Intro

There can’t be another decade that has furnished us with such an abundance of great music. After the commercial success of The Beatles there followed a massive surge in R&D. Artists were frequently able to release ten LPs in as many years, with many famous names only hitting their stride a few discs in. A multitude more were kept on roster in the hope; their creativity subsidised by bigger acts. Recording technology advanced at breakneck speed in the last years of the sixties so that the expertise, hardware and facilities had reached a plateau of excellence by 1970. When one takes into consideration the budgets and resources available it’s arguable that recording hasn’t been bettered. Even today at the high end of recording the era forms a notional benchmark of lavishness. The record industry has coasted on the fat of the decade for thirty years. Indeed the CD format, which in 1985 brought the end of ten years flat lining of Music Industry profit, was to a great degree built on baby boomers buying reissued material from the seventies and late sixties.

The seventies were a signature decade for Funk, for Disco, for Reggae, for Brazilian music, for African music, Japanese music, for the Electronic Avant garde and for British Folk. However, more than any music, one dominated the media landscape to the extent that Greil Marcus noted that it became “an ordinary social fact, like a commute or a highway construction project. It became

a habitat, a structure, [even] an invisible oppression”. We’re talking about Rock.

Rock’s capacity for growth was enabled by the way in which its host form was heterogeneous. Rock, as concocted in the Sun Studios by Sam Phillips, was the bastard offspring of Blues and Country. An unstable hybrid at its very core, further hybridisation only strengthened it and the seventies saw the boundaries of its form stretched to their very limits. Only at the tail end of the decade did artists like John McLaughlin and Mark Stewart find themselves spilling out, unable to find their style contained within it.

In spite of magnetic tape’s growth through the 8-track, Reel-to-Reel and into the Compact Cassette, Vinyl was indubitably the format of the decade. Reaching unparalleled sophistication in terms of production, Vinyl even embraced outré technology like Quadrophonic, “direct-to-disc” and dbx noise-reduction

encoding. If vinyl was the de facto cultural standard then the long-playing album was its corollary. While the sixties might be seen principally as belonging to the single, after The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) and

through the subsequent decade, perhaps even until New Order’s ‘Blue Monday’ (1983), the LP became the vehicle for self-styled “artistic visionaries”. This hundred Seventies Lost Rock discs is solely comprised of albums.

One of the decade’s key events, the oil embargo of the OPEC Arab nations in defiance of states with a perceived bias in favor of Israel, cut to the heart of insatiable demand for the long-player. A number of top record companies announced that, as vinyl was dependent on oil for its manufacture, there would be no new releases in January 1974. Some observers even ascribe this pivotal date as being the moment at which discs became “noticeably thinner”.

A “Lost” record is not by its essential nature an obscure record. How can something be “lost” if it was never “found”? The cult of obscure records troubles me more when it overshadows the merely less well known. Accordingly many of these discs, were celebrated in their day and were often bought in large quantities. However, owing to the vagaries of fashion they have passed out of the

realms of collective knowledge or else have become hidden in plain view.

Examining the consensus of “greatest records of the seventies” reveals a critical drive that tends to focus on music perceived to have had lasting influence. The result is that the “classics” associated with the decade are remarkable for their timeless qualities. Over time the picture of the music of the seventies has become unmistakably redrawn. This process started swiftly with Post-Punk at the decade’s tail end. Seemingly only The Stooges, Captain Beefheart, Can and Neu! survived the pogrom. In excavating these “Lost” records I will aim to redress this

shiny consensus and by extension try to re-imagine the place in history where we now find ourselves.

Please note that all of these records are interesting but not all of them are excellent! Tread carefully.

- After a record denotes recommended.

** After a record denotes highly recommended.

Rock Fusion

The buzzword for race relations in the seventies was “diversity”. This was the point at which the multi-cultural project first floundered. The example of Huey Newton’s Black Panthers inspired many other ethnic minorities to rail against the patchwork ethos of American society: Hispanics, Koreans, Italians, Poles and

even the Irish followed suit as “unmeltable” ethnics. In the UK, hot on the heels of Enoch Powell’s inflammatory “Rivers of blood speech” there was a similar splintering of racial consensus which was exacerbated by the economic malaise afflicting many Western countries. Immigrants who had been required in the previous two decades to meet a jobs deficit (in the UK many were commonwealth

subjects) often found themselves unemployed on society’s scrap-heap.

