At the start of Lawrence Of Belgravia, the eponymous subject of this feature length documentary looks into the camera and asks: "Are you ready Paul?" It’s a question that is never truly answered, as we get the impression director Paul Kelly might indeed not have been ready to embark on a film which ended up taking eight years to make. But Kelly chooses not to focus on the many ups and downs during that time, allowing a minimal number of images of methadone, notices of eviction, CBT charts, arrest warrants, and a visit to the Royal Courts of Justice, to stand as evidence of a life unravelling. Instead he mounts a deeply personal investigation into what makes Lawrence tick, a film portrait of someone who cares little for everyday things, but instead obsesses about his art as a musician to exclusion of practically everything else.

Lawrence Of Belgravia is a film about the struggles of being an artist, and feels as if it could only be made by someone like Kelly, with his love of music, film and photography. Kelly was guitarist in various bands including East Village, Birdie and Saint Etienne, as well as making the films Finisterre, What Have you Done Today Mervyn Day? and This Is Tomorrow with them.

At the beginning of the film, Lawrence is facing eviction and Kelly gently details his move into a new flat, juxtaposing this with Lawrence’s eternal quest for pop star status. As he nervously attempts to paint the walls, Lawrence muses, "I wonder if Lou Reed’s ever painted? I can’t imagine him getting the old roller out." The contrast between his vivid dreams of popstardom and the realities of his daily existence form the backbone of the film, which is at once a funny, sad, insightful and refreshingly honest meditation on the mundanities and the mythology of rock and pop.

Lawrence ‘s music career started in 1979 with the release of the single ‘Index’, and over the next decade his band Felt produced 10 albums to critical acclaim and a cult level of success, while also releasing 10 singles, which almost saw him scoring a crossover hit with ‘Primitive Painters’, that featured Lawrence duetting with Cocteau Twin Liz Fraser. Disbanding Felt, Lawrence formed Denim, a power pop juggernaut of a band seemingly created to be the polar opposite of Felt’s polite guitar tunes, and alienate his former audience. The general public again seemed resistant to the immensely catchy three albums that Denim put out. Once again he killed off his creation and started again in 1999 with his latest and still current project Go Kart Mozart, and the film details the everyday struggles he goes through to make sure his new album On The Hot Dog Streets gets finished. "Luckily I’m insane, it’s the only way I can make music," Lawrence deadpans at one point. At times when watching this film, you will find yourself agreeing with him.

I was at the premiere screening at the British Film Institute where you did a Q&A after the film and you seemed quite moved by it…

Lawrence: You know what? I was. I was quite choked. There are these three little steps going up to the BFI stage and I thought ‘I’m not gonna make it up them.’ I was really… it hit me… when things like that happen, that you don’t plan for, that you don’t understand, it’s really odd. I’d never seen myself on screen, I’d not been in a band that made videos, and I’d never seen the film before. It’s Paul Kelly’s film and I didn’t want to get involved because I’d start to try and get my point across. I didn’t want to invade his space. It’s his film, it’s nothing to do with me, it’s his portrait of me. So I’d purposely not watched it. I mean, I’d seen a few clips round at his studio, he’d shown me on his computer, so I’d seen bits of it, but that was the first time I’d seen it all the way through, it moved me, it was an emotional night. And the reaction from the audience was incredible.

Did you slip into any other screenings?

L: I’d have loved to watch it all four times [at the London Film Festival] but I like to keep the mystery, so it’s best not to… The big night was Saturday. There was no going back after that, I had go into the cocoon after that and play the character.

Paul did say you had a few arguments along the way

L: We had one major row. We had one major fall out where the film nearly didn’t happen which is pretty good going in all the years we were filming.

I did ask him if there were times when you thought it was never going to get finished. Were there times for you?

L: Oh yeah. Millions. I think there were tons of times, there were periods where we didn’t see each other for six months, because I was in hostels. We sneaked a camera in one of the hostels which you see in the film, but the other hostels were impossible. I was kind of homeless. It was hard to put that on the screen, that’s what I mean that we’d have needed secret cameras and microphones. There were periods where we didn’t see each other for six months as I was in a hostel and things were so bad… and other times he had to do work as he has a family and has to earn a living. It wasn’t like we were shooting continually. Each time that happened I would think, ‘that’s it now we’re not gonna pick it up, the break’s been too long, he’s sick of it now, he’s sick of my predicament, he doesn’t want to do it anymore, because it’s too troublesome’.

