“You’re a load of fucking wankers. If they’ve got something to say, why don’t you let them say it instead of just sitting there like a load of tits; like a load of wankers. Could you do any better? You’ve got nothing to say. You’re just idiots y’know. You’re so bloody ignorant it’s unbelievable. Go on! Come on! Anyone think they know what they’re talking about? No? You’re a load of fucking wankers, you really are.” An unnamed Brighton DJ shouting at an unappreciative TG audience, March 26, 1976

These records were never supposed to be repressed. The inventors of industrial music, Throbbing Gristle, raised £150 to form Industrial Records and then another £700 in 1977 to get 785 copies of The Second Annual Report pressed. They’d already self-released two albums which they’d given to friends on cassette but their first official release was going to be a compilation of live ‘documentations’. Most of this money came from Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson, an electronics and tape operative for the group. He had more money than the other members because during the day he worked as one of three partners at the Hipgnosis design agency. This punishing dual schedule of arcane, occult, narcotic musical research at night and design during the day was something he kept up long after TG split in 1981.

The first 500 copies of the album sold – almost entirely by word of mouth, no advertising – paid off their debts, while the final 285 raised enough money to record another album. And while there genuinely are still a few squat ravaged men out there grinding down their tiny nubs of teeth at the betrayal caused by these beautiful reissues, (already pushed toward the brink of psychosis in 2011 by similar treatment of CRASS’s back catalogue no doubt) they have, as always, missed the point. If you isolate this one statement of intent, it shines out as having more significance than most of the platitudinal rubbish spouted by nearly all other bands during their entire morbidly obese careers. Most modern bands are quick to claim that they just make music for themselves. This is to kick dirt over the fact that they either don’t know why they make music or to disguise the fact that the music is simply secondary to the pursuit of money, intoxication and sex. They are of course, fucking liars. Only Throbbing Gristle had the right to the mantra: We just make music for ourselves, and if our audience hate it as well – then that’s a bonus.

Their statement was intended to convey the fact that they were not indulging in a commercial enterprise; they were not making a form of popular music, like punk or disco for example. They were not a punk or disco band – even though people would confuse them for former, they had more in common with the latter but only by a few scant degrees. (It would be perhaps fairer to say they were a post punk band who formed (just) before punk happened and remained one until (just) after post punk ended. Throbbing Gristle got lumped in with punk for fairly understandable reasons but they had little in common with the Sex Pistols or The Clash. [There was never any chance at all of seeing Pan’s People doing an interpretive dance to ‘Very Friendly’, no matter how intoxicating a prospect that is.]

Perhaps only CRASS shared any common ground with them, given that they were both interested in using the apparatus of control to break down control systems, they were both philosophically driven units that had more in common with the (far more radical) late 1960s counterculture than they did with the prevailing ‘nihilist’/’anarchist’ orthodoxy in the late 1970s, and they both rejected dunder-headed masculine aggressiveness for something far more effective and vicious. (Obviously, in other ways they were nothing like each other; while they were both sworn enemies of capitalism and the bourgeois society, CRASS opposed these things as utopian anarchists. TG didn’t so much oppose as expose; and they seemed more resigned to a life trapped in dystopia not fighting for utopia.)

But really, when all is said and done, they truly were sui generis, sharing only certain spiritual and functional strands with one or two other groups of the day such as Joy Division, Cabaret Voltaire, Nurse With Wound and Public Image Limited. Christopherson, along with Genesis P-Orridge, Cosey Fanni Tutti and Chris Carter, invented industrial music and have towered over the genre artistically for the three decades since – despite being dormant for most of that time. They were as important in their own right in the development of the networks and philosophies used in the rise of independently produced and distributed music as CRASS and Black Flag were in theirs.

The CD is probably the better buy over the vinyl, simply because of the extra material and ever so slightly louder mastering but both are worth owning. (The vinyl’s relative quietness after all can be fixed by simply turning the volume knob up on one’s stereo – something that seems to have escaped the notice of many angry people on the internet recently – and the wax comes with really good booklets, containing reviews and photos from the band’s archive.) The second disc of the CD here is made up of seven extra live recordings made mainly in 1977, as well as ‘United’ and ‘Zyklon B Zombie’ (based loosely on VU’s ‘I Heard Her Call My Name’) taken from their first 7” single. There is almost a recognisable song structure to ‘No Two Ways’ (Hat Fair, Winchester), given that it sounds like Hawkwind undergoing painful spaghettification as they come within the pull of a black hole. But ‘United’ is perhaps their first ever ‘pop’ song and I can’t be the only one who finds TG even more unsettling when they’re being pretty.