The Rock against Racism movement, initially launched in response to comments in support of Enoch Powell made by Eric Clapton, received massive support. Like Clapton, Phil Collins’ card was eternally marked by racist remarks reported in the “inkies” in the mid seventies. These days it’s almost as if people have forgotten the, quite correct, reason for the duo’s original vilification. Heterogeneous Rock was firmly in the “integration” rather than diversity camp. So while other subcultures turned in on themselves, the shift in Sly Stone’s output from Stand to

There’s a Riot Going On often being seen as an archetypal move, Rock struggled for inclusivity.

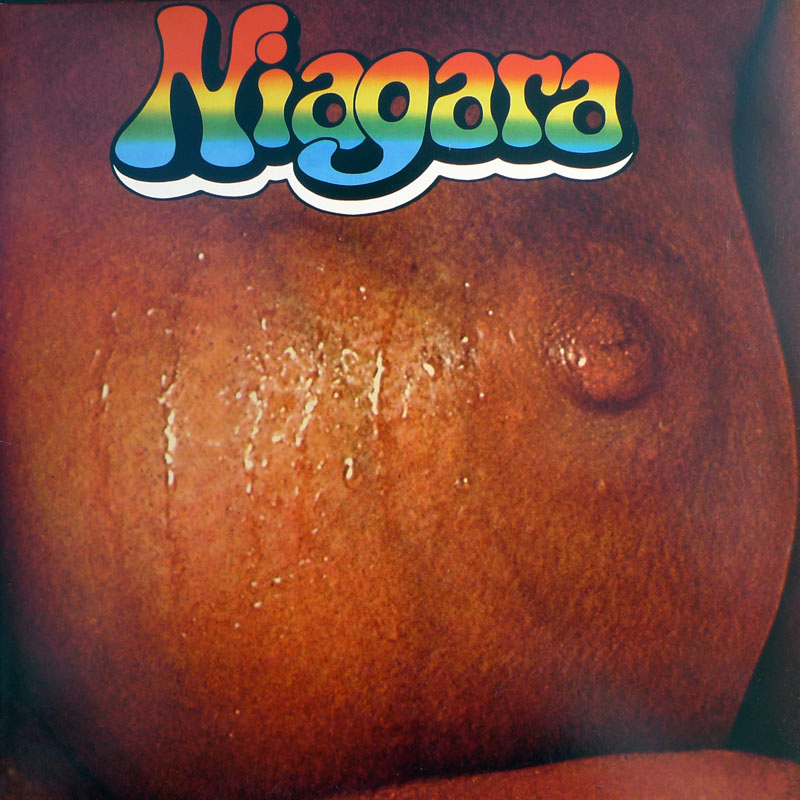

Niagra – Niagra (UA 1970)*

While this classic Niagara album is often lumped in with Brazilian fusion and the like, there’s no fooling me. Niagara were a bunch of German dudes: Listed in the credits besides head honcho Klaus Weiss are Munich Machine mainstay and Billy Idol producer Keith Forsey, Doldinger/Passport stalwart Udo Lindenberg and even Popol Vuh cohort Danny Fichelscher. Yeah baby, this is a monstrous rock jam. Like a drum solo that just won’t stop, Niagara comprises only two tracks of polyrhythmic faux-tribal splendor. The lascivious cover, you gotta hand it to them

it’s a great concept for a gatefold, proved that for all their aspiring political correctness they were never going to make peace with the feminists.

