangs that multiplied on the streets. With nowhere to turn, they formed their own self supporting gangs, which they preferred to call Houses."

These Houses became even more important with the rising spectre of AIDS in the early ’80s. Through the devastation that followed, the history of one of America’s most incredible art forms was largely lost, along with the many originators who have sadly passed on. Some dance historians argue that voguing came to fruition behind the prison walls of Riker’s Island, but most agree that it has its roots in the ballroom category of presentation, as well as throwing shade or reading.

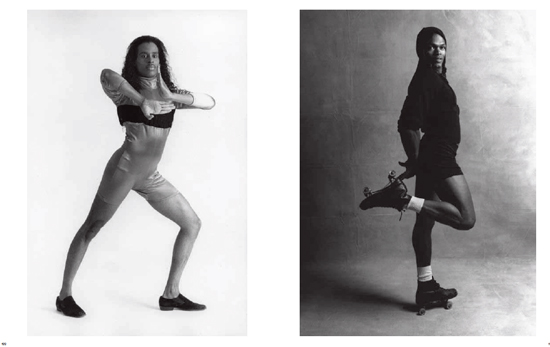

"Reading is the real artform of insult," explained Venus Xtravaganza in Paris Is Burning. "You get in a smart crack, and everyone laughs and ki-kis because you found a flaw and exaggerated it then you’ve got a good read going on… Vogueing is the same thing. Taking two knives and cutting each other up, but in a dance form." This artistic competition born out of adversity draws comparisons with the early days of b-boy culture in the South Bronx, as Robbie Saint Laurent tells Regnault: "I think voguing was probably a gay version of breakdancing in a way. But it was only done pretty much in private. When it was in a club setting, it was more like a duel, people dancing with one another to see who can dance the best."

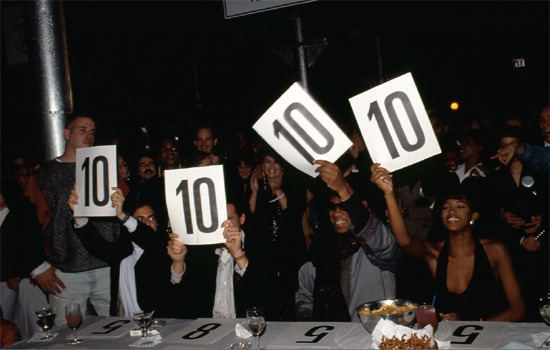

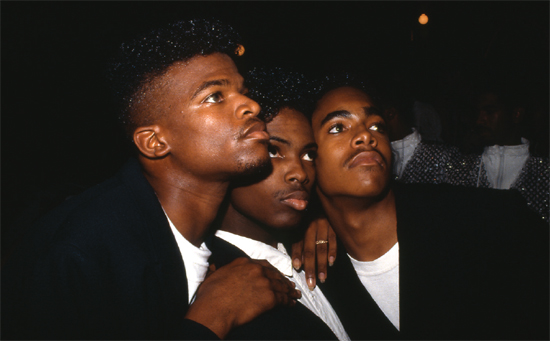

The clubs provided an important platform for the ball community during the period covered in this book, as we see from the many photographs taken at Tracks. While both Better Days and the Paradise Garage became important hang outs for the ball children in the late seventies, it was a Tuesday night session at the Chelsea club Tracks where voguing really exploded onto the dancefloor. "There were constant battles," the club’s DJ David De Pino told Tim Lawrence. "It was like [a] Yankees-Mets game."

As DJ Danny Krivit told me in an interview a few years ago, there were particular records that brought out the fiercest moves in the voguers: "The music had a certain edge to it, a specific chopping edge that leant itself to the moves." In one of the many revealing interviews in the Soul Jazz book voguer Muhammad Omni explains the deep musical connections. "Voguing is an African American dance, made for and by African-American people [and] the music is very important. It is modern progressions of the African drum. It is the ethnological musical imprint that comes from blues, jazz, gospel and funk. All these things were embodied in the traditional music of vogue." As he goes on to explain MFSBs ‘Love Is The Message’ became the theme song of the scene because "the jazz breaks fluctuated so much you could find a lot of moves to do off that song". Other (pre 1990) ‘Old Way’ anthems that had the edge and mood described by both Muhammad and Krivit included ‘Ooh, I Love It (Love Break) (Shep Pettibone Mix)’ by the Salsoul Orchestra and ‘Love Thang’ by First Choice.

By the early ’90s the arrival of ‘New Way’ vogue styles, characterised by their more dramatic and angular moves, demanded music to match. The club where these new sounds erupted was The Sound Factory (also the backdrop to some great photos here), where DJ Junior Vasquez span fierce and raw tailor-made ballroom tracks like ‘Walk For Me’ by Robbie Tronco and ‘Feel This’ by Robbie Rivera. (‘Walk For Me’, interestingly, has emerged again on UK dancefloors in the last eighteen months, in the form of Joy Orbison and Boddika’s ‘Swims’, which samples its eponymous vocal motif.) One of the most informative online vogue sources, the House of Diabolique, explain the ‘New Way’ soundtrack perfectly: "These are more than just bitchy songs; they form a soundtrack of power, control, manipulation, escape and fantasy. They glorify gayness and femininity."

This would also be a perfect description of the photography of Chantal Regnault, who has provided a unique and informative study of this incredible period in New York’s cultural history. Through both colour and black and white photography taken at clubs and ballrooms across the City, Regnault captures the scene wonderfully. At the same time, the interviews provide a personal insight into why the scene became so important for so many. "Survivors from the late 1980s tell me how addictive the ball scene was, and how some of the children ended up just living for it. Or dying," the photographer laments in the introduction. And while many of those featured in the book were cut down by the cruellest of diseases, these pictures and the accompanying interviews provide a fitting and very moving tribute to one of black America’s most vital art forms.