It’s September 16th, 1963 and John Cale is walking onto the stage of a television studio in New York City. "That was one repressed individual," recalls the older, less repressed John Cale over the phone from his studio in Los Angeles, nearly half a century later, "Very uptight." Back in 1963, Cale in a dark velour suit jacket and tie takes a seat next to the show’s host, Garry Moore and whispers into his ear, "I performed in a concert that lasted eighteen hours." The point of the show was that the four panellists had to work out the guest’s ‘secret’ from a series of yes and no questions.

"Does it have anything to do with endurance?" asks former Miss America, Bess Myerson.

As a student at Goldsmiths College, in London, Cale had organised a festival of new music and had brief text scores published in George Maciunas’s Fluxus Preview Review. He had made friends with Humphrey Searle, who had been a student of Anton Webern’s in Vienna and composed an opera based on Gogol’s Diary of a Madman; as well as Cornelius Cardew, who had performed in the British premiere of Pierre Boulez’s groundbreaking work Le Marteau Sans Maitre and served as assistant to Karlheinz Stockhausen. "That whole experience was like opening up a Pandora’s box for me," he recalls of the time. "They didn’t like it at Goldsmiths in the end. No, they thought I should have been doing what I should have been doing."

Having won a scholarship to the Tanglewood Institute in Boston, Cale started writing to John Cage, determined to work with the man he considered the "most interesting composer" of the era. Cage’s book, Silence, had broken down for Cale, "this Welsh Presbyterian barrier that I had in my head. I mean there was life after religion!"

And so it was that on the evening of September 9th, 1963, Cale found himself part of a relay team of pianists (alongside composers Christian Woff, David Tudor, James Tenney, Philip Corner, and Cage himself) taking part in the first ever performance of a work written by Erik Satie towards the end of the nineteenth century called Vexations. The score consists of just one page of notes, with instructions that it is to be repeated 840 times.

"Is there any reason why he would say that?" asks Garry Moore in a television studio in 1963, "What would move a man to say that you must play it 840 times?"

"I’ve no idea," Cale replied.

"Mr. Cale, you have a will of iron."

Cale recalls working with Cage fondly. He was, he says, "Very funny. Giggly." Apart from anything else, it was a means of escape from the "rigidity" of the serial system of composition then dominant in Europe. Later, Cale would work with La Monte Young, founder of the minimalist school of composition, in his Theatre of Eternal Music. Young’s work could last even longer than the eighteen hours of Vexations. In theory, endlessly, without beginning or end. "He took some of Cage’s things and pushed them further," says Cale. The oneiric drones of Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music would prove to have a profound influence on some of Cale’s subsequent work with the Velvet Underground.

Still, Cale has no regrets about leaving the world of modern composition behind. He never wishes the world saw him less as a rockstar and more as a great composer. "Something about having a body of a hundred musicians and performing a piece for, like, twenty minutes, thirty minutes or whatever; I think recording has really spoilt all that for me. Recording studios," he tells me, "show another dimension."

Forty-eight years after he whispered his secret in the ear of Garry Moore in New York City, Cale will admit that he still has his secrets. He can still be secretive sometimes. At the end of the 1990s, Cale published his autobiography, What’s Welsh for Zen? A French translation was published earlier this year. "When I think about some of the things that I wrote in there. I’ve come up with a lot of different angles on what it meant. There’s a lot of stuff that’s gone on since then that can be addressed, but” (he pauses, as if reflecting on some particular grievance from the last decade or so) "I’d rather do it through songs."

I’ve interrupted Cale in the midst of putting the finishing touches to his new album, due out in February. Most of the songs were written whilst touring ("I’ve been travelling a lot") and developed little by little on the road. In the meantime, there’s a teaser EP out now on Domino imprint Double Six, Extra Playful, five tracks of fuzz pedals, backwards guitars, and clipped drum loops. There’s a curiously contradictory mood to the songs, at once reflective and forward-looking, "Say hello to the future, and goodbye to the past" he sings on the propulsive opening track, ‘Catastrofuk’. "That’s really how relationships go," he tells me. "You terminate a relationship for whatever reason, and you sort of say, that’s that, and let’s move on."

