Time is a funny old thing. As a fluid entity, various altered states can speed it up, slow it down, or suspend its very notion altogether. The thirteenth edition of Berlin’s Club Transmediale might carry the theme ‘Spectral’, but its most interesting events are those that deal quite specifically with time itself. Whether consciously or not (the latter is certainly often the case), several performances and installations over the course of its week-long tenure play with time as others might an instrument. The resulting seven days play, for us, like a locked groove. Festivals always fly by in an instant, but this year’s CTM doesn’t so much walk us through its week-long tenure as chew us up and spit us out. We’re welcomed back to the concrete-encrusted delights of Luton airport in what feels like the blink of an eye.

In that sense, CTM mirrors – or certainly couldn’t be more perfectly suited to – the location of the majority of its venues, Kreuzberg, an area where it’s easy to exist in something of a bubble. And Berlin itself tugs at a Londoner’s sense of what an urban space ought to look like. The first thing it’s impossible to ignore is just how much space there is here, a contrast to the packed streets of the Big Smoke, where flocks of property developing gannets swiftly descend upon every free plot, hungry for an easy feed. Even quite near the city’s centre, its wide streets occasionally open out onto vista-type views. The bridge over Warschauer Strasse S-Bahn station, near where we’re staying, is a good example, the railway avenues that run beneath carving long lines of sight through the city skyline. Add that to a large amount of unused post-industrial space and the attractively bleak, flat-fronted East Berlin buildings nearby, the bitter cold at night and regular dustings of snow (the cold weather, I’m assured by a local friend, is a recent arrival), and it all adds up to the sense of having escaped to some alternate reality. Or at least, it does for someone used to overcrowded pavements, winding little roads and sweaty, elbows-first aggro on public transport.

For a first-time visitor and house/techno lover, the ultimate physical manifestation of that bubble is probably the Berghain, an imposing breezeblock of a building that squats in a patch of unused land peppered with gnarls of tough grass. According to the mythology surrounding the club – its strict door policy, hedonistic atmosphere, the undulating intensity of its signature sound – it’s a space within which it’s possible to throw off the normative shackles of time. That does indeed prove to be the case – though more on that later. Recently it’s been opening its doors to a far wider array of music than the pummeling, brutalist techno it’s become known for, and over the course of the week CTM host several events within its cavernous surrounds.

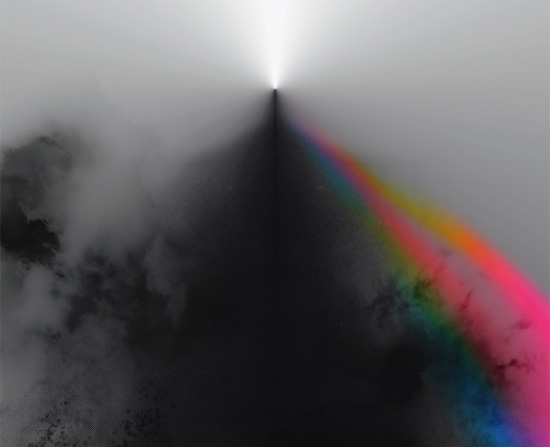

Contrary to popular rumour, initial arrival inside the ex-power station is met not with addled euphoria and astonishment, but rather a vague, ‘Ah, so this is what it looks like in here’. Admittedly, that’s probably to do with our first Berghain experience occurring on a Tuesday night at the brain-friendly hour of 10pm, for a near-overwhelming sub-bass workout from Sendai, a new audiovisual collaboration between Peter Van Hoesen and Yves De May. The usual club-friendly momentum of Van Hoesen’s techno work largely absent, here in the resonance chamber of the Berghain their focus is on depth and force, vaguely danceable broken rhythms pockmarked by bursts of sub so physically present that they press like hot breath into the back of the neck. The greyscale visuals onscreen above the duo’s set-up, meanwhile, glower down at the crowd – one segment finds the screen carved down its centre by a thin but impenetrably dense hairline fracture, like a crack ripped open between this world and the next.

While this slightly downbeat introduction to such an infamous venue does diminish its initial impact – barring the sheer size of the place, and the soundsystem’s ability to create such punchy dynamics in a boomy environment – it’s nice to slowly uncover each extra facet of the space. Great iron-framed windows tower above the main dancefloor proper, dividing it from the bar next door. Swing benches hang, naughtily, on chains from the ceiling of the bar. Battered old lockers, doors held on at jaunty angles, act as reminders that people used to work here in an entirely non-leisure capacity.

Only brief reminders though: on Friday evening the place hums with an entirely different energy. Not Equal have taken over the Berghain space, hosting the likes of Ben Frost, Roly Porter and Ancient Methods, while upstairs in Panoramabar the Perlon label is holding court for the night. It’s at this point that the place’s time-stretching properties become fully evident. Morphosis further abstracts the phantom techno of last year’s What Have We Learned? album into the realms of dark, cracked ambient, and teases a crowd desperate for the relief of a beat with fragments of percussion and super slow, heartbeat rhythms. By the early hours when we’re ensconced in Panoramabar, flitting from benches to dancefloor to bar and back again, house’s steady pulse is playing tricks with time, and it’s increasingly tough to determine the hour. Ancient Methods’ set later still, back downstairs, is all molten fury, their techno licked with flame and the resounding crash of heavy machinery. In this context, even more so than usual, the duo’s chosen name feels prescient, tapping into a very base-level, instinctive energy where fight or flight are the only possible responses (at this point it’s worth pointing out that for most of my companions flight is the more appealing of the two, most vanishing swiftly into the safehouse upstairs). We follow later. It’s near 8am when we make an exit, but it could be any time.