But the rest of the material here is remarkably ugly – not just in the harshness of the music, the offensiveness of the lyrical content, the disturbing nature of the packaging but even down to how it was recorded. Absolutely nothing was left to chance in the assault on the listener. P-Orridge described it as “one in thee eye for hi-fi freaks” – a gross understatement, given that it is sheer zero point one percenter music. Even the lo-fi recording technique on its own is enough to put most curious listeners off. The entire first album bar ‘Cease To Exist’ was taped on a Sony cassette recorder through a condenser microphone onto a home stereo cassette. The album was mastered on a portable Revox unit hired for the day. The tape they used was second hand and it was only Christopherson noticing that you could still hear an orchestra playing underneath the tracks that saved the album. But this churning sonic distress was essential to TG. The swamp of hiss and electronic crackle that frames early TG recordings is the thing that makes you forget that you are listening to machines. Sounds that should be pure and clinical become organic and occult.

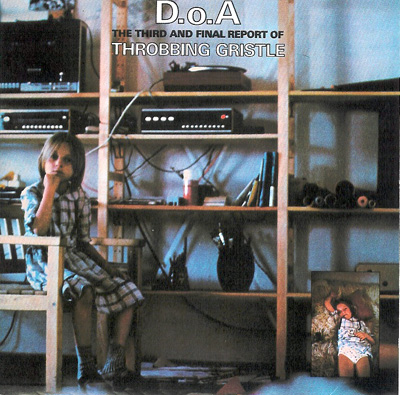

Not that there’s much in the way of lush and pleasant melody here. For example, ‘I.B.M.’ is more musique concrete of data transfer noise overlaid with guitar feedback and electronic beeps. (Listening to it now reminds me of a story that my friend Derek Walmsley, the Reviews Editor of WIRE magazine, told me: once when he was working in MVC in Notting Hill someone played a VIC 20 cassette on the shop stereo, inspiring one far out IDM fan customer to enquire what it was and if he could buy it.) ‘Hit By A Rock’ is Cabaret Voltaire gone cosmic, while the version of ‘United’ is merely the tape of the single version played so quickly it loses any kind of sense. Admittedly ‘AB/7A’ is a glistening slice of electro, which weirdly wouldn’t sound out of place played in a modernist place of worship such as Liverpool’s Metropolitan Cathedral or The Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, despite clearly nodding to everyone’s favourite Swedish disco/pop group. But mainly this album is the sound of collapse and abjection. The vivid burns unit horror of ‘Hamburger Lady’ – featuring everyday sounds of a hospital ward rendered in the most chilling way possible – may well be better known, but the real creeping terror of this album lies in the gothic ‘E-Coli’, the pure noise of ‘Walls Of Sound’ and sterile, clicking white hiss coupled with the covert recording of a male prostitute contained on ‘Valley Of Shadow Of Death’.

The intense lifestyle and philosophy of the group, and the fact his relationship with Tutti was collapsing, caught up with P-Orridge just before the album was recorded and he took a large overdose of mogadon before a gig. With this in mind ‘Weeping’, the child-like song co-written by the singer while recuperating on valium, is a particularly harrowing listen. The second CD contains nine live tracks recorded during 1978 (including a lively reboot of After Cease To Exist) as well as the 7” tracks ‘Five Knuckle Shuffle’ and ‘We Hate You Little Girls’, which shows if nothing else, that even during this grim year, P-Orridge didn’t entirely lose his sense of humour.

In recent years retrofuturism has become a well-worn subject that bands everywhere from We Were Promised Jetpacks and The Flaming Lips to Leyland Kirby and Erasure have delved into. It is usually a key subject mentioned when the music of artists such as Boards of Canada, Broadcast and Oneohtrix Point Never and other “hauntological” groups are being discussed. The growing popularity in the use of vintage synthesizers at the moment dovetails neatly into themes of looking back to more aspirational, hopeful times. But even back then Throbbing Gristle realised that the end product of an industrialized society wasn’t more leisure time for humans, merely their redundancy. The moronic complaint by Musicians Union types back then that synthesizers and electronic gadgetry were putting ‘real’ musos out of work were met by TG who seemed to be saying: Yes, we know. That is the point. D.o.A. seems intent on pitting human failure (‘Weeping’, ‘Hamburger Lady’) against machine success (‘IBM’, ‘Walls Of Sound’).