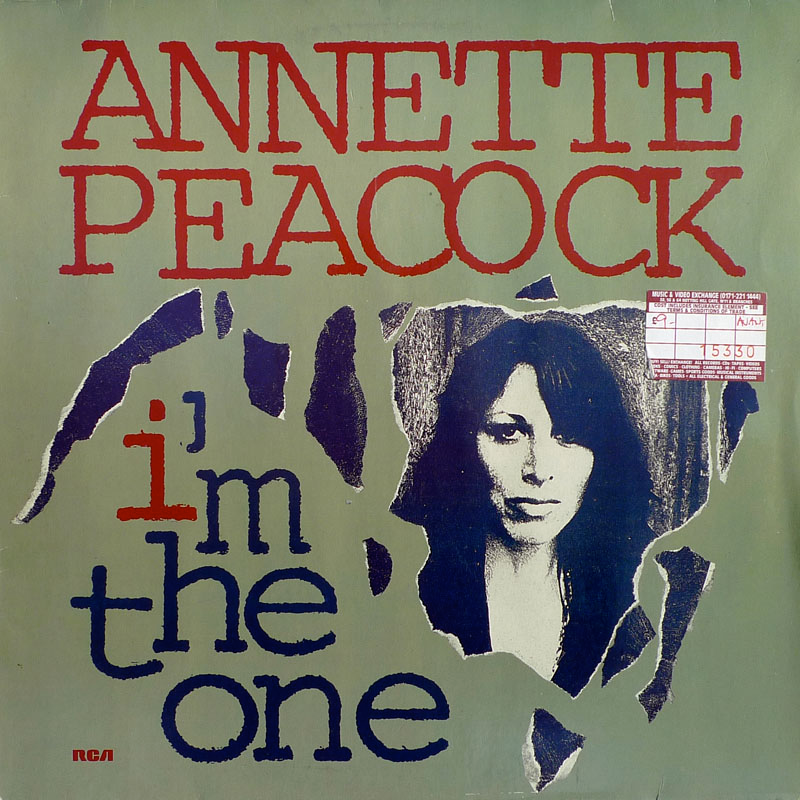

Annette Peacock – I’m The One (RCA 1971)

I wish to god I had an original copy of this with it’s utterly glorious silver, green, blue and red cover. Annette Peacock is almost too good to be true. In the sixties she toured with Albert Ayler AND was a close associate of Tim Leary’s. From the

mid-sixties she devised a way to combine her voice and augment it with the Moog, the instrument that occasionally seems like the only common fascination of the cutting-edge Black and White scenes in this period. She cut I’m The One with Paul Bley, who like her husband Gary Peacock, was a conspicuously white man in Jazz abetted by the open-minded attitude of figures Miles Davis to nurture talent in whatever form. I’m The One is famous for ‘Pony’ which people will keep on rediscovering forever, but the avant-torch song cuts on the disc are also fine.

Mahavishnu Orchestra – Birds of Fire (Columbia 1972)

Another manifestation of Miles’ foray into rock; John “Mahavishnu” McLaughlin met Billy Cobham on the sessions for Bitches Brew (1970). Seemingly carrying the torch lit by Jimi Hendrix forward, the first two Mahavishnu Orchestra LPs,

The Inner Mounting Flame (1971) and Birds of Fire still sound shocking to this day. The brazenly amplified, impossibly ornate instrumentation is yet more inone’s

face than even the most extreme Prog LP, but swings furiously with wild tonality. Even though they were commercially successful, holding position in the new terrain they had created proved impossible, and the band melted down acrimoniously.

Fusion subsequently became either funkified, as on Herbie Hancock’s Sly Stone influenced Head Hunters (1973), or quickly unhitched from Rock and identifiable as a genre of its own. With Weather Report, Chick Corea, the jazz pop of Chuck

Mangione, George Benson and the Crusaders, Fusion became vastly, almost unimaginably successful but also neutered. In this sense, a record like the awesome Birds of Fire is a “lost” album in the truest sense in that it represents an unexplored possibility.

