For millions of people, June 16th is an important day. On this day, 107 years ago in 1904, two residents of Dublin, Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom, embarked on their epic converging journeys through the city, as depicted by James Joyce in Ulysses. Over the last thirty years or so on this day, celebrants of the book act out various scenes in cities and towns all over the world, displaying their willingness to be at one with the novel. But the question is: how many people have actually read this famously difficult text? The answer is probably not very many; this book which strove to celebrate the everyday life of the common man and woman has endured the unkind fate of never being read by most of them.

While the book itself may simply be too much for the everyday reader, this did not render the novel entirely unfilmable. In fact, it took Joseph Strick, an idealistic American, to fully realise its cinematic potential. After years of frustration, Strick managed to film the first and definitive version of Joyce on screen with his 1967 adaptation of Ulysses. Strick died last year without ever seeing requisite acclaim afforded on his achievement. Indeed, the film caused great controversy at the time of its release. A significant number of subtitles were cut during its screening at the Cannes Film Festival, which Strick later dismissed as "corrupt and fake, and just a mechanism for keeping the hotels open". The British Board of Film Censors forced 29 cuts, but eventually passed the film – it became the first in Britain to include the word ‘fuck’ – after Strick re-submitted it with the ‘offending’ sequences replaced by a blank screen and a shrieking soundtrack. In Ireland, the film censor unilaterally banned the film, denouncing it as being "subversive to public morality". It wasn’t until 2000, a year after the Irish censor belatedly passed Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange for release, that Ulysses was finally given the go-ahead for public consumption.

It is ironic that the film version suffered so many obstacles, considering the fact that Joyce, in depicting the flaneur-like ramblings of Leopold Bloom in the novel, deployed a whole range of techniques such as montage and rapid scene dissolves which are more commonly associated with the cinema. Joyce was clearly a fan of the cinema as well, having opened the Volta, one of Ireland’s first dedicated cinemas in Mary Street, Dublin in 1909.

Ulysses is a novel so rooted in a sense of place that, as its author once memorably put it, if Dublin was to "suddenly disappear from the Earth it could be reconstructed out of my book". The decision by Strick to base his adaptation in 1960s Dublin rather than the novel’s original setting of 1904 ensures that the mise-en-scene does not take away from the film text and in fact serves to highlight the contemporaneity of Joyce. If anything, this juxtaposition of past and present affords the film a unique timelessness.

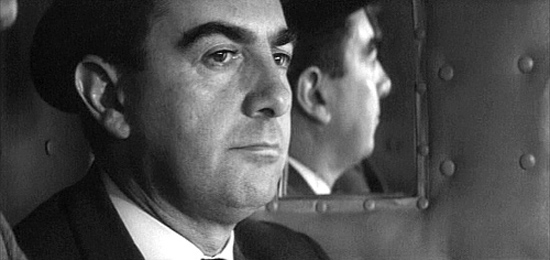

Milo O’Shea excels as Leopold Bloom, the clever and libidinous protagonist, his external dialogue wonderfully evoking his surreal and spiralling fantasties, anchored with a vigorous undercurrent of shocking-for-its-time sexuality. But the real star of the film is Dublin itself; the black-and-white cinematography ensures the city’s aesthetic dimension becomes a prominent character with O’Connell Street, the Ha’penny Bridge and Glasnevin Cemetery serving as iconic visual adornments without falsifying the city’s burgeoning modernity.

Up to this point, Dublin city had been primarily represented by theatre, in the early twentieth century, via the successes of playwrights Sean O’Casey and J.M. Synge. With the advent of cinema and modernity, adaptations of literary heavyweights rarely, if ever, used Dublin itself as a backdrop as studios preferred the more sanitised, cardboard sets offered by Hollywood (which often were accompanied by unintended laughs through wildly inaccurate imitations of Dublin accents and incredibly naïve captions).

Joyce’s attempt to plan out the winding topography of Dublin city is perfectly realised during Leopold Bloom’s carriage ride from the south to the north of the city. Strick offers us a unique depiction of industrial Dublin as the cavalcade travels its way through the Grand Canal and winding city streets in the 1960s. Film critic Bosley Crowther commented upon the city’s modernity during this passage, noting that "the streets are full of automobiles. The quays along the river are crowded with modern ships."

Since Joseph Strick’s attempt, film versions of Ulysses have been few and far between. Sean Walsh’s 2003 effort, Bloom, is an altogether more mundane effort, with Stephen Rea as a far more taciturn Leopold Bloom. In contrast, Strick managed to successfully capture the humour and pathos while adhering to the wonderful directions outlined within the novel. It is testament to his direction that the juxtaposition of such a series of seemingly unrelated events seems effortless as the camera work glides from one fantasy to another, straddling the boundaries between humour and horror.

Joyce’s tale concerning one day in the life of a Dubliner was never meant to be for elite readers only. Joseph Strick’s film version manages to neatly sidestep all the theoretical babble and allows viewers to enjoy a wonderfully rich story. The film sheds light on an otherwise daunting read and conveys a humane vision of a decent life under the encroaching pressures of the modern world.