The centrepiece is a track called ‘Hey Ray’ which sees Cale reminiscing about his early days in New York in the 60s. The ‘Ray’ addressed by the title is mail art pioneer, Ray Johnson, an associate of John Cage and Merce Cunningham from Black Mountain College. "He was the first guy I met when I arrived in New York. He was one of these artists who was very reclusive. He’d never call you, you couldn’t call him. He would just send you mail that would contain all this bric-a-brac, and you’d tip the envelope out on the table and there would be a myriad bits of cuttings, bits of cardboard, objects, whatever. You’d never hear from him for months, and then all of a sudden you’d get an envelope." Juxtaposed with exhortations to Johnson that he was "driving me crazy", Cale mulls over "all those quirky things about the 60s that I remember" over a hip hop beat and scrapings of scroggy guitar noise.

"…1964: Castro’s up in Harlem. 1965: Their having a riot. 1966: The writing’s on the wall…"

It’s the 23rd of June 1966, and the Velvet Underground are playing as part of Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable at Poor Richards in Chicago. Factory regulars, Gerard Malanga and Ingrid Superstar are dancing in black tops, arms flailing wildly, before kaleidoscopes of coloured light. Somewhere in the distance, as if buried under smoke and lights, faint images form Warhol’s films flicker, faces gazing out of the walls accusingly. From the speakers comes the hauntingly melancholy Mitteleuropean vowels of Christa Päffgen, the Cologne-born fashion model who had played a walk-on role in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and changed her name to Nico: "I find it hard, to believe you don’t know…"

Cale wasn’t keen on Nico singing with the band initially. They’d had "a lot of struggle with having other female members in the band, and it always had ended up as a competition between Lou and I as to who was going to get the girl." Then here comes Andy with this girl who was deaf in one ear and could hardly keep pitch half the time. "Lou and I were sort of startled. Moe didn’t know what to make of it. And Sterling was harumphing . . . But, y’know, after a little bit, you got to understand Andy, and that was really pure Andy. Everybody suddenly started looking at us in a different way."

Years later, working with Nico again on her quartet of solo albums from the early 70s, Cale recalls, "she was slowly becoming more and more dependent." Nico was a heroin addict from the early 70s until shortly before her death in 1988. "So there was a window of opportunity you knew you had to deal with." Each record seemed to get somehow starker, bleaker than the last; culminating in The End, an album which, with its bells, its rogue synths, its winsome childlike choruses, would not sound out of place as the soundtrack to an Italian horror film. "She sort of brought herself around to it, generally. We went into the studio at two, she showed up at five and then we could work until about eleven. She just got on with it. You never knew if she was going to be happy or depressed."

As you might imagine, Warhol was never the typical band manager to the Velvets. "You didn’t think of him as the controller of it," says Cale. "He would let us get on with whatever we wanted to get on with." But there were things: he would give Lou titles for songs. "Here’s fourteen titles, write songs about them. And Lou was perfectly happy. Give him a project, he’ll focus." But if there was one moment, when Cale really started to understand Andy’s way of thinking, it was that day he was sitting around at the Factory in 1966 with Gerard Malanga, when Andy came back from his doctor’s appointment. "He called me over and showed me: this is the album cover." The magazines in the waiting room at the surgery had been full of ads for pharmaceuticals companies. The one that had caught Andy’s eye featured an image of a banana which the reader could pull down to reveal a list of all the vitamins found in a banana. "He said what do you think of this as an album cover? I thought it was amazing."

It’s April 24th, 1977, and Cale and his band are onstage at The Greyhound in Croydon. At an agreed moment, halfway through his cover of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, a roadie slides a dead chicken onto the stage on a wooden platter. Cale starts swinging the chicken round and round in the air, and then decapitates it before a horrified crowd. Blood spurting everywhere, he throws the head into the crowd. Everyone stops dancing. The rest of the band walk off stage in disgust. "That was when you got gobbed on a lot," says Cale, by way of explanation. "So you know, after a while, you’ve done a whole tour of England and you’ve been gobbed on a lot, you come to Croydon and you see all those guys with chains and everything else. Here’s something to think about." In his autobiography, Cale describes it as "the most effective show-stopper I ever came up with."

