For anyone of a certain age who studied French at school, the western port town La Rochelle will always be indissolubly linked with the Tricolore textbooks (and characters including a mentally disturbed bag lady called Fifi Folle and a tramp called Claude). It’s also where I had my first experience of oysters (had a dozen in one go, felt a bit giddy afterwards and ended up splashing out on a French sailor top), and is home to the Les Francofolies de La Rochelle festival, now in its 27th year and running from 12th to 16th July.

It’s a pretty wholesome, family orientated event, and one with a particular focus and musical slant. It’s devoted to French and Francophone acts, and leans heavily towards variété – mainstream, middle of the road artists with cross-generational appeal – and chanson-derived pop. That didn’t prevent it from sliding into controversial territory two years ago, the last time I was here, by booking then dropping Orelsan – a kind of French Mike Skinner – who had released a song called ‘Sale Pute’ (‘Dirty Whore’). In the song, Orelsan catches his girlfriend in the act with someone else, and proceeds to give a vivid and at times gynaecologically detailed account of how he feels like treating her as a result (and how he feels generally about certain types of women, including Paris Hilton).

The debate extended beyond just the Francofolies, with many, including presidential candidate and president of the regional council Ségolène Royal – who, as it happens, was on a PR walkabout this year and walked right past me one afternoon while I was having a quiet moment in the sun – attempting to earn a little easy political capital by making their feelings on the rapper known. Meanwhile, echoing the public mood, many artists leapt to Orelsan’s defence, including sock-faced singer-songwriter Cali, who announced that he would be boycotting the festival in future.

Something similar could conceivably have arisen in England as well but the fact it was here gave it a specific charge; Les Francofolies isn’t a rock festival, it’s about French culture, cultural heritage and chanson, in which words, French words, have a status above all else. The biggest story this year is the fact that on 14th July (Bastille Day, officially La Fête Nationale) all the acts appearing on the largest stage, which is set outdoors on the Saint-Jean D’Acre esplanade, are groups that sing in English. The next day, regional paper Sud Ouest reports it as a successful experiment: "Although criticisms were aired about the totally Anglophone line-up yesterday… audience members of all generations gave their seal of approval to a bill entirely in the language of Shakespeare on an evening of national celebration."

Inside the main indoor venue, La Coursive, there’s an exhibition of record sleeves and ephemera devoted to singing/songwriting legends like Serge Gainsbourg, Charles Trénet, Yves Montand, George Brassens and Gilbert Becaud, called Les Voix de Nos Maîtres (‘Our Masters’ Voices’). Many of the sleeves are delightful but it seems too obvious, too easy – these people are never not being celebrated in France. (Also, what about Nos Maîtresses – was there no room for Barbara, Juliette Gréco or Françoise Hardy? Maybe that has already been planned for next year.) The weight of these masters (and mistresses), of their omnipresence, can be felt keenly by younger musicians. Many choose to write in English partly because it’s the language of the (rock) music they love but also because in French they’re always going to be (or at least feel as though they’re being) judged by the poetic standards of icons like Brassens, Brel, Ferré or Gainsbourg.

Others have a go at measuring up to those standards, and singing in French brings other rewards – it promises more radio play (those famous 40% French language radio quotas), French labels know how to market it, and there is a cultural cachet attached. A singer-songwriter called L plays in La Coursive a matter of days after winning le Prix Barbara, a prize inaugurated by Frédéric Mitterrand (nephew of François) for young singer-songwriters.

In chanson it’s usually a question of having musical ‘settings’ for the lyrics, which are often melancholy, minor-chord-y compositions, with classical instrumentation – strings, piano, maybe acoustic guitar. There will be twists – L is one of the more traditionalist chanteuses; Élodie Frégé, who was the winner of Star Academy (the French equivalent to The X Factor) in 2004 adds vaguely ‘contemporary’ beats and represents a more pop-orientated approach that merges with variété. Actresses are constantly getting in on the game as well, behaviour that the French have a pretty high tolerance for. Here, Mélanie Laurent (Inglourious Basterds, Beginners) seems to be taking it seriously enough and the audience give her the benefit of the doubt.

In the hotel every night after watching the live shows I switch on a channel playing music videos – the selection that’s on in the early hours is called Tendances (‘Trends’) and it’s full of winsome, wordy pop. There is sometimes a staccato ‘Penny Lane’ rhythm to make things a little more upbeat or, if the artist wants to demonstrate a little daring, there might be some light, non-committal disco guitar of the kind Florent Marchet (also at the festival) goes for. This is the legacy of chanson too, in the way that it often feels as though the music is just a prop. I wonder if it would be possible to to even start the Retromania debate in France, so strong is the sense of continuity, of maintaining a certain conception of the ‘song’.