Throbbing Gristle’s third long player genuinely is nice in bits though. ‘Hot On The Heels Of Love’ is a straight up Italo disco number, albeit a very glacial one. It highlights Carter’s burgeoning abilities as a programmer and sees the initial experiments of subverting pop on tracks such as ‘United’ come full circle. With breathless vocals from Tutti, the track set the template for some of the pair’s excellent post-TG work together during the 80s. Another memorable Carter moment on the album is ‘Walkabout’, a glistening slice of Kraftwerkian techno, comprised of celestial arpeggios, stripped of any other recognizable industrial or disco elements, bar a bed of pulsating synth noise. (Carter’s ‘pop’ songs act like the film The Straight Story in the middle of David Lynch’s otherwise deranged career. These songs state, ‘Look, we can do pop music with the best of them – we just choose not to.’)

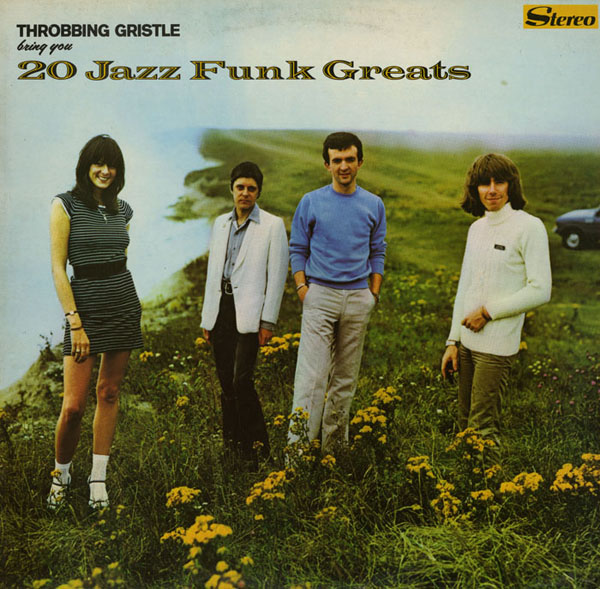

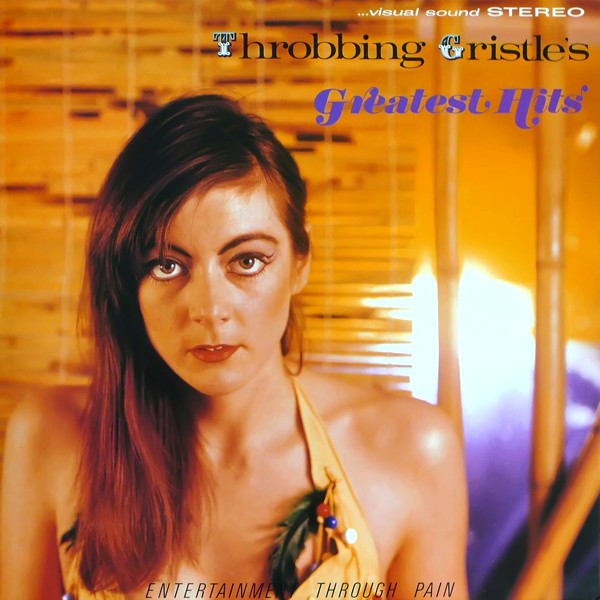

Aware that the band would, in all likelihood, snare a few unsuspecting punters into purchasing the album by the title and artwork alone, they went one step further and created in the opening title track a simulacrum of jazz funk. As Drew Daniel of Matmos says: ‘Chalking the sidewalk outline around the corpses of jazz and funk with heavy quotation marks, TG offer not jazz but “jazz”, not funk but “funk”.’ (There is more violently debased ‘jazz’ in the bass and vibes of ‘Tanith’, a P-Orridge track, and some unhinged “easy listening” in Carter track ‘Exotica’ for the hell of it as well.) It is only when you hear ‘Beachy Head’, however, an atmosphere of synthesized breezes, gull calls, guitars mimicking ships horns and deep bass drones of dread, that you become aware that there is more to the cover art than meets the eye.

The album has a dense binary star pairing at its centre, whose gravity holds everything in place, with ‘Persuasion’ as the primary force and ‘Convincing People’ as the companion. The latter track is about political control where the former is about personal control. ‘Persuasion’ crackles with power – specifically thanks to the tension between P-Orridge’s dirge like bass and sinister, procedural revelations of how he coerces people and Tutti’s insane bursts of resistant, squealing guitar noise. The song is no less powerful for it being a testament of Tutti’s ‘victory’. In literal terms, she had successfully left the singer for Carter by this point and not been persuaded to return to him – but in less literal terms, it is a battle of sonic strategies that she clearly ‘wins’.

