Alexandra Palace, that hulking great hunk of Victorian grandiosity, is suffering from an identity crisis. It thinks it’s still a mainstream entertainment centre, but logic dictates the opposite, perched, as the building is, atop a hill northwest of Tottenham. It boasts more inconvenient transport links than the O2 Arena, but somehow remains entirely more palatable. Maybe it’s the fact that you can see the former Millennium Dome, squatting to the left of the steroid-pumped cluster at Canary Wharf, from a pleasant vantage point up on the hill.

Maybe also it’s the fact that Ally Pally has retained the early kudos it gained as the first home of the BBC, who moved there in 1936. During the pre- and post-WWII years it was the home of public service broadcasting: it is a connection that seems fitting this weekend, as ATP (All Tomorrow’s Parties, the VU/Nico song, a tradition which I’ll Be Your Mirror neatly carries on) has become a kind of public service for those that crave mass participation, but want music of a higher quality, a greater devotion to sound in return for their (quite substantial amount of) hard-earned cash.

Like the December 2007 ATP, the curators are Portishead. The core three (Beth Gibbons, Geoff Barrow, Adrian Utley) are a band of thinkers – nay, over-thinkers – who don’t seem at home on a stage as big as this but thrive on it all the same. Their set is the only one that really fills the enormous Great Hall, a venue that has never really been regarded as a brilliant vessel for sound, and Doom in particular suffers from the lack of low-end. Without a deeper bass to prop him up, his complex hip hop backing (admittedly coming from a lone laptop) comes across with all the thump of a tinny ringtone.

By the time PJ Harvey arrives things improve. Barely visible in black against black, she of course plays her album, Let England Shake. That it is a [insert superlative here] album is not in doubt, but what of its live depiction? Harvey and band deliver it note-perfect, but it very nearly gets lost in the space, the sentiment almost segueing into the air like vapour – but not quite. The words are too powerful for that: These, these, these are the words. The words that maketh murder.

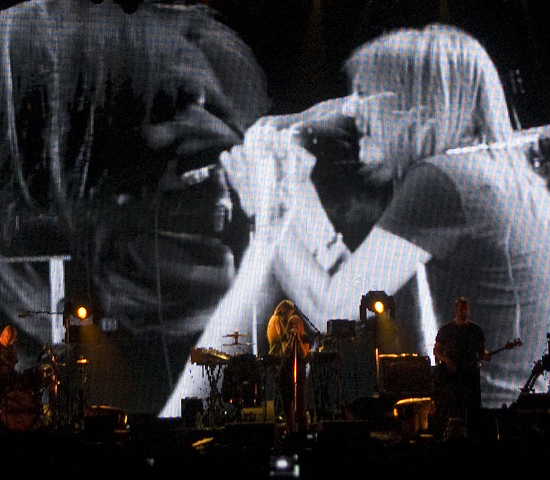

Beth Gibbons is the owner of a voice that is intensely emotional and expressive, yet wholly of this earth: the sound of fear, lost love, broken promises but unbroken desire. When twinned with the industrial paranoia of ‘Machine Gun’, say, or the hopeless hopefulness of ‘The Rip’, the atmosphere is at its heaviest. As if to accentuate the hypertension that much of Portishead’s material instils in you (particularly from Third), the organisers have installed a massage zone at the back of the hall. It cuts a surreal sight: while bleak electronics hammer out, fans are massaged in a line while searchlights swirl over them. Psychodramatic as ever, then, an interior world explored with the nuanced touch of a band that knows what it is it does. Their sluggish approach to releasing records betrays a group of musicians who painstakingly pore over every detail, terrified that they might make a wrong move – or a false start, as they do with their newest song, the two-year-old OMD-like ‘Chase The Tear’, which they struggle with on both nights – on the second they give up trying after a few attempts.

At the side of the grand hall Company Flow’s El-P poses for photographs. Phones are clutched as fans take pictures of friends to post later. Fair enough, particularly after a set that reaffirmed Co-Flow’s power. After a prolonged technical hitch that delayed proceedings by over half an hour, El-P and fellow rapper Bigg Jus joined the unflappable mixmaster Mr. Len on stage and immediately injected the day with the spark it needed. El-P hurling himself around the stage into the air, and Bigg Jus affecting his twitchy, woodpecker flow. One of the weirdest bits of trivia to go viral during the recent phone hacking scandal has been James Murdoch’s early funding of Rawkus Records. El-P repaid James’s now-distant act of benevolence with a message: “James Murdoch – in your darkest hour when you are cry-sterbating [work it out] alone, remember that, despite the fact you sank Daddy’s kingdom, Company Flow is still here. Thank you James!” They launch into ‘Patriotism’, a song with lyrics that could have been inserted as captions underneath pictures of the Murdoch show trial (“I’m the ugliest version of passed down toxic capitalist”), before refusing to leave the stage after breaking their curfew.

