The mercurial nature of Tom Waits and the debates that swirl violently around him – pausing only momentarily in his shape shifting – seem to be universal constants. The various guises and personas he has taken on throughout his career are so utterly perfect and the transitions between them so seamlessly blended, that it is tempting to view him as an embodiment of people’s aspirations – he is the person, or people, that we wished we had enough grit, snarl and fierce talent to be. Most people never get to actually be as cool as they wish they were. Tom Waits has been kind enough to pick up the slack for the rest of us. Cheers for that one, Tom.

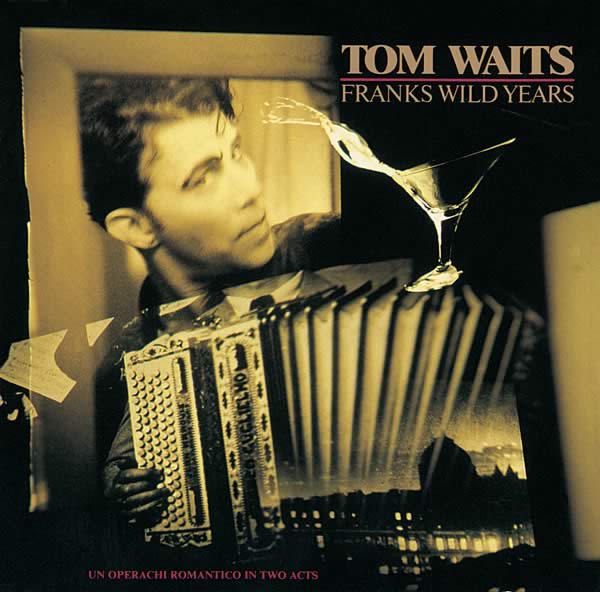

Storms often rage as to which Waits album is the best, with the skies looking to be perpetually inclement. However, it is hard to argue with the fact that the trinity of albums released between 1983 and 1987 are him at his most prolific, fully realised and adept in creating music that unseats and causes discomfort to the stagnant and maudlin. Rain Dogs, Swordfishtrombones and Frank’s Wild Years are an intimidating triad to be reckoned with.

The final offering of the cycle, Frank’s Wild Years, is in some respects the one that stands out as the most individual. A Waits album described as individual and singular when compared to nothing but the rest of the oeuvre? I can already feel the fiery indignation and disbelief; the itching fingers as they approach the keyboard to spew forth a tirade of disdain for this correspondent’s humble opinion… but stick with me on this one.

Although I will never tire of espousing the greatness of Waits in whatever skin he chooses to inhabit, be it as a barfly raconteur, backwoods bluesman, dust bowl poet or absconding guest of an asylum, his electrical, prickly, scathing and firebrand form of the mid-80s is one that may rank as the most fearsome to behold.

While Rain Dogs and Swordfishtrombones are exquisite examples of a vivacity so ferocious that one feels that the albums that contain them can barely keep them from bursting forth and laying siege to all in their wake, Franks Wild Years is a more focused outing. Charting the journey of a small town boy to the metropolis with dreams of riches that are soon destroyed and corrupted along with his person, the album showed Waits trading weapons. Laid aside was the blunderbuss loaded with coffin nails, torn pages of Burroughs, scurvy, hookers’ names and confetti. Instead, his fingers grasped a more precise weapon. His vision was more focused. His targets, more specific. The first two of the trilogy will always be hailed, quite rightly, as sprawling, masterpieces of an eccentric artistry that has few rivals, but it seems as if the third will never be held in the same regard by many. Unfettered mad genius will always seduce and intrigue, but there is much to be said for a narrowing of the scope. Some may be tempted see this as being done at the sacrifice or tempering of energy, but if anything it’s an intensification; a shifting of form; an inhabiting of a new skin.

It has only been in my later life of listening to Tom Waits that I have realised this, which has done nothing but increase my enjoyment and appreciation of this album tenfold. By bringing in the boundaries a little bit, Waits explored in depth ideas, characters and journeys that he only teased people with on Dogs and Swordfish. [Lynn: I’ve had an idea for a new pub called the Dog And Swordfish or perhaps The Rain And Trombone.] If anything, these self-imposed parameters freed up Waits to showcase his flexibility and range; gone was the safety net of escaping to another lyrical or musical shore – this is him pinning himself down and loving every minute of it. He is at his most confident and self-assured. Each song is a platform for a new vocal muscle to be flexed, resulting in a cavalcade of characters under one lyrical roof.

One needs only to pick at random the songs on offer to see this. ‘Yesterday Is Here’ conjures up dust, the night sky, determination and the slow chug of the train. The religious swagger of the mad evangelistic anthem ‘Way Down In The Hole’ places the listener as the out of focus preacher on the streets of a nameless city of iniquity. I have already espoused elsewhere on this site my love of the skulk and sway of ‘Telephone Call From Istanbul’, and don’t even get me started on ‘Temptation’ – arguably one of Waits’ best songs on any album, bristling with angry lust and unbearable beauty, drawing back the curtain to let us glimpse of the doom that comes later.

Waits has often pronounced his love for vaudeville, as well as his wish that he could have been there for it. The attraction of a melange of styles, a mad funhouse of talent, all treading the same bit of stage, is a historical concept that you don’t have to strain too hard to understand his passion for. In a period of his career that is sometimes described as ‘Brechtian’, Frank’s Wild Years comes out as being the most theatrical and cinematic of his albums. This is Waits’ love letter to vaudeville. It is a manic harmony of all the voices and characters in his head, a stylistic gumbo that evokes a time that is not our own now and wasn’t even then, 25-years ago. Yet the emotional grievances and desires that it speaks of are continuous and universal.

As a humble scribe, trying my utmost to put down in words the passion, respect and admiration for an album and an artist that have brought me happiness, it is with great reluctance that I have to dabble in clichés. Themes of journeying and discovery are ones that can’t be escaped. This album charts the wanderlust, desire and frustration of a thankfully under-portrayed character, allowing a greater sense of empathy and identification for everyone that chooses to step on board.

Waits’ undeniable talent for gathering all the threads that everyone has inside them, knotted and frayed, and laying them out bare and making brutal sense of the chaos is what gives him, and this album its emotional resonance. This album is features the singer at his most vociferous, entering a tunnel that can barely contain him and blasting out the other side cathartically and with a vigour that hasn’t waned over the years. For those on the outside, he has disappeared from view and all that can be heard or seen is the trailing smoke and fading of sound. But for those of us on the train, we sit back and are treated to a piece of musical theatre that makes the world seem bright, lurid and garish when we emerge. All that we are left with is a memory and a moment of bittersweet introspection. As well as the ticket to take the ride again.