Insidiously, the most distressing element to ‘Persuasion’ is like a funhouse mirror held up to the Serge Gainsbourg song ‘En Melody’. The funkiest track from his outstanding Histoire de Melody Nelson album is supposed to represent Serge having sex with his underage teenage conquest from Sunderland. In order to coax suitably erotic noises out of his lover Jane Birkin (who was playing the title role on the album), he took to tickling her causing her to laugh uncontrollably. It is only when this ‘laugh track’ is added to the sexually charged music that it takes on a different, more adult nature. Christopherson was responsible for covertly and overtly taping much of the spoken word content of TG’s albums. But in this instance it is a relatively innocent tape of a ten year old boy, whose laughs and squeals become transformed into something altogether more terrifying simply because of the musical context. The extra disc contains six live tracks recorded in Manchester’s The Factory venue in 1979, another taped at Northampton’s Guildhall, as well as the murky but furious 12” A side ‘Discipline – Manchester’ and the slightly less dynamic and no less clear B side ‘Discipline – Berlin’.

But it was to be their last album and they started as they began, flying by the seat of their combat pants, doing everything to throw obstacles in their own path, asking associate Stan Bingo to record the event and act as sound engineer, precisely because he’d never done it before and didn’t know what he was doing. But their gamble paid off and it remains a brilliantly weird album. They went out demanding nothing other than 100% clarity of vision from their fans. As P-Orridge intones: “You should always aim to be as skilful as the most professional of the government agencies. The way you live, structure, conceive and market what you do should be as well thought out as a government coup. It’s a campaign. It has nothing to do with art.” (This reissue contains the best of the extra discs, containing a number of rare live tracks such as ‘Auschwitz’ and ‘Devil’s Gateway’ as well as the single tracks ‘Subhuman’ and ‘Adrenalin’.)

But actually perhaps this photograph does add something to the story. It’s odd to see TG out of uniform but even in exotica mufti, they’re still instantly recognizable. The best outlier groups look like action figures of themselves – and this is as true of Sunn O))), Public Enemy, Slayer, Mayhem, Kraftwerk, CRASS and The Velvet Underground as it is of Throbbing Gristle. This is because they are complete aesthetic units, where nothing has been left to chance. It speaks of complete immersion, total control and unshakable vision. Also, why are they laughing? They are laughing because they are in a funny band. Admittedly, the humour is sometimes oblique, sometimes thin on the ground and sometimes too black for comfort, and sometimes they’re only laughing because otherwise they’d be crying, but it is quite obviously there. Of all the silly accusations that have been levelled at TG over the years, I haven’t read anything quite as daft as the suggestion that ‘We Hate You Little Girls’ is misogynist. I guess they’re not a band for literalists looking for a reason to get upset. Coming a close second for me is ‘Subhuman’, which isn’t even in their top three of ostensibly offensive songs about concentration camps.

I personally don’t think that TG are, or were, Nazis or Gypsy killers or paedophiles or “wreckers of civilization”, and I don’t think most other people do either; at least they don’t when they stop and think about it. So if they’re not mocking little girls, gypsies, burn victims and suicidal coastal ramblers, where is all this scorn being directed? Could it be that it’s us? At the average buyer of so called ‘alternative’ music? That they’re simply laughing at people who do nothing to resist their pre-determined roles in a post industrial, late capitalist society? An uncomfortable suggestion given that no one likes to be mocked in public.

In a rare moment of warm heartedness towards the end of their career (or weakness, if you listen to P-Orridge), they took advice to record a song with a positive message – leading to ‘Don’t Do As You’re Told, Do As You Think’. (P-Orridge later recalled the genesis of the song: “To be honest I think this is the weakest vocal track and lyric [on Heathen Earth]. Someone, a journalist or Sleazy, or both, suggested we should have a “positive” message! Ugh! Certainly Sleazy persuaded me to try and this is the resultant track. I still find it embarrassing and wish I’d never listened to him. It would have been better as an instrumental. Ah well…”)

On this one song, it is spelled out for you. Throbbing Gristle were one of the few groups to treat you like an intelligent adult; if you return the favour you can see them for what they were: incisive satirists, great artists, brilliant entertainers, terrible musicians making peerlessly superb music… However, if you choose not to return the favour, all you are left with is ugly, vicious noise.

Some Good TG Reading:

Wreckers Of Civilisation: The Story Of COUM Transmissions And Throbbing Gristle by Simon Ford

Throbbing Gristle’s 24 Jazz Funk Greats (33 1/3) by Drew Daniel