"I warn you, I’m drinking wine," confides Erika M. Anderson – the former voice of LA noise merchants Gowns, who contemplated quitting the music business completely before throwing herself into a solo venture under the moniker of EMA. Resigned to moving back to South Dakota to become a teacher or a waitress, a chance call from Krista Schmidt from Souterrain Transmissions prompted her to give it one more chance; the result is Past Life Martyred Saints, one of the finest LPs of the year so far. It takes in bruised, disturbing confessionals (‘Marked’, with its unsettling lyric of "I wish that every time he touched me/ Left a mark") and, as John Doran rightfully noted, expands her lo-fi horizons with tracks such as ‘Breakfast’ and ‘Anteroom’. And that’s all without mentioning ‘Kind Heart’, one of the most jaw-dropping tracks of 2011, even if it didn’t find a way onto the LP: an ever-shifting 17-minute interpretation of Robert Johnson’s ‘Kind Hearted Woman’, that flits between brittle heartbreak and howling chaos throughout its lengthy duration.

"OK, can we take two seconds and can I ease into it?" says Anderson when we attempt a question. "Let’s have a slight conversation before we get into an interview. I thought I should figure something out about you before we spoke, so I Goolged you and the first thing that came up was some goat farmer from Vermont."

Yeah, that’s not me.

Erika M. Anderson: I was really confused for a second.

Are you disappointed I’m not a goat farmer?

EMA: [Laughs] No. I don’t know if they filter through country, so they just show the US results…

Let’s go with that theory, because it’s probably better for my ego.

EMA: Yeah, let’s say that. And then I found you, and saw you’d talked to some cool people recently, so I thought I’d drink some terrible wine.

Why?

EMA: Because I get nervous about interviews. And there’s a full moon out there, which really makes me want to get wild. I don’t know if it’s because I’m a farmer’s daughter, but I can feel it, so I thought this person in England who is drinking coffee can be my wild, full moon partner.

How did you start working as EMA?

EMA: Well, my last band had basically imploded at that point in time, and there were still a lot of songs that I really cared about, and that I still wanted to work on. But actually, before that transition was made, I was tired of music. I thought, ‘This has broken my heart too many times, so I’m going to move back into my parent’s basement in South Dakota, and get some normal job and drink a lot of beer’.

Were your parents happy about that?

EMA: They were actually excited, because they missed me and thought that I would cook for them if I moved back home – like, ‘You know all these healthy California recipes’. They always want me to come back to the Midwest; people from the Midwest don’t ever want to leave there.

So how did Gowns implode? Did it come to a messy end?

EMA: It was strange, because I think we probably should have broken up long before we did. I think some ways, we had spiritually broken up before we officially did. It was crazy; both me and Ezra [Buchla]… it was almost like a game of bluffing, looking at each other and saying ‘Are you going to keep going? OK, I’ll keep going’, even after it was obvious that it was an absolutely insane endeavour. I think we did both care about the music and thought it was something special, and the one thing I’ll say about Ezra is the he’s always believed in me. He was like, ‘I want to get your music out into the world, I want to support you’. But we couldn’t work together on any emotional level that was sane.

Do you feel you have more freedom with what you do now?

EMA: Yeah, I do. The one thing about working with Ezra was that… he was this weird, curmudgeonly fellow. You had to ask him something a million times before he’d tell you; he wouldn’t talk until he was ready to talk. But he always had the best advice.

But also, I did feel like some of the crazier songs, or some of the weirder songs I’d been wanting to write… I felt like I couldn’t say the things I wanted to say. I felt weird representing him and putting out a really strong statement that had his name on. A Gowns record came out and there was a lot of talk about drugs on it, a lot of which came from talking to people I’d know growing up. But people were lazy, so they’d infer things – ‘They’re on drugs all the time’ – and I remember Ezra saying ‘I’m a little bummed out that The Wire thinks I’m a junkie’. The things I want to say can be kind of extreme, so in that sense, I do feel that I don’t have the same pressure. Whatever I say is going to be on me, and not on him, so I feel more free to say what I want to say. I don’t have anyone telling me ‘You might not want to say that, because it’s a bad idea’.

Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

EMA: [Laughs] I don’t know. I guess we’ll have to see.

Why did you decide to leave the Midwest for LA?

EMA: It was kind of a naive choice, in many ways. I really liked the song ‘Welcome To The Jungle’…

By Guns N’ Roses?

EMA: Yeah.

But… that song made you want to move to LA? That song wouldn’t want me to move to LA.

EMA: Yeah, I don’t know… when you’re in the middle of nowhere, you don’t have any idea of what you’re going to like. You just throw darts at it. And LA’s always had a lot of media, so you feel familiar with it.

Is ‘Welcome To The Jungle’ actually like LA? I’ve been there – admittedly only for a couple of days – but I didn’t see too many similarities.

EMA: [Laughs] No, I don’t think so.

So let’s talk about the album. How would you describe it? Because for me, the most striking thing is its diversity…

EMA: Yeah, there’s a lot of different sorts of… it depends who I’m describing it to.

In what way?

EMA: Well, if someone asked me in a bar or something, I’d just say ‘You know, it’s just rock music’.

You don’t have to dumb it down for us…

EMA: You’re right, we’re not relatives in a bar. I think it’s really diverse, and it takes a general love of music and puts it through my own filter; there’s so many genres I love… I’d love to do more hip hop songs, and ‘California’ is the closest I’ve got to that. I love playing with the signature of things. I’ll listen to an 80s song and think, ‘Wow, listen to those drums – I’m going to steal that’. It’s also important to me to be more honest than I should be.

In what way?

EMA: Well, it’s scary to let people know certain things about you, with songs like ‘Marked’ or ‘California’.

You seem to play with traditional structure a lot – there’s not a whole lot of verse/chorus/verse songs to be found on the album, and you often change fidelity mid-song…

EMA: Yeah, it’s weird – even though I listen to pop music and the cheesiest classic rock, I never naturally write a verse/chorus/verse song. ‘Milkman’ is probably the closest I’ve come. I mean, I like it when I hear the chorus come back in, or when it repeats, but it doesn’t come naturally to me.

You mentioned ‘California’ being like a hip hop song – you have a go at rapping, I guess.

EMA: What?

Rapping.

EMA: Like… rasping?

No, rapping.

EMA: Oh, yeah. I think the phone line cut out…

Maybe it’s the wine…

EMA: [Laughs] Oh, come on now. But yeah, growing up in the Midwest, I felt there was certain types of music that I couldn’t really hear, and one of them was hip hop. I could listen to the best people, but it didn’t sink into my brain at all. The only time it started making sense was when I was in West Oakland, and then it came out of every store, and every apartment. You’d walk around and there’d be a constant bass throb, and it started to make sense to me.

I guess that there might be rules, and that as a white girl from the Midwest I can’t do a hip hop song. But I tried.

Did you feel self-conscious doing it?

EMA: I think a lot of the best art you can make, and a lot of the coolest things that are ground-breaking, you do feel self-conscious when you make it. It’s a big challenge, wanting to pull that off, and I guess I kind of get off on that challenge. How do you interpret the song? And how can you remain true to the song?

But then, people listen to it and don’t get that at all. It’s like, ‘OK! This is my rap song, I’m going to rap!’ And they’re just like, ‘No. Fail’.

