For details of a free literary event including a reading from the book by Peter Doggett at Foyles on Charring Cross Road tonight, go to the end of the feature.

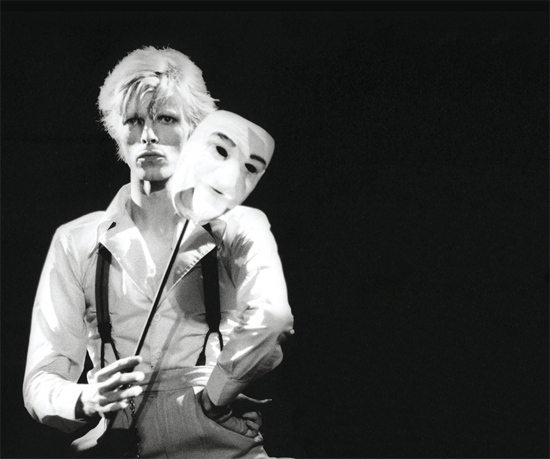

The Unmaking of a Star #3: Cocaine and the Kabbalah

I just wish Dave would get himself sorted fucking out. He’s totally confused, that lad… I just wish he could be in this room, right now, sat here, so I could kick some sense into him.

Mick Ronson, 1975

Cocaine was the fuel of the music industry in the seventies. Audiences were still more likely to have smoked dope, or swallowed the ‘downers’ known as Mandrax in Britain and Quaaludes in the USA. Rock stars in search of a cure for the burdening necessity of sleep could rely on the artificial energy of amphetamines (with the attendant risk of psychosis). Where casual sex and the dance floor collided, there was likely to be amyl nitrate or, in America, PCP (alias angel dust). But the drug that kept rock ’n’ roll buzzing, sealing deals, deadening sensibilities and providing a false sense of bravado and creative achievement, was cocaine. Bowie’s arrival in America in 1974 coincided neatly with the rapid growth of the

cocaine-producing industry in Colombia, which within two years had corrupted that nation’s political structure to such an extent that the most notorious traffi ckers (such as Pablo Escobar Gaviria) were effectively beyond prosecution. Like heroin at the start of the decade, cocaine flooded into America, despite the efforts of federal law-enforcement agencies to stem the tide.

Bowie was, and has been, more candid about his drug use during this period than most of his contemporaries, and various associates have fleshed out the picture. ‘I’ve had short flirtations with smack and things,’ he told Cameron Crowe in 1975, ‘but it was only for the mystery and the enigma. I like fast drugs. I hate anything that slows me down.’ So open was his drug use that the normally bland British pop newspaper Record Mirror felt safe in 1975 to describe Bowie as ‘old vacuum-cleaner nose’. His girlfriend in 1974/75, Ava Cherry, recounted that ‘David has an extreme personality, so his capacity [for cocaine] was much greater than anyone else’s.’ ‘I’d found a soulmate in this drug,’ Bowie told Paul Du Noyer in 2002. ‘Well, speed [amphetamines] as well, actually. The combination.’ The drugs scarred his personal relationships, twisted his view of himself and the world, and sometimes delayed recording sessions, as Bowie waited for his dealer to arrive. As live tapes from 1974 demonstrated, they also had a profound effect on his vocal range. Yet the effect on his creativity was minimal: cocaine took

its toll on his internal logic, not his abilities to make music.

‘Give cocaine to a man already wise,’ wrote occultist Aleister Crowley in 1917, ‘[and] if he be really master of himself, it will do him no harm. Alas! the power of the drug diminishes with fearful pace. The doses wax; the pleasures wane. Side-issues, invisible at first, arise; they are like devils with flaming pitchforks in their hands.’ Bowie’s ‘side-issues’ were rooted in his unsteady sense of identity; he talked later of being

haunted by his various characters, who were threatening him with

psychological oblivion. When he described the Thin White Duke of

‘Station To Station’, he was effectively condemning himself: ‘A very Aryan, fascist-type; a would-be romantic with absolutely no emotion at all but who spouted a lot of neo-romance.’ Michael Lippman, Bowie’s manager during 1975, said his client ‘can be very charming and friendly, and at the same time he can be very cold and self-centred’. Bowie, he added, wanted to rule the world.