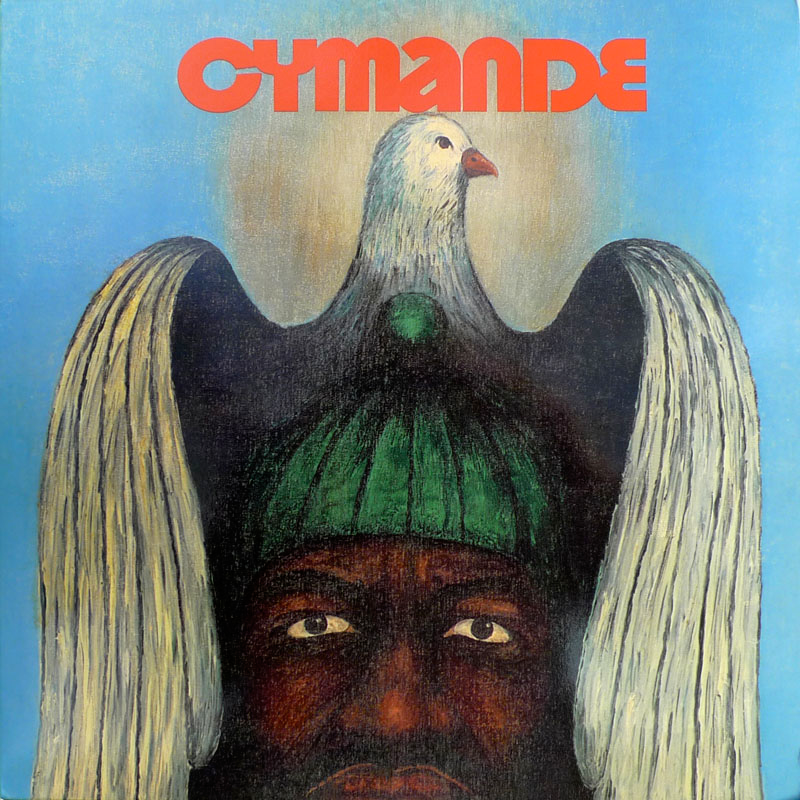

Cymande – Cymande (Janus 1972)*

This excellent album is famous for its cuts ‘The Message’ and ‘Bra’. But wait, cry the sceptical, Cymande aren’t a rock band! I’m not sure whether that given this relatively obscure record by a crack [sic] troupe of Black UK musicians came out in 1972 that mine could qualify as a controversial opinion, but I think they

probably were. I don’t believe their very original fusion of Calypso, Afro-beat, Jazz, Soul would never have happened with the crucial agent of Rock. In the same way that The Selecter would be unequivocally described as a Rock group, so I think, should Cymande.

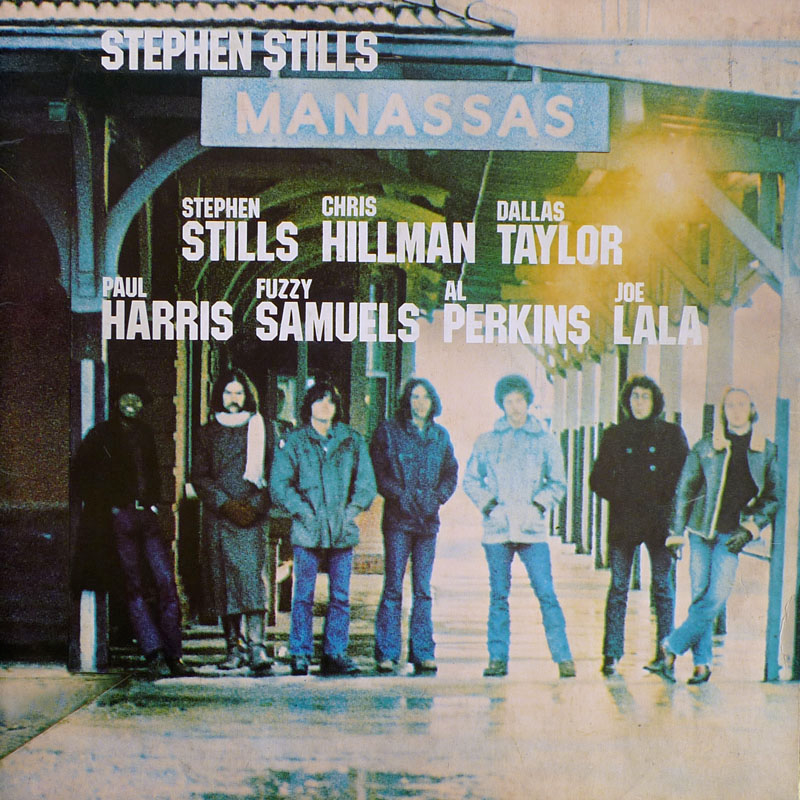

Stephen Stills – Manassas (Atlantic 1972)*

CSN’s break-up gave us at least three excellent solo album’s (famously) David Crosby’s If Only I Could Remember My Name (1971), Graham Nash’s Songs for Beginners (1971) and this lovely double album from Stephen Stills. The surprise with this set however is its heavy emphasis on fusion. The Blues, Latin, Bluegrass, Country and Folk vie for centre-stage, with Joe Lala’s percussion a particular highlight. Stills was valiantly pulling together America’s unfurling strands, perhaps trying to revive the spirit of Woodstock, notable for performances by not just Sly and the Family Stone but also Santana. Despite all this my favourite track is the relatively straight hippy reverie ‘Johnny’s Garden’.