Later in the same West Hall, Factory Floor continues the long march toward mass appeal with a crucial breakthrough – a room full of people dancing. Is it because many in attendance are out-of-towners, unaffected by the self-consciousness that usually cloaks London events? Or is it because this is a band that is taking part in a process of trial and error, of honing its craft, figuring out which audience buttons to press. This was their finest display so far in a year that has constituted an entirely upward curve: one highlight was ‘Lying’, their “hit”, which built up and up, taking it to giddy, intense, mesmeric heights.

After oversleeping robs us of attending the (from overheard accounts an apparently brilliant) two hour Godspeed You! Black Emperor set, it is the live-soundtracked showing of Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc in the West Hall that kicks Sunday off. Portishead’s Adrian Utley, on the far left of a line of guitars, joins a small choir, harp, brass, percussion and conductor Charles Hazlewood. It is not every day that you find yourself and others dancing to the bit where the monk condemns Joan to the torture chamber, but such was this score’s effect. Militaristic beats, horns of mild alert, soaring soprano, and creeping, insidious guitar all contributing. Yet none could come close to the power of Dreyer’s close-ups.

Anika channels the voice from the singer of this festival’s title-track “I’ll Be Your Mirror”, Nico. Her Germanic inflections are pinched from Berlin instead of Bavaria and imbued with a Bristolian sense of chalice-fuelled protest, over understated ESG beats and icy, end-of-the-world attrition.

Next door the Great Hall is doing its best to mute the badass loudness of Swans, my current Best Rock Band on the Planet – but it’s failing: it can’t stand up to Mad Michael Gira and his travelling band. No one can at the moment. People were muttering afterwards that Grinderman played the best set of the weekend but that’s not true because, while Cave at the moment seems as animated, engaging and loose as he’s been for years, you can imagine him not being in Grinderman. Doing something else, with the Bad Seeds or maybe writing another book or just being, you know, Nick Cave. But when you watch Gira spitting booze over himself in a rage, or his bandmate Thor Harris, an indomitable percussive force, you can’t imagine them doing anything else. It might all be an illusion, but it’s a fantastic one.

The writer /occultist/pop historian Alan Moore and Sunn O)))’s Stephen O’Malley had an interplay, a respect, that was as intriguing as Harry Smith’s film collage that played behind them both, taking it in turns to be the dominating accompaniment to the animation. Moore – stood at a lectern in a sparkling coat, with hair pulled back (functional) – eases us through Smith’s bountiful life story, a story of the 20th century. “As fascism swept Europe he was horny,” he describes of Smith’s teenage years, before adding the inspired summation: “Hiroshima: a global tinnitus.” O’Malley intermittently adds carefully crafted rushes of distortion and feedback. Behind them both a black and white skeleton spikes a watermelon with a complex contraption, dancing in a weird void that seems like a Jungian factory. After a while you feel Moore is describing himself, as much as Smith. "He doesn’t weaken, the work is too important… There’s just too much to him…all wild and staring."

All that is left is to retreat to the cinema and catch Peter Whitehead’s genuinely enlightening documentary, Tonite Let’s All Make Love In London. Presumably included on the bill as it includes footage of the 14 Hour Technicolour Dream, the UFO/IT gig that happened here in April 1967. It is an event that has in hindsight been heralded as the starting pistol which helped kick off the original “Summer of Love”: the point where rock music culture accelerated, eventually providing the context for today’s audience which has yet to have had a name tagged on to its own head-spinning summer.

Like all good culture, the best of what happened here seemed like an extended critique – a critique of communication in the birthplace of television, curated by a group of musicians, (and therefore communicators of a sort) who know only too well the perils of the media swamp. It’s difficult to know what you are supposed to expect from artists as a response at times like these, with news travelling so fast it’s running away from itself. But, on reflection, it did feel like a mirror of sorts.