It was not entirely helpful that a man who was bordering on cocaine psychosis should choose to immerse himself in the occult enquiries that had exerted a more intellectual fascination over him five years earlier. The sense that his soul was at stake was exacerbated by the company he kept in New York at the start of 1975: Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page, a fellow Crowley aficionado; and occult film-maker Kenneth Anger. In March that year, he moved to Los Angeles, where he was reported to be drawing pentagrams on the wall, experimenting with the pack of Tarot cards that Crowley had created, chanting spells, making hexes, and testing and investigating the powers of the devil against those of the Jewish mystical system, the Kabbalah. He managed to survive the fi lming of The Man Who Fell To Earth by assuming the emotionally removed traits of his character in the movie. But back in California, as he tried to assemble a soundtrack for the film and also create the Station To Station album, he slipped back into a state of extreme instability. Michael Lippman remembered ‘dramatically erratic behaviour’ on Bowie’s part. ‘Everywhere I looked,’ the singer

explained to Angus MacKinnon in 1980, ‘demons of the future [were] on the battlegrounds of one’s emotional plane.’

That was the emotional landscape against which he wrote the songs

on Station To Station: in retrospect, it is surprising that the results were not more extreme. By the time the album was completed, Bowie was suffering severe, sometimes nearly continuous hallucinations, which ensured (perhaps fortunately) that his memories of this period remain sketchy. The impact on those around him was more immediate; when the singer left the Lippmans’ residence at the end of December (and quickly

launched a lawsuit against his recent protector), his traumatised manager could only express relief, coupled with fear at what might happen next. Bowie attributed his survival to an unnamed friend, who ‘pulled me off the settee one day, stood me in front of the mirror and said, “I’m walking out of your life because you’re not worth the effort”’. This jolted Bowie enough to propel him through a major tour, still flirting with the worst of

his curses, before he chose quite deliberately to crash-land in Berlin, and offload all his burdens, nightmare by painful nightmare.

STATION TO STATION (Bowie)

Recorded September–November 1975; Station To Station LP.

Much of The Man Who Fell To Earth was filmed in Albuquerque – the so-called ‘Duke city’. And it was there that David Bowie, who was unmistakably thin, and white, began to write a book of short stories entitled The Return of the Thin White Duke. It was, he explained, ‘partly autobiographical, mostly fiction, with a deal of magic in it’. Simultaneously, he was telling journalist Cameron Crowe: ‘I’ve decided to write my autobiography as a way of life. It may be a series of books.’

Or, as printed in Rolling Stone magazine at the time, it might be the briefest and most compressed of autobiographical fragments, which suggested he would have struggled to extend the entire narrative of his life beyond a thousand words.

Instead the Thin White Duke returned in this song, which it would

be easy to assume must therefore have been autobiographical. But

Bowie’s landscape was more oblique than that: not least because, in the tradition of ‘The Bewlay Brothers’, this was a song with lyrics that suggested more than they revealed, as if they had been written in a strictly personal code – an occult language, then, in every sense of the adjective.

Even if Bowie saw himself as the Thin White Duke, another duke

was at the heart of the action: Prospero, the rightful Duke of Milan, exiled on an island in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. It is Prospero whom Bowie misquotes in the song, Shakespeare’s original line being: ‘We are such stuff as dreams are made on.’ (The same speech refers, as does Bowie, to ‘thin air’.) Prospero, like Bowie’s Duke, is a master of magic, who can command the elements while ‘lost in my [magic] circle’. And he can also cast a spell – throwing darts,* perhaps – over lovers’ eyes, as he does with his daughter Miranda and her paramour, Ferdinand, during the course of the play.