I’ve seen Paul’s work with Saint Etienne before but this one seems more personal, as if he was more directly involved with the subject matter of the film.

L: Paul was the one constant in my life as we were making it, all the way through that period… and a lot of the time I talked to him as if he was part of the film when he wasn’t, I’d kind of forget, and talk to him as part of the film. A great illustration is at the start of the film when I go ‘Are you ready Paul?’ just before I started talking – and I loved the way he kept that in. His films… this is his coming of age film. The films he’s made so far are building up to this. This is his first feature film. The Saint Etienne film is 1 hour 10 minutes, and I said to him, ‘if we’re gonna do this it has to 90 minutes or it won’t get taken seriously as a cinema film, it has to be 90 minutes.’ Otherwise it’s just a documentary and it’s not given that gravitas that a 90 minute film is given.

Although it’s about you and your dreams, it’s also seems to be about Paul and his dreams.

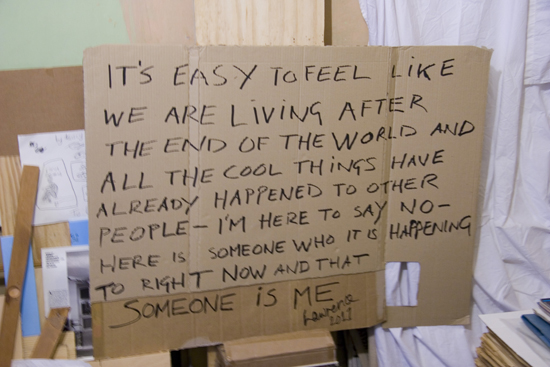

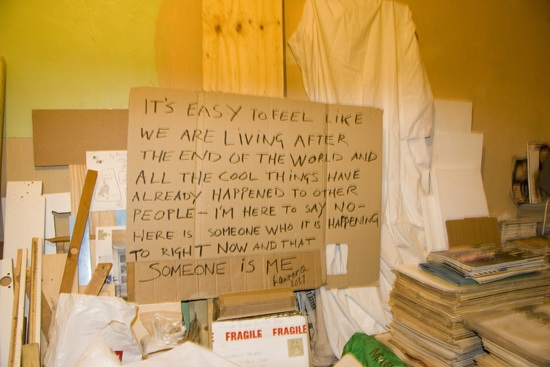

He’s continued to be an artist. A lot of people give up their dreams when they reach a certain age, and especially when they have a family, and both of us haven’t given up our dreams. His dreams have taken him in a different way, where he’s stopped being in a group and he’s gone back to what he started doing, messing with film and photography. We’ll both continue to be artists in a world where most people have to give up by the time they reach their forties. Real life gets in the way usually. I think we’re trying to say that it doesn’t have to, and there are some people who just carry on, battling against all the obstacles, and they’re not going to give up until they’ve got there. And I think he got there with this film. We made it! On an artistic level it’s a real triumph.

Do you like rockumentaries?

L: When Paul said to me, ‘My next film is going to be about you’, I said, ‘OK then’, but I said, ‘I don’t want to make an ordinary film, I don’t want any talking heads, I don’t want you to go to any people who know me and get a critique or anything like that, what I don’t want to see in a documentary is someone who’s been in a band years ago and then you see them and the other band members fat and old with grey hair sitting in a pub reminiscing. I hate that, it’s just such a boring technique. Paul said exactly the same, he didn’t want to make that sort of film in any case. I think it’s great to watch films about musicians, I really like it, but there just aren’t any good ones made. Me and Paul, we like Dig! and the Daniel Johnston one, and we wanted his film to be like the third one. If there was a triptych of the best rock documentaries we thought ours would slot into that with Dig! and The Devil And Daniel Johnston, the best ones of modern time. I don’t know if you’ve seen any better ones?

The two you’ve mentioned there are about artists who are quite idiosyncratic individuals…

L: But if you’re gonna make a documentary you’d do best to make a documentary about someone like him who’s interesting, because a lot of people in bands… a lot of people in bands are very, very boring.

