"Edinburgh is full of comedians who want to be TV presenters," says veteran stand-up Scott Capurro with a sweet, sunny smile. "Why don’t you just cut yourself, you self-loathing cunts…?"

August in Scotland. The world’s largest arts festival: 258 venues, over 2,500 shows, around 1.8 million tickets sold. Imagine 10 back-to-back Glastonburys spread across 25 days, with a vast army of artists and punters all kettled within a few square miles in Edinburgh. Actually, the seething urban carnival atmosphere of the Scottish capital’s fabled Fringe Festival feels more like South By South West, the annual music industry jamboree in Austin, Texas. Every last possible basement bar, church hall, cobbled courtyard and converted car park has been pressed into service as a round-the-clock performance space. Welcome to North By North East.

Pushing past the endless waves of grinning jugglers, trying-too-hard buskers and jaded London media whores, your Quietus correspondent is on a mission to find the sick, dirty, dark heart of the Fringe. This means avoiding the zany-haired Australians and sold-out posh-boy stand-ups, and instead seeking out veteran provocateurs like the London-based San Franciscan comic Capurro, whose latest Fringe show Who Are The Jocks? weaves tender reflections on his mother’s death around button-pushing jokes about incest, the Columbine massacre and rough gay sex. Great stuff.

In short, I want to leave Edinburgh feeling jolted, challenged, disgusted, disturbed, violated even. Why? Because that is the job of all great art. Good taste has nothing to do with it. To be honest, this is also a sentimental journey, a doomed search for long-lost youth. When I first visited the Fringe as an idealistic teenager in the mid 1980s, the ‘alternative’ comedy boom was still in its post-punk phase: edgy, experimental, spiky and surreal. It was often politically worthy too, of course, but equally likely to challenge taboos and make you work a little harder for your cosy liberal opinions.

Since then, live comedy has been through its own Britpop-style explosion, making the metaphorical leap from indie to major, underground to mainstream. Stand-up is now a huge industry, with the Fringe as one of its key shop windows. Increasingly aimed at a primetime family audience, most of the aspiring comics in Edinburgh are plainly being groomed for their own BBC Three series or Radio 4 panel show. In the future, everyone will be famous on Dave for 15 minutes. Every day.

Mooching around the Fringe, benign blandness starts to look like the new comedy business model. Ever since those notorious outbursts by Russell Brand and Frankie Boyle united left and right alike in mock shock, boyish cheek and wholesome good taste have become depressingly marketable. As ever, the stupid and the prudish ruin things for the rest of us. If stand-up ever truly became the ‘new rock & roll’, arena-filling gag merchants like Michael McIntyre would be Coldplay. Such is the banality of evil.

McIntyre is not even playing this year’s Fringe, but he still proves too big a target for some of comedy’s old guard. The original shock jock of Scottish stand-up, Jerry Sadowitz skewers his family-friendly rivals between bracingly offensive jokes about "spastics", the recent London riots, Anders Brevik and Milly Dowler. In his show Comedian, Magician, Psychopath, the diabolical Mr Punch lookalike dares you not to laugh at his breathtaking bad taste. There is definitely something exhilarating about Sadowitz’s indiscriminate machine-gun cruelty, but plenty of calculated provocation too. He undoubtedly belongs on the dark side of the Fringe, but a little more insight into the anger and self-loathing behind his savage nihilism might have made a more genuinely edgy show.

Also dropping scornful asides about McIntyre is Quietus favourite Stewart Lee, who sold out his entire Edinburgh run weeks in advance despite fielding a work-in-progress show that is still rough around the edges – a drawback he smartly turns into fuel for his cranky, world-weary, perennially disappointed stage persona. Besides, even a half-baked Lee set contains more inspired tangents and surreal imaginative leaps than most polished arena-comic shows. Teasing out elliptical links between Scooby Doo, Osama Bin Laden and Planet of the Apes, the deadpan comedy Dadaist also reads out some ferociously negative quotes from his online critics, and uses a throwaway line about anal rape to attack one of his familiar targets, Frankie Boyle.

In fairness, I am not convinced Lee and Boyle are really so far apart in comic technique. Both inhabit exaggerated self-portraits that accentuate the bitter, sour, nihilistic side of their characters. Each understands that tragedy and comedy are very close and often overlap. Both are literate, politically engaged intellectuals with an unashamedly arrogant contempt for their lazy, careerist peers. In Edinburgh, Lee’s tirade against Helena Bonham Carter’s Tory views is almost as remorseless as one of Boyle’s bilious routines, albeit more rapier than bludgeon. But at his best, Lee remains the Charlie Kaufman of stand-up, deconstructing his own meta-comic riffs even as they unfold on stage, a Brechtian anti-comedian caught in an endless Moebius strip of self-referential irony.

Like Lee, several big-name comics are using this year’s Fringe as a springboard for their autumn tours. Down-to-earth populist Dave Gorman is arguably on the Coldplay side of the comedy fence, but his slick PowerPoint Demonstration show is effortlessly enjoyable and oddly reminiscent of Lee’s in places, notably in the extended routines based on quotes harvested from the internet. Gorman’s bloke-next-door niceness sometimes blunts his wit, but his Twitter feud with Jim Davidson and his musical poem about the French company supplying flags for the London Olympics are both terrific touches.

