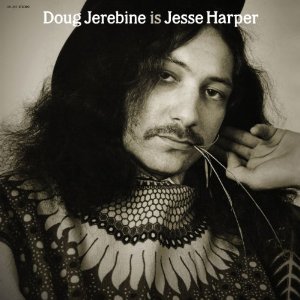

One of the problems with the phenomenon of the rediscovered ‘lost classic’ is that it sometimes mythologises albums that simply aren’t very good. For all those lost and dusty old relics from the 60s that genuinely do deserve affection through a loving reissue, there are many that in their initial obscurity, and the fact they were ignored for 40 years, make claims at being more interesting than the music suggests. That is not the case with Doug Jerebine; his sole album, recorded in 1969, is a fascinatingly original thing, while the man himself has a back-story to conjure with by any standards.

But that should come as no surprise. Is Jesse Harper is out on Drag City, the most discerning label around when it comes to reissues – in the last year we’ve had such magnificent music plucked from the past as Carol Kleyn’s Love Has Made Me Stronger and The George Edwards Group’s Archives. It was also they who reintroduced the world to Gary Higgins’ sublime Red Hash, and in its equal dose of East and West, jamming and songwriting and understatement and virtuosity, one could say Jerebine’s album approaches being an ‘electric Red Hash‘. It is ultimately not nearly of that quality, but as far as psychedelic guitar albums go, this wears its zeitgeist proudly, as well as being a unique sonic curio.

And perhaps that weirdness – mainly conveyed through some primitive effects pedals, some strange and confused layers of distorted guitar and some frankly adolescent lyrics – comes from this man’s life journey. He grew up amid the pastoral climes of New Zealand’s North Island, where he weaned himself on the predictable dose of mainstream English and American rock – he was also devoted to the sitar. After a period in bands at home he inevitably left for London, via a Hare Krishna pilgrimage to India. He managed to record his one album while in the UK, but otherwise fell into a number of unfulfilling jobs amid unsuccessful attempts at music (he auditioned for Jethro Tull and had a miserable experience supporting Jeff Beck).

Then he gave it all up and headed back to India to attend to his true calling: Krishna consciousness, where he has more or less remained ever since.

It’s therefore not surprising that Is Jesse Harper sprawls in all sorts of directions – even if there are some predictable and familiar touchstones. Hendrix is the almighty figure who stands largest over these 10 songs, the differences between the two being a distinct lack of urgency in Jerebine thanks to him not having a rhythm section to complement him (he played all the instruments himself except drums) and the shoddy quality of the recording. On the other hand, Hendrix and Jerebine have strangely similar voices – both a little leaden and monotonous, though not unpleasant.

First track ‘Midnight Sun’, with its dramatic riff and funk-driven rhythm, is the most imitative of Hendrix he gets, but otherwise he shows a kinship with many other major players of the time. ‘Hole In My Hand’ shows the brusque blues of Clapton in Cream while various subtle Beck-isms and Green-isms appear throughout. The attempted interweaving of lines and melodies invokes Richards, while there are certainly enough nods to the drone of Eastern-influenced folk music to suggest he had heard a song or two by Bert Jansch or Richard Thompson.

But after a few listens you realise that a few key factors are standing out above others. Chief among these is the record’s mellowness and restraint. Against the noise of ‘Ain’t So Hard To Do’ and ‘Idea’, the absorbing ‘Circles’ takes centre-stage, while ‘Ashes and Matches’ is similarly downbeat. We may never know if Jerebine ever heard Paul Kossoff, the gifted guitarist with Free who so beautifully defined that band’s drowsy and melancholic take on Brit-blues, but there are several moments from the New Zealander here to warrant favourable comparison.

That wooziness determines that there is certainly no sense of explosive 60s energy or counterculture angst here – given what followed for Jerebine, his chief motive appears to have been to convey some beatific sense of warmth. When the pace is slowed, he undoubtedly succeeds.

But Jerebine seems likely to be remembered as a guitarist first and foremost. For any great pop guitarist, it is not the dexterity of their fingers on the fretboard that defines them so, nor is it how well they come off by technical standards. It is how they explore the relationship between instrument and song, and on this cluttered and imperfect album Jerebine proves himself an honest and heartfelt proponent of the art.