I’ve heard that rumour… so I said to Paul that last shot is amazing. (Lawrence is seen standing on the balcony of his new flat and very very slowly the camera pulls out to reveal the sprawl of London’s skyline behind him and Lawrence a tiny figure in a huge landscape)

L: It’s one of the lucky accidents that happen in film making, you look at it and think ‘how did they do that, they must have spent the whole budget on a crane shot!’ But Paul lives in a block parallel to me, about five minutes walking distance, I’m on floor 12 and he’s on floor 17 and we can look at each other and wave our flags, so Paul said ‘I know the last shot.’ It’s a great idea, I think it works beautifully, especially with the music, it’s such a sad song, he chose all the music as well, none of it is my choice. It’s actually great to hear the music – if I had been able to choose the music it would have been totally different, it’s lovely hearing someone else’s choice of all my music… but yes that last shot is remarkable.

The film looks big budget in some ways… it’s beautiful.

L: I said to him ‘people are going to copy your style, because it’s unique what you do, you don’t do pans, don’t have cameras moving about, you don’t like MTV style, you don’t like the modern way of using the camera, on the hoof on the run’. He likes it with a tripod, and it looks filmic, a filmic quality.

You did have a lonely hearts advert in the film… (Lawrence’s lonely hearts ad lists ‘liking walking the streets’ and being into ‘peeping’ and ‘genital mutilation’ amongst his many interests)

L: I know , yeah.. I’m showing him how far I’ve got with the sleeve notes for the album, and it’s like a lonely hearts, I always do sleeve notes. I couldn’t believe what I’d actually written, I thought ‘What did I write that for?’ But it rhymes you see.

Paul said he was terrified as you were sat beside him at the premiere.

L: There were no bits where I thought ‘You shouldn’t have done that’. He told me afterwards ‘You were just watching it like a punter’, I said ‘Yeah I felt like that’ ‘cos he was watching it down in his seat, wandering what was gonna happen, while I was watching it, enjoying it like an audience member. I don’t know why I could see myself as a character so easily. Right at the beginning when he first asked me I had to think hard, and I thought ‘OK, this fellow’s going to make a film about me, sometimes I’m going to look terrible, sometimes I’m not going to look like I usually do in photographs where I have total 100% control’, and I had to relinquish all control and by the time I saw it on the screen, all that had gone away, all that worry that you might have had, I didn’t think anything like that. I’d made a bargain with myself right from the very beginning, this is the way its going to be, you’re just going to have to accept that you’re not going to look the way you want yourself to look. But it’s a film…

What made you trust Paul and agree in the first place to do it?

L: Well, we met because he was doing some sleeve designs of reissues for me, and he was finishing making the Saint Etienne film and he asked me to do a voiceover on it and I started watching that and I thought ‘Wow, he’s a great film maker, I love this film’ and I didn’t mind doing this voice over, I wanted to be part of this film and he said ‘The next film I’m going to make is about you’. I thought it’s a privilege that he’s asking me, that it’s a privilege that he asked me to be his next subject.

It’s nice timing with the new album (which is due out in 2012).

L: It’s nice that everything is coming out over a six month period, there’s a photobook, there’s two albums, and there’s the film all over six months. For me that’s remarkable really… [pause] You might never see me again for 20 years.

In the film there was a bit where you said you wouldn’t appear on other people’s records.

L: I don’t like all that. I don’t like that ‘all pals together’. Even though I’ve got lots of friends in the music world, as a fan, I don’t like when people get together to make a record. Just because you’re friends doesn’t mean you should make a record together… or because you like someone else’s music you don’t have to get them to guest on your record. I just don’t like that pally pally mens club thing. And as a fan, say I was a 16 year old kid, being a fan of the music scene, I’d feel a little left out. Music is a really serious business, and it’s a solitary pursuit, I think.

What if you got offered loads of money?

You don’t though. All you get is people you’ve come across going ‘let’s make a record together’. I did get offered a money job by people I’d never heard of and I turned it down and that was a big job. They wanted me to write the lyrics for an album. I wasn’t going to sing on it, I was going to write lyrics. And choruses, ‘cos they couldn’t write choruses.