Van Dyke Parks – Discover America (Warners 1972)

In the shadow of his panoramic work for Brian Wilson and Song Cycle (1968), Discover America is one of the weirdest, far-sighted documents of multiculturalism in America that you’ll ever come across. It wasn’t until Sun City Girls and Panda Bear’s Person Pitch (2007) that the rest of the nation caught up with the idea that beyond being a polyglot nation America actually belonged in the wider world. There can’t be many albums that start with someone else’s track, but Discover America kicks off with a large section of Mighty Sparrow’s ‘Jack Parlance’. Beyond the odd thirties Jazz style cuts (‘Bing Crosby’), Reggae versions (‘John Jones’ though via Byron Lee and the Dragonaires off-island waxings) and a take on Allen Touissant’s New Orleans standards ‘Occapella’ and ‘Riverboat’, this travelogue is essentially Van Dyke’s homage to Sparrow and

Lord Kitchener’s Trinidadian Calypso. The impatient should head straight for ‘Your Own Comes First’.

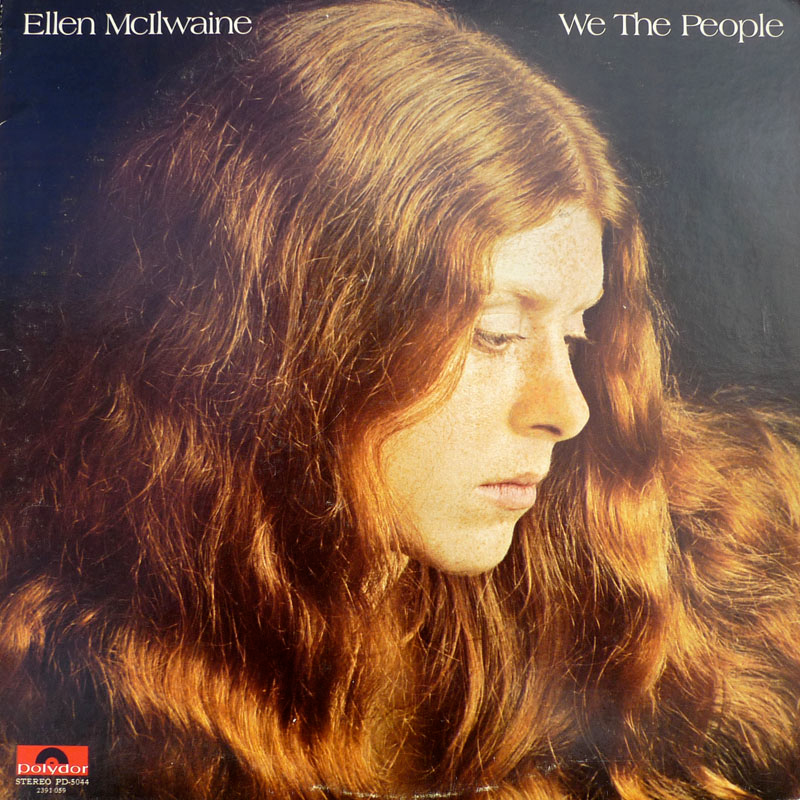

Ellen McIlwaine – We The People (Polydor 1973)

Nashville-born Ellen McIlwaine was adopted by missionaries and raised in Japan, Ellen was “diversity” embodied. Gigging in Grenwich Village she befriended the young Jimi Hendrix and opened for blues greats like Muddy Waters. We The People is a veritable patchwork of Gospel, Blues, Jazz, Funk and Folk hard-driven by almost Zeppelin-esque slide guitar work. Her ‘Jimmy Jean’, with its delicious scat yodel, was a Patrick Forge and Gilles Peterson Acid Jazz staple and was even reissued under the auspices of that scene. We The People is this funky mama’s strongest disc and well worth a listen.