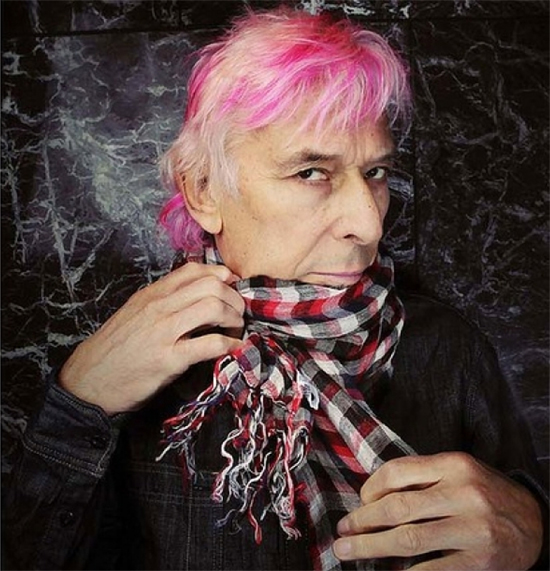

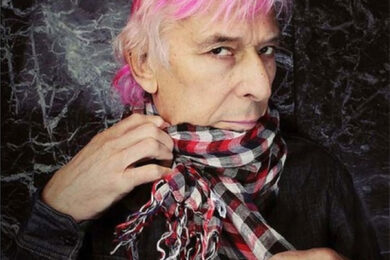

It was around the time that Cale had taken to wearing a hockey mask during shows. "We constructed the shows around that. There were layers. There was shades, then there was the scarf over the top with the metal designs, then over that there was the ski mask, and then on top of that came the mask . . . So there was a progressive unveiling." Five years later, supernatural serial killer, Jason Vorhees would start wearing a similar hockey mask to massacre the kids at Camp Crystal Lake in the Friday The 13th films. "I wonder what took him so long," Cale remarks, wryly.

"Do you think they were ripping off your act?"

"No."

After producing Patti Smith’s Horses in 1975, Cale had found himself at the centre of the burgeoning punk scene in America. Looking back now, he says he thinks that the slightly later bands from Los Angeles were really much more "ferocious" than the New York groups playing at CBGBs. "In LA the difference between the rich and the poor was far greater." This disparity, he tells me, "stirred up a lot of animosity." He remembers Vietnam veterans coming to the shows at the time, and wanting to take him back to their home after the show to give him presents, "and I’d say, well, what is it? And they say, it’s an original, genuine German Luger. And I thought, well, later . . ."

In an interview with Popshifter from a couple of years ago, Cale’s percussionist and backing singer from that period, Deerfrance, recalls, "John would attract a very specific kind of audience. Even during those dark days in the late 70s he could attract the strangest of the strange. The front row would be filled with people in wheelchairs, people cutting themselves. Backstage would be even more interesting. John could hold his own with crazies and geniuses and we met them all along the way."

"How do you think of that time now?" I ask Cale.

"Just a lot of fun."

On the day I interviewed John Cale, four men were trapped in a mine at the Gleision Colliery, near Cilybebyll in Pontardawe, Swansea. It’s about a twenty minute drive down the Cwmamman Road from where Cale was born and spent the first eighteen years of his life, in the small mining town of Garnant, at the foot of the Brecon Beacons. Cale’s father worked in the local anthracite coal mine. In his autobiography, he describes the place as, "a strange, remote, some said mystical land . . . rich in the Arthurian legends." Since writing that passage, he tells me, "I’ve come up with a lot of different angles on what it meant. Because that thing about growing up in Wales in that environment, morphs over time. And some of the things that are there – none of its untrue – it’s just that there are several other aspects that sort of flesh it out for me."

Interviewed by Miranda Sawyer for the BBC’s Culture Show in 2009, Cale admitted that he still felt that he hadn’t fulfilled all of his ambitions, all of his potential. I ask him if he still feels that way, and what ambitions he felt he still had to fulfil. "Well, to write better songs," he says. "I mean, as soon as I’ve finished with a song, it’s over, and I’ve got to find another hook that I like another groove that I like. There’s lots out there. I need to grab them."