Do you ever get asked to write advertising jingles after ‘Novelty Rock’, as that was especially full on insanely catchy tunes?

L: I think that [the track ‘The New Potatoes’] should be on an advert. The publishing company I’m with have only just got someone on board for that. I said ‘Look, I’ve got a song called ‘Supermarket’ which would be perfect for Tescos’. I can just imagine ‘Supermarket’ on a Tescos advert. It just repeats Supermarket in a vocoder voice over and over… ‘New Potatoes’ could be.. so many of them could be on adverts.. that’s the kind of income I need..

Never been approached?

L: Never. Nor soundtracks. I think it’s all… I’m a late starter.

I was saying to Paul that there’s an optimism in the film, you and Paul are in your 40s and it’s alright to still to have dreams and ambitions.

L: I’m one of the last of my generation who has kept going without success and I have a healthy optimism. Musicians… there’s a lot of bitterness. You know that Morrissey song ‘We Hate It When Our Friends Become Successful’? That is so true in the music world. But I’m not like that at all, I wish everyone well, because I think they might help me, If someone I know becomes successful they can help me. It’s when you go away that the trouble starts. You must see it through to the end. Everything you do, see it right through to the end, because it will always come good in the end. I believe that it will come good… one day. I don’t know how long it will take. Sometimes I say I will be the first rock & roll pensioner, but… maybe I will be.

And you always have a great body of work that no-one can take away.

L: I just think optimism is healthy, it gets you through.

It’s allowed when you’re twenty, but when you’re forty you’re seen as deluded.

L: It’s a new concept, because in the past when you reached a certain age you were meant to pack your bags and get lost. ‘Get a proper job’, like our mothers would say. It’s never been done you see. Our world of rock writing, pop song writing, it’s really new, so there aren’t any old men yet.

But it’s also like a dying culture in a way. When you talk in the film about how important record sleeves are to pop culture, it sounds like you’re talking about the past, and the internet seems to be smothering that music culture…

L: It’s spoiling it for me. If I was starting out now, I don’t know if I’d do a band now. It’s sad that the world that I loved and was part of is changing beyond… there’s no going back it seems. But what is changing for the music industry is not so bad for my generation… It’s just reducing itself back to a cottage industry which it was in the first place anyway. It was only with the advent of Beatles that it all went massive big business. People say ‘it’s the end’, but it’s not the end, it’s going back to being a cottage industry again.

Mick Jagger was saying the 60s, 70s and 80s were an abnormality as far as a music industry was concerned.

L: When you’re reading biographies and books, it’s such a shock, especially when they hit Woodstock, everyone in the music world can’t believe it’s happened, it’s big beyond everyone’s wildest dreams…

The brilliant photographer Leee Black Childers was saying how back then no one had a plan.

L: John Lennon said he thought it would only last six months for the Beatles, or maybe a year at the most, and then he’d have to find something else to do. They really didn’t think about it in the long term, it sounds mad now, but that’s what they were like.

You’re very self aware about your mythology.

L: There’s no point in just being in a group, you want to be in a band, make great records, have a biography written about you, have a film made about you, it’s all part of the deal for me. I was thinking about that before we’d even done our first gig. I was thinking ‘what’s the biography going to look like’. I was always thinking. I kept a diary for the first ten years, I purposefully kept a diary so that I’d know everything that I did for the biography. So I’ve always been thinking of things like that. But i didn’t really think there’d be a film. So that’s a bonus for me.

Presumably there will be dvd extras?

L: If it was me I wouldn’t do extras, I don’t like extras. I think when you make a record. I hate this new way where you put out-takes and acoustic versions of songs. When you make a record you do the best songs you have at that moment on the record, I don’t want to hear the crap that they done afterwards. So with the film, I just want to see the film that the director had in his head. The extras are really what was on the cutting room floor. Having said that, our extras are brilliant. So many great bits didn’t make the film. I know, he’s told me he’s going to extras. But it’s the sort of thing that I don’t do.

It’s interesting with your film it’s taken eight years but it looks like about a year.

L: No-one knows it took that long. When [Paul] tells people, I keep saying ‘Don’t tell them how long it took, keep it mysterious’. He always says ‘eight years of my bloody life’, he’s all weary.