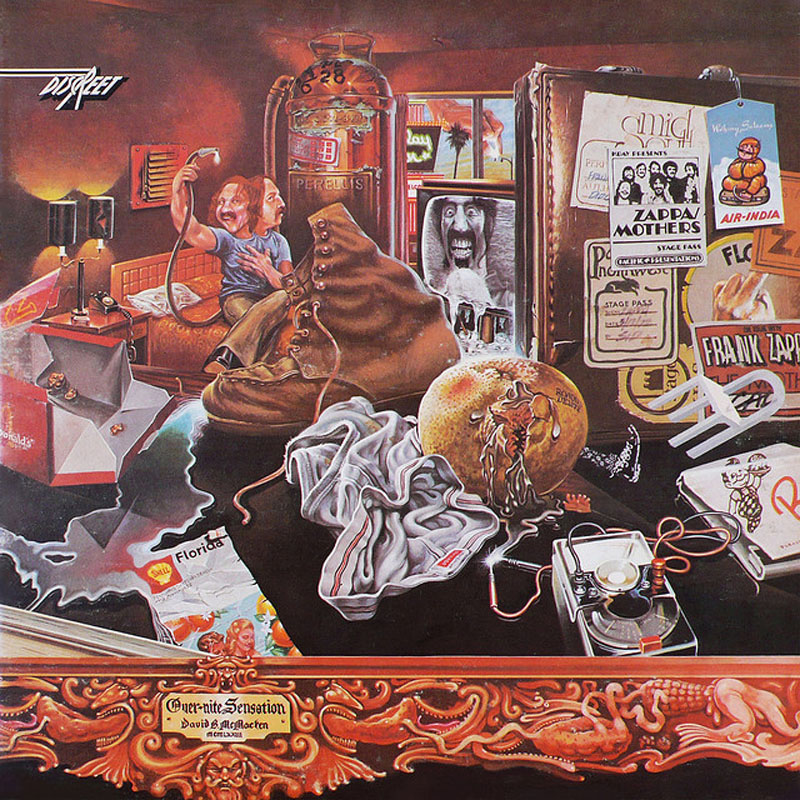

Frank Zappa Over-Nite Sensation (Ryko 1973)

Poor old Frank. It seemed as much as he strived for the artistic high ground the more critics made a point of preferring Captain Beefheart. Anyone my age in the UK grew up with a rock press that dictated Beefheart good, Zappa bad. The comparison between Zappa and Beefheart is unfair, they’re radically different creatures, but Frank is cool too. Beyond his Mothers of Inventions “classics” (Uncle Meat (1969) being perhaps Prog’s original stone tablet) some of his seventies discs are excellent. Both One Size Fits All (1975) and particularly Overnite

Sensation are by turns hilarious, wildly intelligent, almost excessively well played, and of course finger-snappingly fusion-tastic. More than any other Rock giant of the seventies Zappa had an awareness of the full spectrum of music. He ropes in George Duke and Jean Luc Ponty on Over-nite Sensation and damn near outplays ‘em both. Sick.

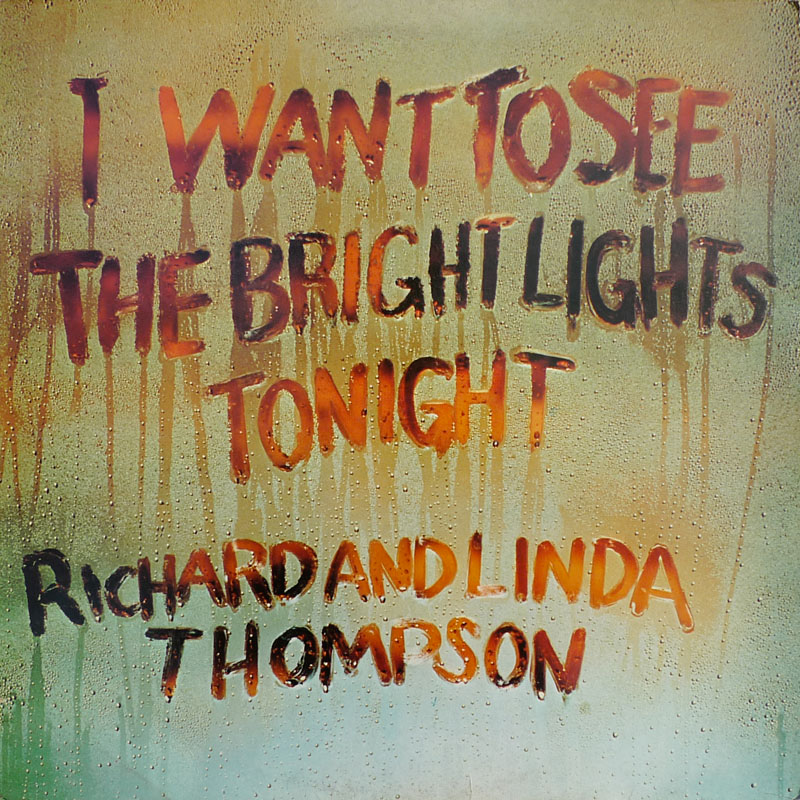

Richard and Linda Thompson – I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight (Island 1974)**