Grouper’s Circular Veil performance

Her music couldn’t be more different, but Grouper’s Circular Veil show the following evening, experienced still woozy from the preceding night’s excesses, play similar tricks with perception. Liz Harris and collaborator Jefre Cantu-Ledsema’s seven hour performance/installation (it convincingly blurs the lines between the two) is designed to mirror one full sleep cycle. With the theatre auditorium dark save for the very slow revolution of murky visuals, Harris and Ledsema sit in the centre while the audience radiate outward, lying prone on the floor, on pillows or propped against walls, beer in hand. We manage to spend nearly three hours there, which slip by in a half-asleep heartbeat, lulled by warm, distorted tape loops. Just pared back enough to be unobtrusive, but involving enough to remain interesting, they flicker around the edges of perception in a pleasantly jarring way. Our only regret is not being able to stay for the whole thing, thanks to missing the beginning and end due to other performances.

Which arrives neatly at how easy it proves to puncture the festival bubble. The challenge facing a city festival such as CTM or Krakow’s Unsound, which it most resembles, is to create a convincing suspension of outside reality. Unsound, for example, is a precious experience because its mood stays unbroken for its entire week’s length, bolstered by very clever organisation that ensures festivalgoers can – if they wish – attend almost every concert and discussion group. For all its beautiful presentation and excellent programme, CTM, a sister event to the longer-running Transmediale digital art and media festival, falls slightly short in this department. Unused time during the days, especially in the early part of the week, could potentially be filled to avoid some of the more debilitating clashes that marr the festival’s second half. Often, during the run from Thursday to Saturday, two or three equally excellent musical events clash so completely that it’s impossible to make the dash from one venue to another. Clashes are, to a certain extent, inevitable at any festival, but with an entire week to play with it’s a shame that the weekend’s scheduling doesn’t quite do justice to the uniform excellence of its content. Especially for companions who’ve bought a ticket for the entire event (plus Transmediale’s entire programme) it’s quite a sticking point, and makes it difficult to feel like you’re fully engaging with an actual festival, rather than just a series of standalone events.

It’s testament to the strength of what we do see that it’s possible to repeatedly plunge back into the vortex. Saturday night post-Grouper, Hieroglyphic Being uses tricks of tempo to turn Horst Krzbg into a disorienting blur for the senses. Jamal Moss’ own musical output and that of his label Mathematics has a hot-headed unpredictability, drawing equally from percussive Chicago jack tracks, disco and post-punk. His DJing mines the same space with similar impunity, and does so in a way as to both confound and delight dancers – a mid-set appearance of Talking Heads’ ‘I Zimbra’ is a revelation, colliding head on with a house beat for a festival of off-kilter polyrhythms.

Moss’ mixing is scattershot, beats regularly slipping out of sync with one another, lending his set’s baseline groove a slightly uneven, gloopy feel, like it’s being played straight off a sun-warped 12". Most interesting, though, is his total disregard for dance music’s usual notions of tempo consistency – he regularly cuts one track straight into the next mid-bar, dropping instantly from brisk house clip to slow disco rumble. He also plays his decks’ pitch-faders like extra instruments, often slurring tempos down by 8% and distending tracks outward into grotesque versions of themselves. The whole experience is exhausting to keep up with, the consistent jolting shifts in energy leaving only devoted dancers on the floor. But it’s also hugely exciting to move to, and brings to mind some aural version of Dali’s melted watches, bending notions of time around a sweaty 6am club crowd.

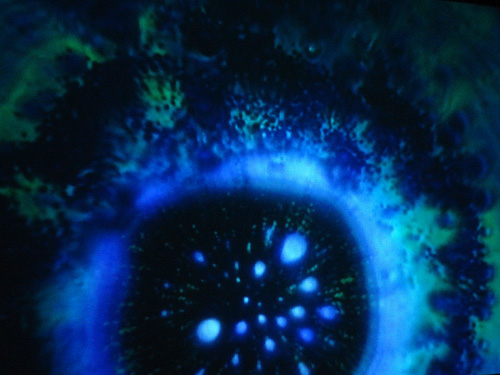

The Joshua Light Show – archive pic

Oneohtrix Point Never’s collaborative show with legendary analogue visual team The Joshua Light Show, on Friday night in Transmediale HQ, proves to be the only time I’ve ever seen his music done justice in the live setting. While Dan Lopatin is twisting new tracks and his Replica album into crackling evocations of net-age digital overload, Joshua White’s collective improvise visual responses in real time. Using dyes dropped in water to send tendrils twisting down the huge screen behind Lopatin, or to bathe it in sensually shifting clouds of saturated red, yellow, and blue, it’s fascinating to see how similar the results are to a lot of current internet art, which often triggers the same New-Agey, floating in the ether sensations.

It’s a reminder that seventies aesthetics have been hugely influential on the current generation of electronic musicians, but it’s unusual to see the two collide as viscerally as they do here. As time is flattened into a single one-dimensional plane by transverse browsable archives like YouTube, this very direct interweaving of old and new – of cause and effect – feels vitally important. Like the rest of CTM’s best moments, when we wander out of the auditorium it could quite easily be anywhere from five minutes to five hours later.