But it adds to the mythology in a way. Part of me wonders about the gaps, because it appears quite seamless.

L: I think he did a really good job. He’s made his films without any budget. Sometimes he’s had an extra cameraman but that’s all. It would be remarkable to see what Paul could do with a proper budget. I’m like Paul Kelly’s cheerleader. I think after all this it would be terrible if he didn’t get a big commission out of it. He could make any type of film.

What about your favorite films?

L: Christiane F, I love that film so much. At the end of our film, when I put the white label on the turntable there’s a lobby card from Christiane F on the wall, I’ve got all of them. One of them is on the wall, a picture of her shooting up in a toilet, I love that film, I’m in love with that girl. She was I think 14. And I love the real Christiane F as well. I’ve got pictures of her. I love teenagers. I like Larry Clark, I’ll be like Larry Clark mooching around kids when I’m older, I’ll be one of those suspicious guys. I really do love teenagers, because they’re not bogged down by the mundane aspects of life, and are still full of hope. I love teenage films, Kids by Larry Clark, that kind of life, Streetwise.

I remember the bit in ‘Streetwise’ where a kid dies and his father is allowed out of jail and he puts his can of coke on the kid’s coffin.

L: …And the Tom Waits soundtrack. I love films like that about kids. I also love The Mother And The Whore, that’s my favorite French film ever.

I wish I’d seen that as a teenager…

L: They spend the movie just hanging around cafes, pontificating! It’s amazing isn’t it? It’s a real critique of a middle class lifestyle gone wrong. He’s poncing off two women, it’s fantastic. French films are great, because they were serious about film, that was their life, Godard, Truffaut, all them guys. I’d just combust without film. Film was the way musicians should be about music but they’re not. The French ones and Francis Ford Coppola remortgaging his house and getting into so much financial trouble because of Apocalypse Now. Martin Sheen had a heart attack, Coppola didn’t care, he sent him to hospital and got on with the film. It’s a love of art. Art comes before anything else, I just love that. I don’t see it enough in music, that’s why I tend to love film. You see it in film more than in musicians, they don’t strive as much as filmmakers. Like Herzog and Kinski. Kinski pretends he only does the films for the money. But you can tell he loves film.

But it always took Herzog to bring out the great performances

L: Kinski is probably in the top three actors ever, he’s a phenomenal actor. He used to do stage plays, remarkable massive feats of remembrance on stage… and then he does all these films for the money. He didn’t work with enough great directors. Herzog was the guy who showed the world what he can do.

What about future films? Would you consider being in one?

L: I’d love to act in a film now, a mean moody role where there’s not much dialogue, where I could hang around the side of the set smoking, like Bob Dylan in Pat Garrett, a part like that with not much dialogue. I’d love to do a film, love to work with a great director… the character would have to be a misanthrope or something. Because I could play that part really well.

What about doing film soundtracks?

L: Instrumental music is music without the film really. Instrumental music is begging for visuals.

Do you think Paul captured the real you?

L: Absolutely, he’s really got me, I didn’t look at it and think ‘Who’s that guy?’, I thought ‘That’s me’ or one aspect of my character. If people do think they can come up and talk to me, we’ve done our job really…

Did people come up to you after the film?

L: At the premiere, there were people who for the first time came up to me and were asking, ‘Can I do a photo with you?’ and I said ‘No’, straightaway. ‘Cos I’m not that personable, there’s no way I’m standing there doing photos with fans. I don’t do that thing that all celebrities do now, where they pose with them. I’m not that sort of person. I’ll sign my name but that’s it. I draw the line.

Finally Lawrence, are you an optimist?

L: Oh yes of course, I believe it’s gonna come right in the end, I’m going to make a living from music. Because that’s what I want, I just want to be able to make a living, that’s what it’s all been about. Life’s a comedy, so many things go wrong, you’ve got to laugh at it. And that translated in the film well I think, people laughed along with me, not at me.

Check the Quietus on Friday for an interview with Lawrence Of Belgravia director Paul Kelly. Lawrence Of Belgravia will be screening around the UK in April 2012, for further information visit the Heavenly website. Nicholas Abrahams is currently working on a film about Jayne County. To find out more about his work, please visit his website