Not all Rock music strands of the seventies embraced integration above diversity. In the same way that as the decade progressed one was less and less likely to see white faces in predominantly black Funk groups (witness the shift from Booker T and the MGs’ equal racial split to Kool and the Gang’s solid brotherhood), you’d be hard pressed to find a black or brown face among the ranks of Britain’s Folk Rockers. Folk Rock was, as preoccupied with racial agenda as the civil rights movement, even if its aims were more poetic than political. However, in the same way that R&B was the unwitting passenger of Punk’s Trojan horse, so it was with Folk Rock.

The further Folk Rock travelled from the Blues towards a notion of purity, the sillier it became; most notably the Morris On albums, the later Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span’s output. Conversely the most interesting Folk Rock did in fact work to an agenda of diversity – John Martyn’s One World (1977) or the Incredible String Band’s The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter (1968) with its global folk collision of Celtic, North African and Greek music. Richard and Linda Thompson ended up the end of the decade as Sufi devotees and could hardly be described as your typical Nationalists.

This might be the most contentious inclusion in this “lost” hundred. When I first started following music closely twenty-five years ago, this record was everywhere. Strangely though it seems to have receded into the collective unconscious. It doesn’t even receive thick coverage in Rob Young’s landmark study of the UK

Folk music continuum Electric Eden. People have even ventured to supplant it with other of Richard and Linda’s records like Pour Down Like Silver (1975) or Shoot Out The Lights (1982). You must hear this wonderful record, to my way of thinking the greatest British Folk Rock album of them all.

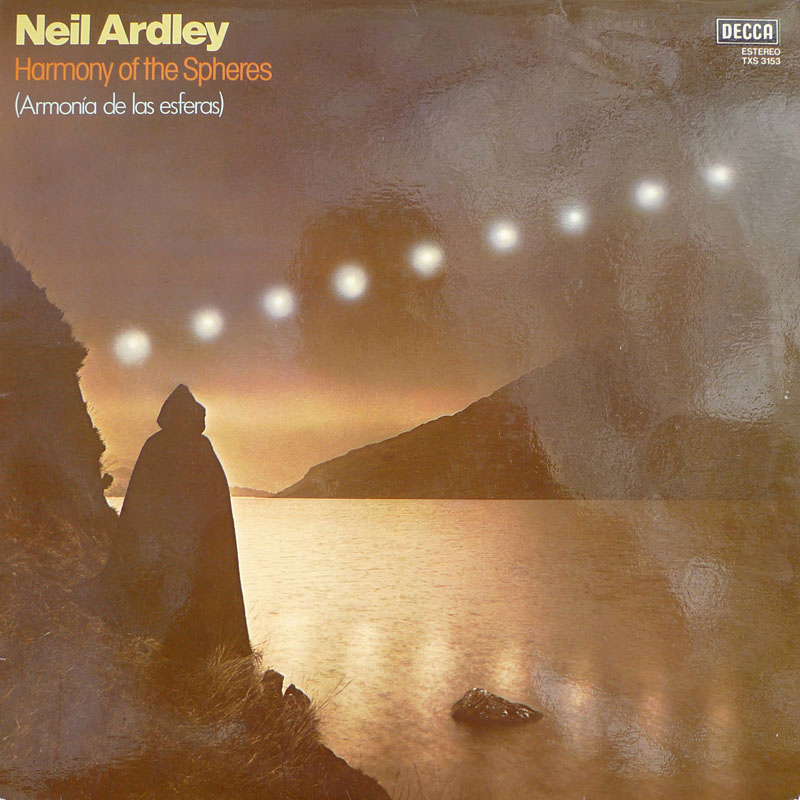

Neil Ardley – Harmony of the Spheres (Decca 1978)**

In theory this was a British Jazz album. That, scorned by purists, it was more of a Jazz Funk album with a heavy presence of synthesisers, and that Folk rocker John Martyn played all over it, leads me to conjecture that actually it’s a rock record not a million miles from Brand X’s territory. This lithe Space Rock, the twin sister of John Martyn’s Moebius-loop excursions, would be manna to fans of the rhythmic densities of Krautrock and Post-Punk. What a fantastic record!

To buy Matt’s ebook for the princely sum of £1.98 just click here

There will be a new Woebot album by the end of the year