On the subject of Retromania, Simon Reynolds makes Japan the paradigm of the "pastiche/recombinant" ethos, but before that on his blog he’d already suggested that maybe "we are all French today", talking about the "twice-removed, distanced aura" of some of the country’s rock output. (There are clearly affinities between the countries on that count, as mentioned in May’s Rockfort column on Tricatel Records.) There are several striking exemplars of this sensibility at Les Francofolies.

Twin Twin are like a post nu-rave Village People:

Brigitte are a highly stylised act, two girls (one blonde bombe and one a Daria-like ‘geek’), and their songs often seem like they are intended to be like a teenage girl’s diary blown up to cartoonesque proportions. Of course it’s a bit ‘edgy’ (see the video below) but it’s definitely right within variété, just oft-centre enough, and the music is a patchwork of pastiche.

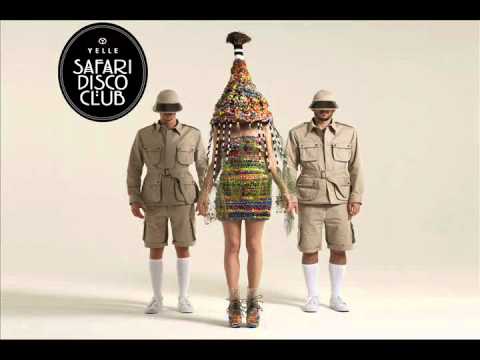

Yelle, who have been touring with Katy Perry, fit the bill as well, but I’m generally more partial to their neo-neo-Yé-Yé (for neo- Yé-Yé, see Ellie et Jacno and Lio’s hits like ‘Banana Split’ and ‘Amoureux Solitaires’) particularly because there’s sometimes a melancholy tinge to the music of singer Julie Budet and producers Tepr and GrandMarnier, perhaps because they’re older than the girls of Brigitte. On ‘Comme Un Enfant’ she sings about being "like a child… like a teenager" which she clearly isn’t any more, however many dressing up games (their second album is called Safari Disco Club) she plays.

But the undisputed king of deuxième degré (ironic distance) is Philippe Katerine (or just Katerine) who, on the evidence of his performance here, has completed his transformation from arch pop aesthete…

… into some kind of holy fool. At least that’s the kindest interpretation:

His most recent album (and there’s a version in English too) consists almost entirely of songs like the above, a literal reductio ad absurdam of his style. I guess the idea is that this rather Jarry-esque revelling in/satirisation of bêtise (commonplace stupidity and banality) should be liberating – plenty of people in the audience clearly respond to these songs in that way – but it doesn’t work for me. There’s too much conceptual and musical laziness masquerading as off-the-cuff, cosmic un-profundity (of course, that’s just my blah blah blah). He does hit some kind of mark a couple of times though, once with ‘Marine Le Pen’, a song in which he winds up being stalked by the current president of the Front National (the French BNP), and again when he vocally replicates a sample of the Windows XP shut-down sound, "deee-da-doo-dan", repeatedly, while the band glide into velvety soul mode. It all goes smoothly for a while until his delivery starts to become decidedly unhinged.

(There’s also some thoroughly non-ironic pop on offer, the worst of which is a show from Nolwenn, another Star Academy alumnus, who has been getting back to her Breton roots recently. The show is a Celtic mish-mash combining ersatz Breton folk stylings with covers of ‘Dirty Old Town’, ‘Whiskey in the Jar’ and, jeez, ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’.)

In terms of musical hybridity, the finest exponents are hyper-eclectic Franco-Finnish duo The Dø (augmented by a full band) who are a blessed relief on the ‘English language-only’ bill after the cute but dull Cocoon and grunge-y nightmares Yodelice. At its best (ie when they’re not doing their more cutesy indie-guitar tunes) their kaleidoscopic art rock recalls The Sugarcubes, and it’s undoubtedly the most challenging set the main stage crowd witness all week, with any sweetness leavened by scabrous, ring-modulated peals of guitar and skronky sax. They haven’t really caught on in the UK but they’re big in France now, which is good – the French mainstream needs them.

Les Francofolies does throw up some alternatives to pick n mix and detachment as well. In the absence of any future chasing, a couple of artists appeal to me for their musical integrity, their singularity of purpose. Psykick Lyrikah from Rennes, based around rapper Arm, don’t demonstrate any interest in what the state of contemporary rap might, or should, be but neither are they an obvious throwback to any ‘golden age’ (for that, see a rising Parisian group called… really… 1995). Arm’s band, guitarist Oliver Mellano (one of the nicest and hardest working men in French music) and DJ/bassist/sampler-operator Robert Le Magnifique, deliver an imposing, near-industrial backing for Arm to ride in a pensive manner. There are no fireworks, just a sustained, focused intensity. The audiences here are used to artists cheerfully playing up to them and this proves to be too alienating for some, who leave the auditorium. Others who stay I think, like me, find it a rather salutary experience.

