French filmmaker Chris Marker is probably best known for a famous short called La Jetée (1962), a time travelling fable which was the inspiration for 12 Monkeys, among other things. This little gem was, for budgetary reasons, composed almost entirely of still photographs and narration, a surprisingly effective set up. People often forget in this age of CGI and 3D that when it comes to sci-fi, the less you show the better. Even fried by years of TV, your imagination is still pretty good at filling in the blanks.

Marker’s real specialty however was in ‘essay films’ such as A Grin Without A Cat (Le Fond de l’air est rouge, 1972), an epic treatise on the seeming demise of the New Left in Europe after the failures of 1968. But even in these films, made up mostly of archive footage, the spectre of fiction always has its way of intruding, much like the frequent appearance of cats and owls, Marker’s favourite animals. It was the very subject of documentary truth which became a central theme of one of his best films, Sans Soleil (1983).

Sans Soleil is ostensibly a kind of travelogue made by filmmaker Sandor Krasna. But instead of standard narration, an unnamed female voice recounts letters sent to her by Krasna about his travels. The footage jumps from Iceland to Guinea-Bissau to Japan to San Francisco with the nimbleness of Krasna’s stream-of-consciousness musings, which touch on post-colonialism, torture porn, animism, war and the function of memory. Some of these observations are profound, some a bit pretentious, but they’re all pleasantly conversational, never telling you what to think. This is partly because they’re delivered second-hand by a dispassionate intermediary, but also because they’re so fragmentary and open-ended, unlike the structured, debate-team arguments we’ve come to expect from documentary.

But what make the film so extraordinary are its images. At one point the film refers to a passage by the Japanese writer Sei Shōnagon, who talks about compiling arbitrary lists like "things that quicken the heart”. If there’s one thing that links all these disparate images, it’s this kind of stirring, unsettling quality they all have.

This is despite the fact that the original footage focuses mostly on subject matter which is not inherently beautiful: people sleeping on trains, advertisements, horror film stills and kitschy cat sculptures. If you’re going to make a film that is more or less carried by imagery, rather than plot, the temptation is to go big, to focus on panoramic shots of nature or the sublime terror of the industrial ‘second-nature’ we’ve constructed around us (as in Koyaanisqatsi or Baraka, for example). But instead of the macro, Marker goes for the micro, the mundane, always focusing on humans and their strange habits.

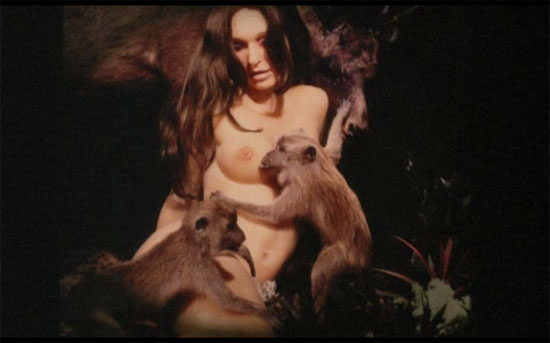

In this way, Sans Soleil bears a strange relation to the Mondo films of the 70s. Mondo films were Italian exploitation documentaries which showed a stream of tangentially related, bizarre customs from around the world (all a thinly veiled excuse to see native boobs and real blood). But after the first installment, Mondo Cane, they were mostly phony – either the narrator was lying about what the footage depicted, or the footage itself was staged with actors. San Soleil also focuses on the weird and the titillating (taxidermied animals in sex poses, an animatronic JFK in a shopping mall) but while the Mondo films describe these customs with sensationalism and innuendo, Marker explains what he sees with the curiosity and empathy of an anthropologist.

But San Soleil also has an uneasy relationship with truth. In fact, it undermines itself at every opportunity. For starters, Sandor and nearly all of his named collaborators, including the brother who did the Radiophonic Workshop-esque ambient soundrack, don’t exist (Marker did nearly everything). Then there’s the fact that 16mm handhelds don’t have synch sound which means that all the diegetic noises and incidental music you hear is at best artificially synched if not taken from somewhere else entirely. Then there are more general questions about what is stock footage and what is original. Are scenes separated by geography also separated by years?

This is exacerbated by the fact that Marker frequently draws attention to the structure of the film itself. The film begins with a grainy image of Icelandic children which Sandor explains he couldn’t link to anything but “…one day I’ll have to put it at the beginning of a film with a lot of black leader”. He laments how the subjects of most films don’t look into the camera, then repeatedly breaks the fourth wall on purpose. He even talks about what footage to use where and how digital filters might make historical footage less sentimental.

The effect is similar to that of a recent YouTube parody of Adam Curtis (a film essayist no doubt influenced by Marker) which consisted of a series of random stock clips played while an impersonator explained “This is the story of a documentary filmmaker who made lauded programs for the BBC, and how he finally proved that style always triumphs over substance… He realised that it did not matter what footage he used, so long as he changed the shots so bewilderingly fast that the audience would miss the gap between argument and conclusion…”

We are so easily carried away by films but all you have to do is explain a film’s techniques and the whole artifice becomes opaque and constructed – the authoritative voice and truth-telling window of the screen short circuit, revealing just a man pulling levers behind a curtain. It’s interesting how fragile the bond of trust between filmmaker and audience can be.

When Orson Welles similarly got self-referential in F for Fake he was playing an elaborate game with the audience (if you ever wondered what the human embodiment of ‘lying’ looks like, it’s a bearded Orson Welles wearing a fashion cape!) but Marker’s intention is to make you think critically – not distrust inherently all you see.

For once in a film of this ilk, the incredibly pretentious premise serves an important purpose. If there is a point to all this, then it’s to draw your attention to how images can come to supplant memory, and more importantly, history, if we are not careful. The Tokyo we see in San Soleil, in the early ’80s, was like a vision of The West’s future – part Blade Runner, part Baudrillard – and this future was dominated by timeless consumerist images which seemed to mask the violence, war and history lying just beneath the surface.

We seem hard-wired to want to believe in the images we see on film, especially those labelled ‘documentary’. But far from capturing the truth, films obscure complex narratives and are easily manipulated through editing and, of course, words. Sans Soleil is a political filmmaker struggling against the potential of his medium to be authoritative and propagandist. But his solution, the combination of dream-like images and fractured prose, is still pretty seductive – kind of like hypnotizing you to wake up.

Sans Soleil,La jetée and Level Five are all available now on DVD.