Shakespeare, however, was only one source for a song rich in

borrowed imagery. This ranged from the vaguely ridiculous (compare Bowie’s drinking stanza to the chorus from The Student Prince made famous by Mario Lanza) to the deliberately hidden (or occult). Only the keenest of occult scholars would have recognised White Stains as the title of a slim volume of verse by Aleister Crowley (Bowie may have owned a copy as early as 1969, as there were apparent allusions to Crowley’s poem ‘Contra Conjugium TTB’ in ‘Cygnet Committee’). Likewise, few amongst Bowie’s audience in 1976 would have been familiar with the Jewish mystical system of the Kabbalah, with its septhiroth (or stations, if you like) separating Kether (the realm of spiritual transcendence; the Crown of Creation, as the rock band

Jeff erson Airplane put it) from Malkuth (the conduit for divine revelation to reach the physical world). ‘All the references within the piece are to do with the Kabbalah,’ Bowie claimed in 1997, not entirely accurately. Then there was the strange reference to the European canon (or, at a stretch, ‘cannon’), which was a pretentious way of summarising Bowie’s interest in Brechtian theatre and Kraftwerk; and the final choruses of the song, which (canon aside) seemed to offer an account of all-powerful love (nature unknown).

With that, the lyrics came full circle, from the Duke’s command

over lovers to the lovers’ loss of control over themselves. In a song this esoteric, it may or may not be significant that Aleister Crowley’s pack of Tarot cards represented Art and Lovers as complementary icons; that a dart, or arrow, was a symbol of direction revealing the dynamic of the True Will; that the Kabbalistic Tree of Life referred to a ‘heavenly bow and arrow’… almost every line could be glossed and interpreted, without coming any closer to Bowie’s intentions.

Take a step back, and consider the basic themes: magic, and the arts of legendary magicians, fictional and otherwise; the Kabbalah’s mystical account of progress from Kether to Malkuth; love; cocaine. Just as ‘Quicksand’ offered a catalogue** of avenues open to the inquisitive imagination of David Bowie circa 1971, so ‘Station To Station’ presented a more confused (because Bowie was more confused) medley of the themes that were haunting his nightmares in the final weeks of 1975. Yet he could surely not have expected his fans to deduce more from the lyrics than that he had invented a new character, called the Thin White Duke, who took cocaine.

What rescued ‘Station To Station’ from utter obscurity and his audience from alienation was the music. The song comprised a complex arrangement of fragments in the vein of a progressive rock suite (imagine something by early-seventies Genesis or mid-seventies Jethro Tull), connected by the sonic impact of Bowie’s remarkable 1975/76 band, and the mannered flexibility of his voice. Like the howls of wind that opened Van Der Graaf Generator’s ‘Darkness’ a few years earlier, the eerie train effects that signalled the beginning of the Station To Station album were both symbolic and visceral. The train (created by guitar with flangers/phaser and delayeff ects) ran from right to left across the stereo divide before disappearing into a tunnel with a howl of feedback. Gradually the band awoke: percussion knocking, a keyboard stabbing repeated chords in and out of key, bass, drums, a second keyboard, and finally a gargantuan atonal guitar riff (played by Bowie and Earl Slick with syncopated accents across three bars in 4/4 and one in 2/4). This train was no express, bound for glory; its lumbering progress suggested a force too evil to stop.

More than three minutes after the album began, Bowie finally made

his entrance alongside the Duke, still unwilling to settle comfortably into a recognisable key signature. The uneasy relationship between the two identities was mirrored by the way in which their voices were sometimes in orthodox harmony, sometimes in unison, sometimes (as when surveying the trail from Kether to Malkuth) a whole octave apart. Bowie announced his arrival in double-voice, one echoed and tired, the other almost hysterical, as if under attack from the wicked one’s fiery darts.

