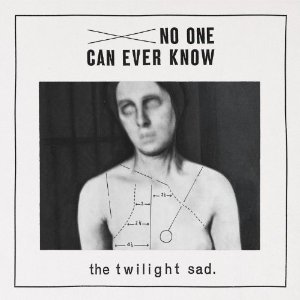

If shoegaze was a wordless reaction to indie’s verbose ways, The Twilight Sad’s brand of ’emo-gaze’ has been two fingers to the miserablism that’s defined Scottish indie for years. Not that The Twilight Sad are anything other than depressing shits, but they frame their provincial fatigue in a kind of profuse majesty, pushing the band towards the realms of magical realism. No One Can Ever Know, however, marks a new direction for the Lanarkshire natives. Name-checking a host of frigid art-rock bands, they’ve replaced the wall-of-sound guitars with icy synths and, we’re told, the stark stylings of Keith Levene and Magazine’s John McGeough. Andrew Weatherall, meanwhile, was brought in to achieve a "colder, sparser sound". Alas though, the Scots seem unable to fully part ways with the gushy extravagance that made them, obstructing the path to something more radical. On ‘Another Bed’, singer James Graham’s "I’ll find you – don’t worry" is a gesture of cold, threatening malevolence, but the music is all Daniel Day Lewis, grimacing with overblown passion in a waterfall.

The transition from heart-on-sleeve shoegazers to post-punk nihilists is hampered by half-measures and uncertainty. What with the warm swathes of feedback shipped for more brittle fare – ever so slightly draining the Scots’ sound of its humanity – this is by far their bleakest record. But their nerve must have faltered somewhere midway to Joy Division’s beautiful severity. Rather than chillingly abstract, the sound presents a very earthly misery, more evocative of a shit day at work than the unknowable void that is the human condition. Add to that a less epic, more lowly pitch (pomp is not the modern way), and the outcome is a play for ‘otherworldly’ which, ironically, sooner recalls the drabness depicted by Moffat and Middleton, but without their wit.

To get to the bare bones of it, these songs carry too much weight to be austere (‘Don’t Look At Me’ is one such offender), or are too dense to nail that hauntingly stark mindscape the Scots are aiming for (‘Dead City’ is a woolly mess). The bass assumes the role of good ‘ole metronomic melody aid, U2-style, as opposed to the tension machine of post punk renown, while the electronica – ranging from skittish pulses to analogue synths – is window dressing rather than the starting point for reinvention. ‘Sick’, for example, is basically a turgid Idlewild with Suicide’s drum machine. Neither are the various bleeps and synth-lines deployed discriminatingly enough to be penetrating, with ‘Another Bed’ dampening its Mitteleuropa trappings with over-arrangement.

All in all, No One Can Ever Know occupies a muddled, frowsy no man’s land, leaving the impression of another in a long line of essentially stodgy indie-rockers with designs on European artsiness (stand up The Editors). Not only that but, no longer the lush prospect of before, the Scots newfound brittleness serves to detract from what’s traditionally been their best quality – the sumptuousness of their sorrow. Formerly in service to Graham’s grandiose woes, the shapeless structures and the singer’s through-composed vocals aren’t as stirring without the effluent shoegaze context. It works both ways, though, with the numb, petrified mood of ‘Not Sleeping’ sabotaged by Graham’s burning histrionics.

That said, at times it’s an intriguing record, containing isolated moments of exhilaration. The most forthright track here, closer ‘Kill It In The Morning’ glows with ghoulish panic, while the stunning ‘Nil’ – employing oil-drum beats and a Kraftwerkian arpeggio – builds from unease, to the suggestion of impending doom ("There’s only one way this is going to end") to vastation. Elsewhere, the electric-macabre ‘Alphabet’ features the most dread-inducing synth sound in recent memory (reused for ‘Nil’) while ‘Another Bed’ challenges Cold Cave in the field of theatrical synthwave.

If somehow they had devised a sonic twin to the toxic sense of shame underpinning Graham’s voice, the result, you suspect, would’ve been the corrosive artistic statement they seek, and a startling synth record. But with too much compromise, and a sound that amounts to ‘feeling like shit with a synth-y twist’, this is a timid stand for a band who’ve made a career out of courageously embracing their fears.