Comedy at the Fringe may be dominated by stand-up, but many of the more adventurous acts combine traditional jokes with musical and physical theatre, mime and magic, props and puppets. The sketches performed by the young, mask-wearing team Late Night Gimp Fight are typically undergraduate hit-and-miss affairs, many featuring the kind of sex-and-violence cop-out punchlines that Stewart Lee scornfully mocks. But the Gimps stand out thanks to a witty selection of doctored video clips and musical numbers, including a brilliant chorus of fluorescent toilet seats singing Stand By Me.

Also pushing the limits of sketch comedy is the US duo The Pajama Men, whose quickfire show In the Middle of No One is a surreal sci-fi fantasy featuring a dazzling range of accents and characters. It’s essentially gentle stuff, but with agreeably absurd overtones in the Monty Python and Mighty Boosh vein. Another impressive one-off is The Boy With Tape On His Face, aka the London-based New Zealander Sam Wills, a hyperactive performer who makes great use of music, props and audience participation in his wordless Edinburgh show. Gimmicky and repetitive, but still great fun.

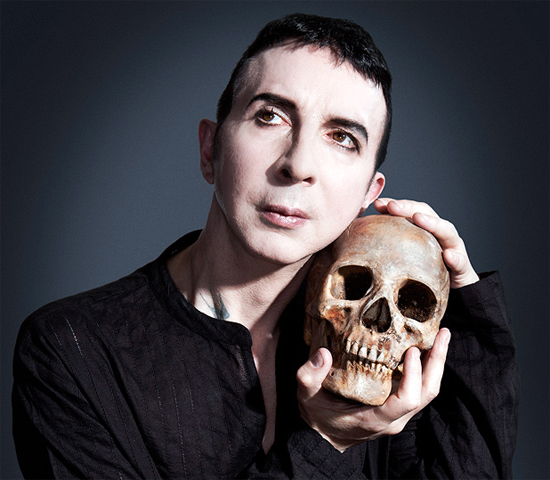

The Fringe began as a drama festival, and straight plays remains the only statistical rival to comedy in the Edinburgh listings. Making a brief diversion from humour in my quest for dirt and darkness, I find plenty in Mark Ravenhill’s haunting one-man musical Ten Plagues, starring Marc Almond as an eyewitness to the last great bubonic plague epidemic of 1665, which killed 100,000 Londoners. Southport’s answer to Serge Gainsbourg wears an elegant black skirt throughout, acquitting himself well with a complex sung-through libretto set to Conor Mitchell’s stridently modernist piano score.

Ravenhill does not overplay the AIDS parallels, but they are impossible to ignore in this carnal and sensual pageant, especially as he has been living with HIV for over a decade. He and Almond have also both recovered from life-or-death comas in recent years, which lends their poetic reflections on dead lovers and survivor’s guilt an extra emotional charge. With its smart use of back projection and sly final twist of audience participation, Ten Plagues is already a rave-reviewed sell-out and dead cert for London transfer after Edinburgh.

Usually a Fringe fixture, big-name American comics are thinner on the ground this year than usual. Even so, there are some reliable regulars in town, including Flight of the Conchords co-star Kristen Schaal and her stage partner Kurt Braunohler. Their nightly variety show Hot Tub is a ramshackle mix of surreal sketches and cheesy musical numbers, but with an enjoyably creepy and macabre edge. Making her first Edinburgh appearance in a decade, the Korean-American comic Margaret Cho is also great company. Her stand-up set Cho Dependent is packed with raunchy, scatological and occasionally eye-watering confessions from her polymorphous sex life. Life-affirming filth. Yay!

But easily the best US import I see at the Fringe is Neil Hamburger, a seedy stand-up raconteur with a bad attitude, a greasy combover and an ill-fitting Rat Pack suit. The foul-mouthed alter ego of Australian-born indie-rocker Gregg Turkington, Hamburger has recorded numerous albums, opened for Jack Black’s spoof band Tenacious D and even performed at rock festivals – indeed, he was bottled offstage at Reading last year for his abrasive anti-jokes about the disgusting antics of pop stars and celebrities. Respect. Onstage in Edinburgh, he is a pitiful piece of human wreckage, like Sir Les Patterson scripted by Samuel Beckett.

Hamburger’s Fringe show Discounted Entertainer is a one-man orgy of self-loathing and sick jokes, including probably the best gag ever written about being gang-raped by Crosby, Stills and Nash. He also winces and sobs with each disturbing punchline, as if compelled to deliver them by forces beyond his control. This is evil genius at work. With these queasy insights into a purgatorial parallel universe still ringing in my ears, I leave the world’s biggest arts festival feeling both revolted and cheered. However sanitised and commodified the Fringe may have become, it is oddly heartening to discover there is still some darkness on the edge of Edinburgh.