A thud of drums signalled a change, of tempo, key (now strictly

orthodox) and intentions: Bowie had entered the landscape of mountains and sunbirds, prodded by a burbling electric guitar. After three lines (accompanying the drinking episode) built around the slowest of turnarounds (like a train that had reached the end of its journey), there was finally the joyous relief of cocaine, and love. Here was Bowie’s first nod of recognition to the so-called ‘motorik’ sound of Krautrock, as the ominous Wagnerian strains of the early segments of the song were succeeded by the propulsive dance rhythms of the finale. Only

a churl would have worried that the theme of this cathartic moment was that it was too late – suggesting that the spiritual journey might not lead to salvation.

- There is a long tradition of darts, or arrows, being used as a weapon in combat between deities, or between God and the devil: see, for example, St Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians (6:16), in which he off ers ‘the shield of faith’ to ‘quench all the fiery

darts of the wicked one’.

** The missing link between these two songs, in thematic terms, was provided by an artist in whose work Bowie had immersed himself around 1974: Peter Hammill. ‘(In The) Black Room’ from his 1973 album Chameleon In The Shadow Of The Night was preoccupied with various adventures of the spirit, from the Tarot and religious belief to psychedelic drugs.

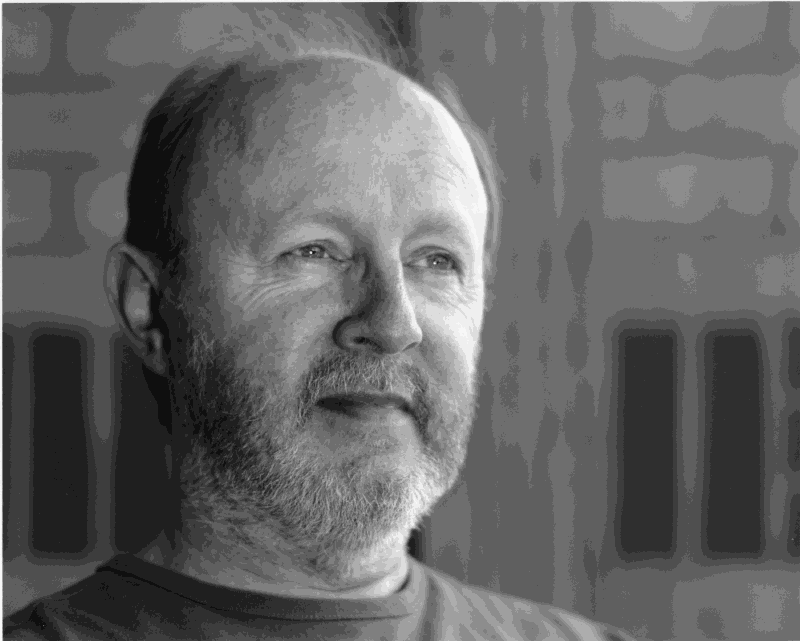

Peter Doggett

25th October 2011 6:30pm – 7:30pm Charing Cross Road Literary Event, Signing, Free Event

Peter Doggett appears at Foyles to discuss The Man Who Sold The World, his new book on David Bowie, which explores the place of albums such as Hunky Dory, Diamond Dogs and Scary Monsters in the cultural and political turmoil of the 1970s. His detailed analysis of every song on every album reveals the diverse sources of inspiration for Bowie’s music and his influence in turn on countless other musicians, but Doggett also looks at how Bowie expressed his attitudes to wider themes such as shifting notions of gender identity and the West’s uncertainty in a time of oil shortages and terrorism.

Peter Doggett has been writing about popular music and social and cultural history for more than thirty years. His books include, You Never Give Me Your Money, a study of the Beatles’ break-up and its traumatic aftermath, and There’s A Riot Going On, his history of rock music’s collision with revolutionary politics.

And if you come a little early, you’ll be treated to a soundtrack of David Bowie rarities.

Originally published in 2011