The other case is Bertrand Belin, whose most recent album, Hypernuit, was praised as a masterpiece is some (French) quarters. I didn’t get it – this Americana-tinged chanson seemed well-crafted enough but somewhat same-y. Live, though, it’s that same sameyness, the subtle variations on it, that helps to cast the spell, thanks to the deftness of his band (and his own guitar playing) that allows for delicate flourishes and subtle shifts into abstraction. When he plays an earlier song, ‘Porto’ I also get a sense of why Hypernuit was so well received by French critics – ‘Porto’ is fairly standard-issue chanson-pop whereas the new songs demonstrate a richer musicality as well as a more stripped down, essentialist lyrical approach. This must have felt like something to celebrate.

The Chantier des Francos (literally the ‘construction site’ of Les Francofolies) is the source of several festival highlights. The idea behind the Chantier is to take a group of bands/artists on tour, as well as helping them to develop stage craft, vocal techniques, interview technique and so on. As a Brit, I’m torn between suspicion of this approach (how prescriptive is the coaching? Where’s the DIY spirit?) and admiration (France supports its artists!). Given the acts selected, there’s good reason to view it positively.

Frànçois and the Atlas Mountains (yes, French scholars, there is an odd accent on Frànçois’s name) are the first French signings to Domino. After some line-up changes, these pleasant folkies have mutated into a more buoyant, dance-oriented proposition, with chanted refrains and Afro percussion sometimes taking them into Animal Collective-lite territory. There are also the beginnings of some stage choreography and Frànçois dances like Sting did in the Police – I’m not sure whether that’s down to the Chantier or not.

Tours-based Mesparrow (aka Marion Gaume) one of the founders of the Decorative Stamp collective when she lived in London, is also producing some dreamy vocal loop-based pop which in the wrong hands could end up being overly prettified but with the right producer… well, we’ll see. I think she knows what she’s doing.

And La Féline are charming. Singer Agnès has also provided some haunting vocals on the latest Mondkopf album, Rising Doom, and her band have been tentatively staking out a space where Morricone, Night of the Hunter-esque Southern Gothic, Greek myths and the elegiac 80s synth pop combine (I know I’m mixing up visual, literary and musical references – they’re that kind of band). What I like most about La Féline at the moment is that they don’t feel settled yet; there’s an undercurrent of restless desire – they’re still casting around, occasionally overreaching – and it’s rather moving if you’re receptive to it.

The Casino Barrière, which is a 15-minute walk along the beach from the main stage, aims to draw a younger/hipper crowd, so you get DJs like Brodinski and Lauphi knocking out the electro tunes as well as live bands. The Shoes, who count Mike Skinner among their fans, are OK if ultimately rather blank, their Balearic-meets-Glitter beat (multiple live drummers are deployed) squarely targeted at at East London. Bewitched Hands have been talked up in France as a band to follow in Phoenix’s footsteps and break America (check this video, they’re definitely aiming for it).

I couldn’t square that at all with unremarkable recorded evidence and I’m still not a fan, but live their slacker rock does have a surprising heft and there is an Arcade Fire-like sense of togetherness and communal endeavour. At least they’re all pulling in the same direction, which is not quite the case for Le Prince Miiaou. That’s a shame because, in the two years since I last saw her at this festival, Maud-Élisa Mandeau (she’s the singer-songwriter, it’s her baby) has gone from affectingly timid to ultra-assured frontwoman. She’s got some harder-rocking and more anthemic material and she carries the show, superbly, through force of personality but a sharper band is needed.

Saturday, the last day of the festival – the previously glorious weather turns to shit and the heavens unleash hell. It’s because David Guetta is coming, I decide.

Actually, the worst downpour is during the Katerine set; David commands the elements with the same ease he displays when working a crowd. His techniques are simple but devastating – like turning the whole track right down so the crowd can hear themselves singing. Not the vocals, the whole thing. About five times per track. Then he stops everything and gets people to scream when he plays a single kick, "so loud even extra-terrestrials on the moon can hear you!" This is real God is DJ stuff (or God Is a Jet-Setting Super Goon). He’s wearing his ‘F*** Me, I’m Famous’ T-Shirt. At one point, Martin Solveig, who’d be on earlier in the evening, runs on stage to embrace him then scampers off again. Some of the music is pretty exciting – it can’t not be, it’s so loud, there are so many people here going mental for it, and David hasn’t got to where he is without learning a thing or two about dance music dynamics. He finishes by playing Black Eyed Peas’ ‘I Gotta Feeling’, which underlines the part he’s played in the Euro-fication of R&B-pop. I’m not saying he’s entirely responsible but he is the European guy who’s infiltrated the US with this stuff and worked with BEP, Flo Rida, Kelly Rowland, Akon, Kid Cudi, Rihanna, Kelis. David Guetta is, undoubtedly, about as plugged into the pop now as any man can be.

For more from Rockfort, you can visit the official site here and follow them on Twitter here. To get in touch with them, email info@rockfort.info.