We were talking about you being too honest, and there does seem to be a violent aspect to the album – with songs like ‘Marked’, as you said. And I heard ‘Butterfly Knife’ was inspired by a teenage goth killing in LA…

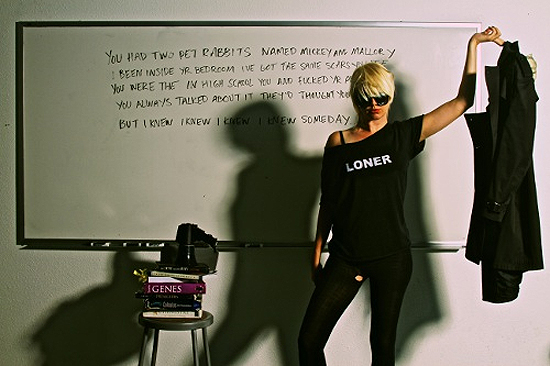

EMA: I read this story that was in the LA Weekly a few years ago, about this teenage goth couple in Redlands, California, who murdered their friends, or one of their ex-friends or something, and a couple of details from the story stuck with me. They were so kind of trashy and tragic. Like, one of them had a set of rats and they were named Mickey and Mallory, from Natural Born Killers. Something about it stuck with me. And I was a weirdo at school – I was rebellious, and had a shaved head, and went over to my friend’s house to smoke pot and watch Natural Born Killers. It’s like Columbine – being a young teenager and growing up in a place where a lot of people had access to guns and being angry, I remember there almost being talk about it. Like, people would joke about bringing in guns and taking over the school assembly. It was in the air. It was in the water, in the American dream at the time. So when it did happen, I wasn’t that surprised.

I guess that in the UK, one of the most alien things about that was realising just how accessible guns were to teenagers, and I suppose in certain parts of America, that’s not surprising at all.

EMA: Yeah. A lot of people I went to high school with, their parents hunted, you know? I mean, my Dad’s a conservationist so he’s no redneck hunter, but when I was 14 he wanted me to take Gun Safety class. So I was a 14-year-old with a shaved head and big combat boots in Gun Safety…

You sound pretty scary.

EMA: [Laughs] I wasn’t even the scariest one there. There was this lady who kept going on about ‘the mark of the beast on your hand’, and she kept saying we had to get guns because all this ‘stuff’ is coming. So she was the scary one.

What about ‘Marked?’

EMA: That’s a tricky one to figure out to succinctly explain.

Because it’s hard to talk about?

EMA: It’s just that… I’m still trying to figure it out for myself, really. It’s actually very old, and was written in one take. And I won’t comment on my sobriety at the time, but there was no planning or notebook or anything; the take you hear on the record is the take of it being written. People really connect to that song. It’s been around for a while, and people ask me ‘When is ‘Marked’ coming out’? So I’ve been thinking about the day when I’m going to have to explain what this song is about.

The one thing I will say about it is that I don’t want it to be a romanticised look at domestic violence. There are lots of forms of violence, I think, and not all of them leave marks.

Well, one of the things I got from the song was that it’s not necessarily literal – that some things don’t have to be physically violent to hurt, and they can leave something deeper than a physical mark.

EMA: Yeah, definitely. I definitely don’t want it to be taken at a face value that’s the same as, you know, ‘He Hit Me (And It Felt Like A Kiss)’.

I wanted to ask you about ‘Kind Heart’, which is one of my favourite songs of the year. How hard was that to do?

EMA: Oh my God, it was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. It was awful. I can’t even listen to it – I never want to do that again. I was like ‘I’ve wasted my life, this song is cursed, I hate this’. I just think of struggling indie filmmakers who are trying to do a crane song – the whole thing is like a fucking crane shot. It’s 17 minutes. I felt that it was too ambitious – ‘Why the fuck did I do this’? It took so much out of me, especially with no support. It would be one thing if someone – I don’t know who the fuck who – had said ‘I’m going to commission you to make a 17 minute version of ‘Kind Hearted Woman’’, but it was just something that I felt passionate about.

I wanted to have all these movements in it, I want it to dissolve into chaos, I want it to have feedback, I want to get all the harmonies right. And it just felt like a mad pursuit. It was like trying to push a boulder up the mountain.